Ian Parker in The New Yorker:

In 2008, Yuval Noah Harari, a young historian at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, began to write a book derived from an undergraduate world-history class that he was teaching. Twenty lectures became twenty chapters. Harari, who had previously written about aspects of medieval and early-modern warfare—but whose intellectual appetite, since childhood, had been for all-encompassing accounts of the world—wrote in plain, short sentences that displayed no anxiety about the academic decorum of a study spanning hundreds of thousands of years. It was a history of everyone, ever. The book, published in Hebrew as “A Brief History of Humankind,” became an Israeli best-seller; then, as “Sapiens,” it became an international one. Readers were offered the vertiginous pleasure of acquiring apparent mastery of all human affairs—evolution, agriculture, economics—while watching their personal narratives, even their national narratives, shrink to a point of invisibility. President Barack Obama, speaking to CNN in 2016, compared the book to a visit he’d made to the pyramids of Giza.

In 2008, Yuval Noah Harari, a young historian at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, began to write a book derived from an undergraduate world-history class that he was teaching. Twenty lectures became twenty chapters. Harari, who had previously written about aspects of medieval and early-modern warfare—but whose intellectual appetite, since childhood, had been for all-encompassing accounts of the world—wrote in plain, short sentences that displayed no anxiety about the academic decorum of a study spanning hundreds of thousands of years. It was a history of everyone, ever. The book, published in Hebrew as “A Brief History of Humankind,” became an Israeli best-seller; then, as “Sapiens,” it became an international one. Readers were offered the vertiginous pleasure of acquiring apparent mastery of all human affairs—evolution, agriculture, economics—while watching their personal narratives, even their national narratives, shrink to a point of invisibility. President Barack Obama, speaking to CNN in 2016, compared the book to a visit he’d made to the pyramids of Giza.

“Sapiens” has sold more than twelve million copies. “Three important revolutions shaped the course of history,” the book proposes. “The Cognitive Revolution kick-started history about 70,000 years ago. The Agricultural Revolution sped it up about 12,000 years ago. The Scientific Revolution, which got under way only 500 years ago, may well end history and start something completely different.” Harari’s account, though broadly chronological, is built out of assured generalization and comparison rather than dense historical detail. “Sapiens” feels like a study-guide summary of an immense, unwritten text—or, less congenially, like a ride on a tour bus that never stops for a poke around the ruins. (“As in Rome, so also in ancient China: most generals and philosophers did not think it their duty to develop new weapons.”) Harari did not invent Big History, but he updated it with hints of self-help and futurology, as well as a high-altitude, almost nihilistic composure about human suffering. He attached the time frame of aeons to the time frame of punditry—of now, and soon. His narrative of flux, of revolution after revolution, ended urgently, and perhaps conveniently, with a cliffhanger. “Sapiens,” while acknowledging that “history teaches us that what seems to be just around the corner may never materialise,” suggests that our species is on the verge of a radical redesign. Thanks to advances in computing, cyborg engineering, and biological engineering, “we may be fast approaching a new singularity, when all the concepts that give meaning to our world—me, you, men, women, love and hate—will become irrelevant.”

More here.

The world’s species and natural ecosystems are in crisis. When nearly 200 countries gather in ten days’ time to thrash out a major plan to stem the precipitous decline, China is expected to take a prominent role. The high-stakes negotiations will set the stage for a major biodiversity summit in October, which the country will also host — marking the first time the nation will lead global talks on the environment. That role as host, together with the China’s growing global influence — including its vast Belt and Road Initiative to build international infrastructure — has thrown a spotlight on its own impact on, and efforts to preserve, biodiversity. “We are familiar with China being part of the problem of the global environmental emergency. For the sake of nature and the people living on this planet, there is a need to turn China into part of the solution,” says Li Shuo, a policy adviser at Greenpeace China in Beijing.

The world’s species and natural ecosystems are in crisis. When nearly 200 countries gather in ten days’ time to thrash out a major plan to stem the precipitous decline, China is expected to take a prominent role. The high-stakes negotiations will set the stage for a major biodiversity summit in October, which the country will also host — marking the first time the nation will lead global talks on the environment. That role as host, together with the China’s growing global influence — including its vast Belt and Road Initiative to build international infrastructure — has thrown a spotlight on its own impact on, and efforts to preserve, biodiversity. “We are familiar with China being part of the problem of the global environmental emergency. For the sake of nature and the people living on this planet, there is a need to turn China into part of the solution,” says Li Shuo, a policy adviser at Greenpeace China in Beijing.

A gunshot echoed over starlit forest near the town of Marine on St. Croix, Minnesota. It was late October, already frigid, and chasers had pushed our group of ten fugitives to the edge of a lake. For a moment, we’d hesitated, shouts drawing closer as the black water winked, but the shot drove us all straight in. My legs went numb; Elyse, a high-school sophomore, exclaimed, “My God! ” Submerged to the waist, I waded through marsh grass and lamplight toward our conductor, who silently indicated the opposite bank. The Drinking Gourd shone overhead with exaggerated clarity. This was my third Underground Railroad Reënactment.

A gunshot echoed over starlit forest near the town of Marine on St. Croix, Minnesota. It was late October, already frigid, and chasers had pushed our group of ten fugitives to the edge of a lake. For a moment, we’d hesitated, shouts drawing closer as the black water winked, but the shot drove us all straight in. My legs went numb; Elyse, a high-school sophomore, exclaimed, “My God! ” Submerged to the waist, I waded through marsh grass and lamplight toward our conductor, who silently indicated the opposite bank. The Drinking Gourd shone overhead with exaggerated clarity. This was my third Underground Railroad Reënactment. On the eve of the new year, my Twitter feed and an academic listserv I frequent lit up with arguments about biology and society. Some people had a lot to say about scientific matters—birth sex, assigned sex, genes and chromosomes—while others appealed to social ones: employment rights, free speech, and gender diversity. I could tell that transgender rights lay at the heart of the matter, but why were the people who tagged me on Twitter raging at one another about biological truth? And why were the professionals on my listserv raising disturbing questions about free speech and material reality while also trying to relitigate the meanings of sex and gender?

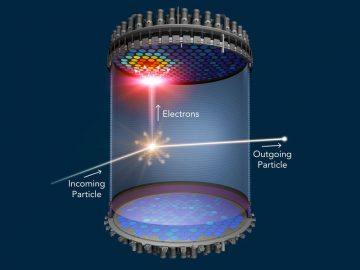

On the eve of the new year, my Twitter feed and an academic listserv I frequent lit up with arguments about biology and society. Some people had a lot to say about scientific matters—birth sex, assigned sex, genes and chromosomes—while others appealed to social ones: employment rights, free speech, and gender diversity. I could tell that transgender rights lay at the heart of the matter, but why were the people who tagged me on Twitter raging at one another about biological truth? And why were the professionals on my listserv raising disturbing questions about free speech and material reality while also trying to relitigate the meanings of sex and gender? This spring, ten tons of liquid xenon will be pumped into a tank nestled nearly a mile underground at the heart of a

This spring, ten tons of liquid xenon will be pumped into a tank nestled nearly a mile underground at the heart of a  This year more than 60 countries will hold

This year more than 60 countries will hold  What a joy it is to journey back into the Aeneid with Quint as our Sibyl. The latter warns Aeneas that in Italy he will wage wars as cruel as Troy’s, again over a stolen bride, but with aid from a Greek city. She thus articulates from within the poem its famous division into two halves, the second a repetition and reversal of the Iliad. No less inspired, but far more meticulously detailed, is Quint’s structural pronouncement: that chiasmus shapes the Aeneid’s architecture on a fractal scale, from its microscopic details to the thousand-year sweep of its plot. Expanding on this figure’s normative definition as an A-B-B-A arrangement of words, Quint elucidates a range of intertextual symmetries and reversals by which, in his argument, Vergil “double-crosses” his own epic. This grand unified theory seeks to interlink and explain the poem’s meaning, structure, and notorious “ambivalence”: the self-questioning tendencies that have prevented easy interpretation, and divided the poem’s readers, since its publication.

What a joy it is to journey back into the Aeneid with Quint as our Sibyl. The latter warns Aeneas that in Italy he will wage wars as cruel as Troy’s, again over a stolen bride, but with aid from a Greek city. She thus articulates from within the poem its famous division into two halves, the second a repetition and reversal of the Iliad. No less inspired, but far more meticulously detailed, is Quint’s structural pronouncement: that chiasmus shapes the Aeneid’s architecture on a fractal scale, from its microscopic details to the thousand-year sweep of its plot. Expanding on this figure’s normative definition as an A-B-B-A arrangement of words, Quint elucidates a range of intertextual symmetries and reversals by which, in his argument, Vergil “double-crosses” his own epic. This grand unified theory seeks to interlink and explain the poem’s meaning, structure, and notorious “ambivalence”: the self-questioning tendencies that have prevented easy interpretation, and divided the poem’s readers, since its publication. A few themes in particular resonate through this tour of quantum mechanics. The first is that people matter. That might sound obvious — you can’t have any physics if you don’t have physicists — but the point is subtler. The specific personalities matter, and they matter to specific cohorts, making them different from all other cohorts. Even when Kaiser tours the most rarefied and abstract corridors of theoretical physics, he never finds a solitary theorist mooning over a blackboard. All physics happens in conversation, whether it is Einstein and Ehrenfest joking at a physics meeting, or Schrödinger working out his famous thought experiment about a cat — killed (or not) probabilistically with a dose of poison gas — in correspondence with Einstein and other quantum dissidents. As Kaiser points out, it is no accident that, as Europe descended into fascist chaos and warmongering, “Schrödinger’s thoughts turned to poison, death, and destruction.” Even the main character of the first chapter, Paul Dirac, notorious as the weirdest weirdo to ever do theoretical physics, is presented as enmeshed in the communities that found him so inscrutable.

A few themes in particular resonate through this tour of quantum mechanics. The first is that people matter. That might sound obvious — you can’t have any physics if you don’t have physicists — but the point is subtler. The specific personalities matter, and they matter to specific cohorts, making them different from all other cohorts. Even when Kaiser tours the most rarefied and abstract corridors of theoretical physics, he never finds a solitary theorist mooning over a blackboard. All physics happens in conversation, whether it is Einstein and Ehrenfest joking at a physics meeting, or Schrödinger working out his famous thought experiment about a cat — killed (or not) probabilistically with a dose of poison gas — in correspondence with Einstein and other quantum dissidents. As Kaiser points out, it is no accident that, as Europe descended into fascist chaos and warmongering, “Schrödinger’s thoughts turned to poison, death, and destruction.” Even the main character of the first chapter, Paul Dirac, notorious as the weirdest weirdo to ever do theoretical physics, is presented as enmeshed in the communities that found him so inscrutable. Jill Herbers, a writer who lives in New Hampshire, has been canvassing for Bernie in recent weeks. “It’s a deeply human experience,” she said. “The teacher’s speaking, and so is the nurse—and so is the person in the five-million-dollar lake house, because they don’t want to see the loons damaged. People love Sanders and love what he’s for. Everyone has been brought up in this system that isn’t working anymore.” Being progressive, to her, “is just human. What’s radical is five hundred thousand people sleeping on the streets. Amazon not paying any taxes.” Sanders’s campaign was a serious one, she said, but also fun, and about love. “Cornel West says, ‘Justice is what love looks like in public.’ ” She smiled.

Jill Herbers, a writer who lives in New Hampshire, has been canvassing for Bernie in recent weeks. “It’s a deeply human experience,” she said. “The teacher’s speaking, and so is the nurse—and so is the person in the five-million-dollar lake house, because they don’t want to see the loons damaged. People love Sanders and love what he’s for. Everyone has been brought up in this system that isn’t working anymore.” Being progressive, to her, “is just human. What’s radical is five hundred thousand people sleeping on the streets. Amazon not paying any taxes.” Sanders’s campaign was a serious one, she said, but also fun, and about love. “Cornel West says, ‘Justice is what love looks like in public.’ ” She smiled. Joe Biden launched his presidential bid in April with a bold defense of the principle that “all men are created equal,” a principle he rightly argued that, from Thomas Jefferson on, “we haven’t always lived up to.” But, Mr. Biden added, this is something “we have never before walked away from,” and that’s where he went wrong. Like most Americans, the former vice president forgets the period ironically known as Redemption, the movement that followed the abolition of slavery and ended 12 years of America’s first experiment in interracial democracy — Reconstruction — with a systematic, multitiered, terrorist-backed rollback, when the defeated Confederate South, as the saying went, “rose again.”

Joe Biden launched his presidential bid in April with a bold defense of the principle that “all men are created equal,” a principle he rightly argued that, from Thomas Jefferson on, “we haven’t always lived up to.” But, Mr. Biden added, this is something “we have never before walked away from,” and that’s where he went wrong. Like most Americans, the former vice president forgets the period ironically known as Redemption, the movement that followed the abolition of slavery and ended 12 years of America’s first experiment in interracial democracy — Reconstruction — with a systematic, multitiered, terrorist-backed rollback, when the defeated Confederate South, as the saying went, “rose again.” In 2008, Yuval Noah Harari, a young historian at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, began to write a book derived from an undergraduate world-history class that he was teaching. Twenty lectures became twenty chapters. Harari, who had previously written about aspects of medieval and early-modern warfare—but whose intellectual appetite, since childhood, had been for all-encompassing accounts of the world—wrote in plain, short sentences that displayed no anxiety about the academic decorum of a study spanning hundreds of thousands of years. It was a history of everyone, ever. The book, published in Hebrew as “A Brief History of Humankind,” became an Israeli best-seller; then, as “

In 2008, Yuval Noah Harari, a young historian at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, began to write a book derived from an undergraduate world-history class that he was teaching. Twenty lectures became twenty chapters. Harari, who had previously written about aspects of medieval and early-modern warfare—but whose intellectual appetite, since childhood, had been for all-encompassing accounts of the world—wrote in plain, short sentences that displayed no anxiety about the academic decorum of a study spanning hundreds of thousands of years. It was a history of everyone, ever. The book, published in Hebrew as “A Brief History of Humankind,” became an Israeli best-seller; then, as “ I strongly suspect that at least 95% of occurrences of the phrase ‘a murder of crows’ are found in sentences like, “Did you know that a group of crows is called a ‘murder of crows’?” With this in mind, it can’t really be correct to say that a group of crows is a murder; the preponderance of occurrences of the term in sentences of the sort I just gave means that, in the other 5%, the ones where English-speakers say things like, “Look at that murder of crows,” what is in fact happening is that the speaker is drawing attention to the fact that he or she has mastered this precious bit of vocabulary. The focus of the proposition, in other words, is the speaker, and not the crows.

I strongly suspect that at least 95% of occurrences of the phrase ‘a murder of crows’ are found in sentences like, “Did you know that a group of crows is called a ‘murder of crows’?” With this in mind, it can’t really be correct to say that a group of crows is a murder; the preponderance of occurrences of the term in sentences of the sort I just gave means that, in the other 5%, the ones where English-speakers say things like, “Look at that murder of crows,” what is in fact happening is that the speaker is drawing attention to the fact that he or she has mastered this precious bit of vocabulary. The focus of the proposition, in other words, is the speaker, and not the crows. A record-breaking temperature reading taken at an Argentinian research station on the continent Thursday clocked in at 18.3 degrees Celsius — 65 degrees Fahrenheit — warmer than it is right now in Orlando, Florida, and the hottest temperature ever recorded in Antarctica.

A record-breaking temperature reading taken at an Argentinian research station on the continent Thursday clocked in at 18.3 degrees Celsius — 65 degrees Fahrenheit — warmer than it is right now in Orlando, Florida, and the hottest temperature ever recorded in Antarctica. This month, Verso is publishing Butler’s latest book, “

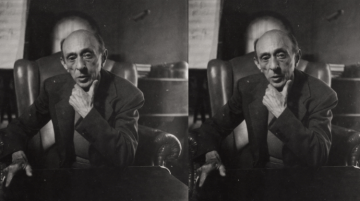

This month, Verso is publishing Butler’s latest book, “ George Steiner, who has died aged 90, was a polymathic European intellectual of particular severity. In an academic career that took him from the University of Chicago to Harvard, Oxford, Princeton, Cambridge and Geneva, Steiner held forth on tragedy, reading, the decline of literacy, the possibilities of translation, science and chess. He crossed swords with

George Steiner, who has died aged 90, was a polymathic European intellectual of particular severity. In an academic career that took him from the University of Chicago to Harvard, Oxford, Princeton, Cambridge and Geneva, Steiner held forth on tragedy, reading, the decline of literacy, the possibilities of translation, science and chess. He crossed swords with  That evening, people flooded the supermarkets, packing their carts high with instant food, rice, toilet paper and condoms. A picture of a masked woman with a cartload of Maggi Mee instant noodles was soon turned into a meme. Another image showed a condom-clad finger pressing a lift button; there had been an

That evening, people flooded the supermarkets, packing their carts high with instant food, rice, toilet paper and condoms. A picture of a masked woman with a cartload of Maggi Mee instant noodles was soon turned into a meme. Another image showed a condom-clad finger pressing a lift button; there had been an  In 1942, when Levant was back in New York City, he commissioned Schoenberg to write a piano piece for him. Expecting something short, perhaps the length of a Chopin Nocturne, Levant “wasn’t prepared,” as he later wrote, for the full-length concerto upon which the composer instead embarked. Accompanying a letter dated August 8, 1942, Schoenberg sent roughly a quarter of the manuscript to Levant. The work, Schoenberg wrote, would be in four parts and would include a scherzo, an adagio, and a rondo-like finale. But though Levant had already paid an installment of $200, a final fee for the commission had yet to be agreed upon. Schoenberg naturally wanted to finalize the details. What followed was a delicate back and forth, the two artists acting like a pair of uneasy dance partners.

In 1942, when Levant was back in New York City, he commissioned Schoenberg to write a piano piece for him. Expecting something short, perhaps the length of a Chopin Nocturne, Levant “wasn’t prepared,” as he later wrote, for the full-length concerto upon which the composer instead embarked. Accompanying a letter dated August 8, 1942, Schoenberg sent roughly a quarter of the manuscript to Levant. The work, Schoenberg wrote, would be in four parts and would include a scherzo, an adagio, and a rondo-like finale. But though Levant had already paid an installment of $200, a final fee for the commission had yet to be agreed upon. Schoenberg naturally wanted to finalize the details. What followed was a delicate back and forth, the two artists acting like a pair of uneasy dance partners.