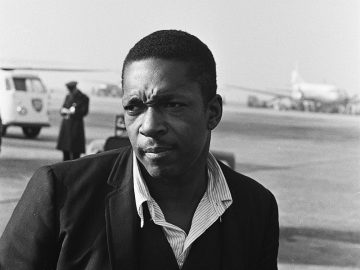

Ismael Muhammad in The Paris Review:

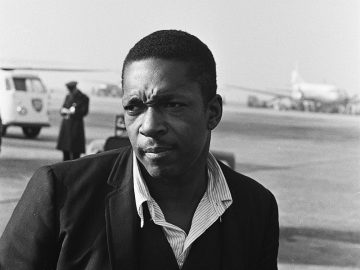

The John Coltrane Quartet’s “Alabama” is a strange song, incongruous with the rest of the album on which it appears. Inserted into Coltrane’s 1964 album Live at Birdland, it’s a studio track that confounds the virtuosic post-bop bliss of the album’s first three tracks, live recordings that include a jittery rendition of Mongo Santamaria’s “Afro Blue.” All of that collapses when we reach the sunken melancholy of “Alabama.” We are far, now, from the cascades of sound that Coltrane introduced us to in “Giant Steps,” far from the sonic innovations and precise phrasing he refined in this album’s live recordings. Here, Coltrane’s saxophone sounds hoarse and enfeebled, until it collapses on the threshold of a hole in the ground.

The John Coltrane Quartet’s “Alabama” is a strange song, incongruous with the rest of the album on which it appears. Inserted into Coltrane’s 1964 album Live at Birdland, it’s a studio track that confounds the virtuosic post-bop bliss of the album’s first three tracks, live recordings that include a jittery rendition of Mongo Santamaria’s “Afro Blue.” All of that collapses when we reach the sunken melancholy of “Alabama.” We are far, now, from the cascades of sound that Coltrane introduced us to in “Giant Steps,” far from the sonic innovations and precise phrasing he refined in this album’s live recordings. Here, Coltrane’s saxophone sounds hoarse and enfeebled, until it collapses on the threshold of a hole in the ground.

In “Alabama,” Coltrane asks us to bear witness to this hole in the ground, which is also a hole in America’s story, which is also a hole in the heart of black Americans. He wants us to grieve alongside him at this absence. The quartet recorded the track in November 1963, two months after the bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama, made an absence of four little black girls. When I listen to Coltrane playing over Tyner’s piano I hear smoke rising up from a smoldering crater, mingling with the voices of the dead. He asks us to peer down into the hole, to toss ourselves over into this absence. Just past the one-minute mark, even this funeral dirge collapses in on itself, as Coltrane’s saxophone sinks into a descending arpeggio, coaxing us in.

…I started listening to and thinking about “Alabama” a lot in the aftermath of Philando Castile’s murder in the summer of 2016, which was reminiscent of the murders of Samuel DuBose, Alton Sterling, Terence Crutcher, Walter Scott, Jamar Clark, Sandra Bland, and countless others. I’d lay down and loop the song through my bedroom speakers because the sonic landscape that Coltrane conjures on the track suggests something about the temporality in which black grief lives, the way that black people are forced to grieve our dead so often that the work of grieving never ends. You don’t even have time to grieve one new absence before the next one arrives. (We hadn’t time to grieve Ahmaud Arbery before we saw the video of Floyd’s murder.) “Alabama” gives this unceasing immersion in grief a form. It’s there in the song’s disconcerting stops and starts, its disarticulated notes, its willingness to abandon virtuosity in favor of a style of playing that is repetitive, diffuse, tentative, and dissonant.

More here.

In The Colonizer and the Colonized (1957) Albert Memmi remarked that “the benevolent colonizer can never attain the good, for his only choice is not between good and evil, but between evil and uneasiness.” Evil and uneasiness are a fair description of the choices faced by Leah Shakdiel, an Israeli peace activist featured in the documentary Can You Hear Me?: Israeli and Palestinian Women Fight for Peace. Born in a house that once belonged to Arabs, she rejected the crusading Zionism of her parents, choosing instead to live in a small town in the Negev desert and to work for social justice. But in order to visit her daughter, who lives in a West Bank settlement, she must travel on what she calls an “apartheid road”—a highway open only to Israelis; her daughter’s decision, Shakdiel confesses to the filmmaker, makes her feel like a failure as a mother. All the same, she loves her daughter. What can she do?

In The Colonizer and the Colonized (1957) Albert Memmi remarked that “the benevolent colonizer can never attain the good, for his only choice is not between good and evil, but between evil and uneasiness.” Evil and uneasiness are a fair description of the choices faced by Leah Shakdiel, an Israeli peace activist featured in the documentary Can You Hear Me?: Israeli and Palestinian Women Fight for Peace. Born in a house that once belonged to Arabs, she rejected the crusading Zionism of her parents, choosing instead to live in a small town in the Negev desert and to work for social justice. But in order to visit her daughter, who lives in a West Bank settlement, she must travel on what she calls an “apartheid road”—a highway open only to Israelis; her daughter’s decision, Shakdiel confesses to the filmmaker, makes her feel like a failure as a mother. All the same, she loves her daughter. What can she do?

What stuck me about “

What stuck me about “ Elizaveta Sivak spent nearly a decade training as a sociologist. Then, in the middle of a research project, she realized that she needed to head back to school.

Elizaveta Sivak spent nearly a decade training as a sociologist. Then, in the middle of a research project, she realized that she needed to head back to school. Two years ago, Chief Justice John Roberts gave the Trump administration a very important piece of advice: When you come to the Supreme Court, you need to do your homework. In his

Two years ago, Chief Justice John Roberts gave the Trump administration a very important piece of advice: When you come to the Supreme Court, you need to do your homework. In his  Once upon a time, education was rhetorical training. Learning to think well, and thereby to negotiate all of life with responsible intelligence, was fundamentally about interacting with—drawing from and contributing to—a fund of powerful writing. But then, to make a long story short, things got complicated, “rhetoric” was demoted to one department among many, and that department was eventually rebranded as “Communication Studies.” In what could serve as a tragic epilogue to the history of Western education, young Mattie, son of the title character in Wendell Berry’s

Once upon a time, education was rhetorical training. Learning to think well, and thereby to negotiate all of life with responsible intelligence, was fundamentally about interacting with—drawing from and contributing to—a fund of powerful writing. But then, to make a long story short, things got complicated, “rhetoric” was demoted to one department among many, and that department was eventually rebranded as “Communication Studies.” In what could serve as a tragic epilogue to the history of Western education, young Mattie, son of the title character in Wendell Berry’s  Steven Levine has written a superb book. The title advertises three perennially puzzling topics: pragmatism, objectivity, and experience. Some background will help locate his project on a larger map.

Steven Levine has written a superb book. The title advertises three perennially puzzling topics: pragmatism, objectivity, and experience. Some background will help locate his project on a larger map. A team of scientists hunting dark matter has recorded suspicious pings coming from a vat of liquid xenon underneath a mountain in Italy. They are not claiming to have discovered dark matter — or anything, for that matter — yet. But these pings, they say, could be tapping out a new view of the universe.

A team of scientists hunting dark matter has recorded suspicious pings coming from a vat of liquid xenon underneath a mountain in Italy. They are not claiming to have discovered dark matter — or anything, for that matter — yet. But these pings, they say, could be tapping out a new view of the universe. Nussbaum concludes that the cosmopolitan tradition “must be revised but need not be rejected.” She proposes that it be replaced by her own version of the “Capability Approach” to development. Conceived by the Nobel laureate economist Amartya Sen as an alternative to the prevailing mode of Western-exported market fundamentalism, the Capability Approach challenges the central tenets of economic globalization in its modern context: free trade, floating exchange rates, capital account and labor market “liberalization,” and so forth. In lieu of a sole focus on GDP and strictly monetary metrics of growth, the Capability Approach advocates a concern with the positive freedoms and opportunities that follow from investments in education, health care, leisure, environmental sustainability, and other factors.

Nussbaum concludes that the cosmopolitan tradition “must be revised but need not be rejected.” She proposes that it be replaced by her own version of the “Capability Approach” to development. Conceived by the Nobel laureate economist Amartya Sen as an alternative to the prevailing mode of Western-exported market fundamentalism, the Capability Approach challenges the central tenets of economic globalization in its modern context: free trade, floating exchange rates, capital account and labor market “liberalization,” and so forth. In lieu of a sole focus on GDP and strictly monetary metrics of growth, the Capability Approach advocates a concern with the positive freedoms and opportunities that follow from investments in education, health care, leisure, environmental sustainability, and other factors. Collective demonizations of prominent cultural figures were an integral part of the Soviet culture of denunciation that pervaded every workplace and apartment building. Perhaps the most famous such episode began on Oct. 23, 1958, when the Nobel committee informed Soviet writer Boris Pasternak that he had been selected for the Nobel Prize in literature—and plunged the writer’s life into hell. Ever since Pasternak’s Doctor Zhivago had been first published the previous year (in Italy, since the writer could not publish it at home) the Communist Party and the Soviet literary establishment had their knives out for him. To the establishment, the Nobel Prize added insult to grave injury.

Collective demonizations of prominent cultural figures were an integral part of the Soviet culture of denunciation that pervaded every workplace and apartment building. Perhaps the most famous such episode began on Oct. 23, 1958, when the Nobel committee informed Soviet writer Boris Pasternak that he had been selected for the Nobel Prize in literature—and plunged the writer’s life into hell. Ever since Pasternak’s Doctor Zhivago had been first published the previous year (in Italy, since the writer could not publish it at home) the Communist Party and the Soviet literary establishment had their knives out for him. To the establishment, the Nobel Prize added insult to grave injury. A well-worn science-fiction trope imagines space travelers going into suspended animation as they head into deep space. Closer to reality are actual efforts to slow biological processes to a fraction of their normal rate by replacing blood with ice-cold saline to prevent cell death in severe trauma. But saline transfusions or other exotic measures are not ideal for ratcheting down a body’s metabolism because they risk damaging tissue.

A well-worn science-fiction trope imagines space travelers going into suspended animation as they head into deep space. Closer to reality are actual efforts to slow biological processes to a fraction of their normal rate by replacing blood with ice-cold saline to prevent cell death in severe trauma. But saline transfusions or other exotic measures are not ideal for ratcheting down a body’s metabolism because they risk damaging tissue. The John Coltrane Quartet’s “Alabama” is a strange song, incongruous with the rest of the album on which it appears. Inserted into Coltrane’s 1964 album Live at Birdland, it’s a studio track that confounds the virtuosic post-bop bliss of the album’s first three tracks, live recordings that include a jittery rendition of Mongo Santamaria’s “Afro Blue.” All of that collapses when we reach the sunken melancholy of “Alabama.” We are far, now, from the cascades of sound that Coltrane introduced us to in “Giant Steps,” far from the sonic innovations and precise phrasing he refined in this album’s live recordings. Here, Coltrane’s saxophone sounds hoarse and enfeebled, until it collapses on the threshold of a hole in the ground.

The John Coltrane Quartet’s “Alabama” is a strange song, incongruous with the rest of the album on which it appears. Inserted into Coltrane’s 1964 album Live at Birdland, it’s a studio track that confounds the virtuosic post-bop bliss of the album’s first three tracks, live recordings that include a jittery rendition of Mongo Santamaria’s “Afro Blue.” All of that collapses when we reach the sunken melancholy of “Alabama.” We are far, now, from the cascades of sound that Coltrane introduced us to in “Giant Steps,” far from the sonic innovations and precise phrasing he refined in this album’s live recordings. Here, Coltrane’s saxophone sounds hoarse and enfeebled, until it collapses on the threshold of a hole in the ground. Last summer, Nikil Saval was best known as a head editor for the literary and political magazine n+1. He wrote freelance articles about architecture and design for The New York Times and The New Yorker. He used a Motorola razr flip phone.

Last summer, Nikil Saval was best known as a head editor for the literary and political magazine n+1. He wrote freelance articles about architecture and design for The New York Times and The New Yorker. He used a Motorola razr flip phone. The World According to Physics, by the British physicist Jim Al-Khalili, looks less like a

The World According to Physics, by the British physicist Jim Al-Khalili, looks less like a