by Andrea Scrima

Ryan Ruby is a novelist, translator, critic, and poet who lives, as I do, in Berlin. Back in the summer of 2018, I attended an event at TOP, an art space in Neukölln, where along with journalist Ben Mauk and translator Anne Posten, his colleagues at the Berlin Writers’ Workshop, he was reading from work in progress. Ryan read from a project he called Context Collapse, which, if I remember correctly, he described as a “poem containing the history of poetry.” But to my ears, it sounded more like an academic paper than a poem, with jargon imported from disciplines such as media theory, economics, and literary criticism. It even contained statistics, citations from previous scholarship, and explanatory footnotes, written in blank verse, which were printed out, shuffled up, and distributed to the audience. Throughout the reading, Ryan would hold up a number on a sheet of paper corresponding to the footnote in the text, and a voice from the audience would read it aloud, creating a spatialized, polyvocal sonic environment as well as, to be perfectly honest, a feeling of information overload. Later, I asked him to send me the excerpt, so I could delve deeper into what he had written at a slower pace than readings typically afford—and I’ve been looking forward to seeing the finished project ever since. And now that it is, I am publishing the first suite of excerpts from Context Collapse at Statorec, where I am editor-in-chief.

Ryan Ruby is a novelist, translator, critic, and poet who lives, as I do, in Berlin. Back in the summer of 2018, I attended an event at TOP, an art space in Neukölln, where along with journalist Ben Mauk and translator Anne Posten, his colleagues at the Berlin Writers’ Workshop, he was reading from work in progress. Ryan read from a project he called Context Collapse, which, if I remember correctly, he described as a “poem containing the history of poetry.” But to my ears, it sounded more like an academic paper than a poem, with jargon imported from disciplines such as media theory, economics, and literary criticism. It even contained statistics, citations from previous scholarship, and explanatory footnotes, written in blank verse, which were printed out, shuffled up, and distributed to the audience. Throughout the reading, Ryan would hold up a number on a sheet of paper corresponding to the footnote in the text, and a voice from the audience would read it aloud, creating a spatialized, polyvocal sonic environment as well as, to be perfectly honest, a feeling of information overload. Later, I asked him to send me the excerpt, so I could delve deeper into what he had written at a slower pace than readings typically afford—and I’ve been looking forward to seeing the finished project ever since. And now that it is, I am publishing the first suite of excerpts from Context Collapse at Statorec, where I am editor-in-chief.

Andrea Scrima: Ryan, I wonder if it wouldn’t be a good idea to start with a little context. Tell us about the overall sweep of your poem, and how, since you mainly work in prose, you began writing it.

Ryan Ruby: Thank you for this very kind introduction, Andrea! That was a particularly memorable evening for me too, as my partner was nine months pregnant at the time, and I was worried that we’d have to rush to the hospital in the middle of the reading. But you remember quite well: a poem containing the history of poetry, with a tip of the hat to Ezra Pound, of course, who described The Cantos as “a poem containing history.” Read more »

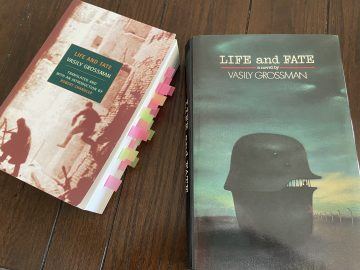

On June 22, 1941, Nazi Germany attacked the Soviet Union in a typhoon of steel and firepower without precedent in history. In spite of telltale signs and repeated warnings, Joseph Stalin who had indulged in wishful thinking was caught completely off guard. He was so stunned that he became almost catatonic, shutting himself in his dacha, not even coming out to make a formal announcement. It was days later that he regained his composure and spoke to the nation from the heart, awakening a decrepit albeit enormous war machine that would change the fate of tens of millions forever. By this time, the German juggernaut had advanced almost to the doors of Moscow, and the Soviet Union threw everything that it had to stop Hitler from breaking down the door and bringing the whole rotten structure on the Russian people’s heads, as the Führer had boasted of doing.

On June 22, 1941, Nazi Germany attacked the Soviet Union in a typhoon of steel and firepower without precedent in history. In spite of telltale signs and repeated warnings, Joseph Stalin who had indulged in wishful thinking was caught completely off guard. He was so stunned that he became almost catatonic, shutting himself in his dacha, not even coming out to make a formal announcement. It was days later that he regained his composure and spoke to the nation from the heart, awakening a decrepit albeit enormous war machine that would change the fate of tens of millions forever. By this time, the German juggernaut had advanced almost to the doors of Moscow, and the Soviet Union threw everything that it had to stop Hitler from breaking down the door and bringing the whole rotten structure on the Russian people’s heads, as the Führer had boasted of doing.

Ryan Ruby is a novelist, translator, critic, and poet who lives, as I do, in Berlin. Back in the summer of 2018, I attended an event at TOP, an art space in Neukölln, where along with journalist Ben Mauk and translator Anne Posten, his colleagues at the Berlin Writers’ Workshop, he was reading from work in progress. Ryan read from a project he called Context Collapse, which, if I remember correctly, he described as a “poem containing the history of poetry.” But to my ears, it sounded more like an academic paper than a poem, with jargon imported from disciplines such as media theory, economics, and literary criticism. It even contained statistics, citations from previous scholarship, and explanatory footnotes, written in blank verse, which were printed out, shuffled up, and distributed to the audience. Throughout the reading, Ryan would hold up a number on a sheet of paper corresponding to the footnote in the text, and a voice from the audience would read it aloud, creating a spatialized, polyvocal sonic environment as well as, to be perfectly honest, a feeling of information overload. Later, I asked him to send me the excerpt, so I could delve deeper into what he had written at a slower pace than readings typically afford—and I’ve been looking forward to seeing the finished project ever since. And now that it is, I am publishing the first suite of excerpts from Context Collapse at Statorec, where I am editor-in-chief.

Ryan Ruby is a novelist, translator, critic, and poet who lives, as I do, in Berlin. Back in the summer of 2018, I attended an event at TOP, an art space in Neukölln, where along with journalist Ben Mauk and translator Anne Posten, his colleagues at the Berlin Writers’ Workshop, he was reading from work in progress. Ryan read from a project he called Context Collapse, which, if I remember correctly, he described as a “poem containing the history of poetry.” But to my ears, it sounded more like an academic paper than a poem, with jargon imported from disciplines such as media theory, economics, and literary criticism. It even contained statistics, citations from previous scholarship, and explanatory footnotes, written in blank verse, which were printed out, shuffled up, and distributed to the audience. Throughout the reading, Ryan would hold up a number on a sheet of paper corresponding to the footnote in the text, and a voice from the audience would read it aloud, creating a spatialized, polyvocal sonic environment as well as, to be perfectly honest, a feeling of information overload. Later, I asked him to send me the excerpt, so I could delve deeper into what he had written at a slower pace than readings typically afford—and I’ve been looking forward to seeing the finished project ever since. And now that it is, I am publishing the first suite of excerpts from Context Collapse at Statorec, where I am editor-in-chief.

‘What insults my soul’,

‘What insults my soul’,  IT’S AN APPROXIMATELY

IT’S AN APPROXIMATELY One way to lose a popularity contest in the United States is to mention in polite company — who may be chatting about, say, the impeachment or the Mueller investigation — the numerous ways the United States has meddled in the affairs of other countries throughout many years.

One way to lose a popularity contest in the United States is to mention in polite company — who may be chatting about, say, the impeachment or the Mueller investigation — the numerous ways the United States has meddled in the affairs of other countries throughout many years.

Writing in The New York Times in June 2003, less than two years after the events of September 11 shattered the complacency with which many Americans conducted their lives,

Writing in The New York Times in June 2003, less than two years after the events of September 11 shattered the complacency with which many Americans conducted their lives,