Omar Farahat at Brill:

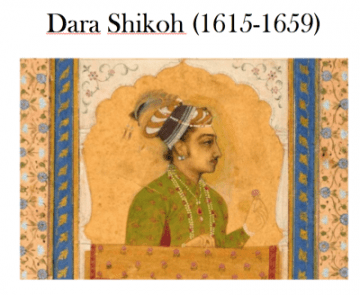

Khurram Hussain’s Islam as Critique: Sayyid Ahmad Khan and the Challenge of Modernity is an important and highly original book. At one level, the book is a fresh reading of some of Sayyid Aḥmad Khān’s (d. 1898) most profound intellectual contributions. At another, more important (at least for this reader) level, the book is an elaborate set of reflections on the place of Islam in the West and the place of (the study of) Islamic thought in modernity. The book’s offerings are daring and original, and the style is engaging. There are, inevitably, given the ambition of the project’s claims and the size of the book, areas in which one wishes the book offered a fuller discussion. Similarly, given the bold and very timely nature of the arguments, there are many venues that call for engagement to which we can and should respond. Thus, the book is obvious interest to scholars of South Asian Islam, Islamic thought, and broadly anyone concerned with the crises of modernity and alternative ways of being in the world, which, ideally, should be everyone.

Khurram Hussain’s Islam as Critique: Sayyid Ahmad Khan and the Challenge of Modernity is an important and highly original book. At one level, the book is a fresh reading of some of Sayyid Aḥmad Khān’s (d. 1898) most profound intellectual contributions. At another, more important (at least for this reader) level, the book is an elaborate set of reflections on the place of Islam in the West and the place of (the study of) Islamic thought in modernity. The book’s offerings are daring and original, and the style is engaging. There are, inevitably, given the ambition of the project’s claims and the size of the book, areas in which one wishes the book offered a fuller discussion. Similarly, given the bold and very timely nature of the arguments, there are many venues that call for engagement to which we can and should respond. Thus, the book is obvious interest to scholars of South Asian Islam, Islamic thought, and broadly anyone concerned with the crises of modernity and alternative ways of being in the world, which, ideally, should be everyone.

The book advances two primary sets of claims. The first pertains the properly contextualized reading of Khān’s thought as a response to the loss of Muslim sovereignty and identity in the subcontinent following the disastrous events of the mid-nineteenth century. Focusing on one major philosophical question after another, Hussain consistently shows that Khān’s project was an effort to piece together a coherent and viable identity and way of being in the world that systematically eschewed radical or idealized reactions.

More here.

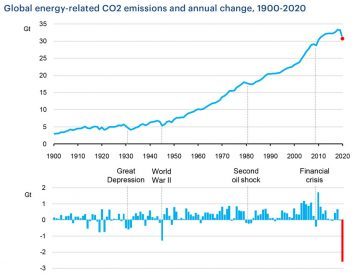

It is perhaps no surprise that such changes in the behavior of human beings, labeled a

It is perhaps no surprise that such changes in the behavior of human beings, labeled a  The long era of European imperialism started in the 15th century but it was roughly 400 years before the land grab turned to Africa. As late as 1870, outsiders controlled only about 10 percent of the continent. But then a confluence of forces opened the door: The need for raw materials, the demand for new markets for finished goods, and medical advances that made it possible for Europeans to survive in the tropics. By the 1880s, the “Scramble for Africa” had begun. At the heart of this rapacious quest was the Congo River in equatorial Africa and its enormous, almost impenetrable, rain forest. Today, this part of Africa includes the Democratic Republic of the Congo, the Republic of the Congo, Gabon, Cameroon, Equatorial Guinea and the Central African Republic. In “Land of Tears: The Exploration and Exploitation of Equatorial Africa,” Yale University Professor Robert Harms deftly and authoritatively recounts the region’s compelling, fascinating, appalling, and tragic history.

The long era of European imperialism started in the 15th century but it was roughly 400 years before the land grab turned to Africa. As late as 1870, outsiders controlled only about 10 percent of the continent. But then a confluence of forces opened the door: The need for raw materials, the demand for new markets for finished goods, and medical advances that made it possible for Europeans to survive in the tropics. By the 1880s, the “Scramble for Africa” had begun. At the heart of this rapacious quest was the Congo River in equatorial Africa and its enormous, almost impenetrable, rain forest. Today, this part of Africa includes the Democratic Republic of the Congo, the Republic of the Congo, Gabon, Cameroon, Equatorial Guinea and the Central African Republic. In “Land of Tears: The Exploration and Exploitation of Equatorial Africa,” Yale University Professor Robert Harms deftly and authoritatively recounts the region’s compelling, fascinating, appalling, and tragic history. Moshe Behar in Contending Modernities:

Moshe Behar in Contending Modernities: Adam Shatz in the LRB:

Adam Shatz in the LRB:

James Brooke-Smith in Aeon:

James Brooke-Smith in Aeon: One person who’s unlikely to fall ill at Donald Trump’s Tulsa rally is Donald Trump. When jubilant supporters peel off their masks and whoop their approval as he torches Joe Biden, rest assured that the president will be a safe distance from any pathogens spat into the air. It’s the crowd that’s at the most risk. Trump’s arrival at the BOK Center on Saturday plunks him into the safest of spaces. Security measures will minimize his exposure to the coronavirus. Adoring crowds will gratify a craving for recognition. Attention paid to his first rally in three months could give his flagging campaign a needed jolt. Tulsa, then, amounts to a salve for a president who needs one.

One person who’s unlikely to fall ill at Donald Trump’s Tulsa rally is Donald Trump. When jubilant supporters peel off their masks and whoop their approval as he torches Joe Biden, rest assured that the president will be a safe distance from any pathogens spat into the air. It’s the crowd that’s at the most risk. Trump’s arrival at the BOK Center on Saturday plunks him into the safest of spaces. Security measures will minimize his exposure to the coronavirus. Adoring crowds will gratify a craving for recognition. Attention paid to his first rally in three months could give his flagging campaign a needed jolt. Tulsa, then, amounts to a salve for a president who needs one. On Memorial Day, the police in Minneapolis killed George Floyd, a 46-year-old black man. Three officers stood by or assisted as a fourth, Derek Chauvin, pressed his knee into Floyd’s neck for more than eight minutes. Floyd said he could not breathe and then became unresponsive. His death has touched off the largest and most sustained round of protests the country has seen since the 1960s, as well as demonstrations around the world. The killing has also prompted renewed calls to address brutality, racial disparities and impunity in American policing — and beyond that, to change the conditions that burden black and Latino communities.

On Memorial Day, the police in Minneapolis killed George Floyd, a 46-year-old black man. Three officers stood by or assisted as a fourth, Derek Chauvin, pressed his knee into Floyd’s neck for more than eight minutes. Floyd said he could not breathe and then became unresponsive. His death has touched off the largest and most sustained round of protests the country has seen since the 1960s, as well as demonstrations around the world. The killing has also prompted renewed calls to address brutality, racial disparities and impunity in American policing — and beyond that, to change the conditions that burden black and Latino communities. T

T Anonymity comes for us all soon enough, but it has encroached with mystifying speed upon the French writer Hervé Guibert, who died at 36 in 1991. His work has been strangely neglected in the Anglophone world, never mind its innovation and historical importance, its breathtaking indiscretion, tenderness and gore. How can an artist so original, so thrillingly indifferent to convention and the tyranny of good taste — let alone one so prescient — remain untranslated and unread?

Anonymity comes for us all soon enough, but it has encroached with mystifying speed upon the French writer Hervé Guibert, who died at 36 in 1991. His work has been strangely neglected in the Anglophone world, never mind its innovation and historical importance, its breathtaking indiscretion, tenderness and gore. How can an artist so original, so thrillingly indifferent to convention and the tyranny of good taste — let alone one so prescient — remain untranslated and unread? For Hegel, the Greek miracle lay in the separating out of mythology and philosophy, so that the articulation of questions about, say, the nature of time, could be addressed in a universal idiom that would not presuppose the existence of Chronos as a divine personification of time. For the ancient Persians, by contrast, to use Hegel’s own example, reflection on the nature of time could only proceed through culturally embedded narratives inseparable from religion and lore.

For Hegel, the Greek miracle lay in the separating out of mythology and philosophy, so that the articulation of questions about, say, the nature of time, could be addressed in a universal idiom that would not presuppose the existence of Chronos as a divine personification of time. For the ancient Persians, by contrast, to use Hegel’s own example, reflection on the nature of time could only proceed through culturally embedded narratives inseparable from religion and lore. Albert Einstein changed our view of the universe in 1915 when he published the general theory of relativity, in which he set forth the notion of a four-dimensional spacetime that warps and curves in response to mass or energy. The geometric foundation for his work was laid some 60 years earlier, with the work of a German mathematician named Georg Friedrich Bernhard Riemann.

Albert Einstein changed our view of the universe in 1915 when he published the general theory of relativity, in which he set forth the notion of a four-dimensional spacetime that warps and curves in response to mass or energy. The geometric foundation for his work was laid some 60 years earlier, with the work of a German mathematician named Georg Friedrich Bernhard Riemann.