Gwendolyn Glenn in WFAE Radio:

Henry Louis Gates, a renowned and award-winning filmmaker, author of two dozen books, a professor and director of African American studies at Harvard University, has written about race in America. He explores the Civil War, Reconstruction to Jim Crow, the civil rights movement and the state of race relations today. Gates spoke at UNC Charlotte Tuesday for the school’s 2019 Chancellor Speaker Series and at the uptown campus to school donors and city leaders. WFAE’s “All Things Considered” host, Gwendolyn Glenn, caught up with him to talk about race, voting, economics and other issues.

Henry Louis Gates, a renowned and award-winning filmmaker, author of two dozen books, a professor and director of African American studies at Harvard University, has written about race in America. He explores the Civil War, Reconstruction to Jim Crow, the civil rights movement and the state of race relations today. Gates spoke at UNC Charlotte Tuesday for the school’s 2019 Chancellor Speaker Series and at the uptown campus to school donors and city leaders. WFAE’s “All Things Considered” host, Gwendolyn Glenn, caught up with him to talk about race, voting, economics and other issues.

Gwendolyn Glenn: Let’s talk about the message that you want to leave people with. You’ll be talking with students, faculty from UNC Charlotte and also a lot of city leaders here in Charlotte. What’s the message you want to leave today?

Henry Louis Gates: It’s very important for people to understand the history of Reconstruction, the period following the Civil War and its rollback because it is a precursor to the period that we’re experiencing today. Between 1870 and 1877, 2,000 black men were elected to public office, including Chris Rock’s great-great-grandfather, who was elected to the House of Delegates in South Carolina. But within a few years, poof — all that disappeared.

Glenn: And I was going to ask you about that because you talk about that in your book and I think in an interview I heard you compare that roll back after Reconstruction to Jim Crow and on to what’s happening now with the Trump administration and that rollback.

Gates: Reconstruction was 12 years of unprecedented black freedom followed by an alt-right rollback. And we’re living through a period of eight years of a beautiful, brilliant, black family in the White House. A brilliant black president followed by an alt-right rollback. So the lesson of Reconstruction is that rights that we think are permanent, the right to vote, birthright citizenship, and the right of a woman to determine the fate of her own body. We think that these are inviolable. But they’re not they’re subject to the interpretation of the courts and sometimes the executive orders and that is the crisis that we’re facing today. So what happened in Reconstruction can happen again. The most important way, the most devastating way that Reconstruction was rolled back was through voter suppression.

More here. (Note: Throughout February, at least one post will honor The Black History Month. This year’s theme is “African Americans and the Vote.” Readers are encouraged to send in their suggestions)

Nations generally want their economies to be rich, robust, and growing. But it’s also important to person to ensure that wealth doesn’t flow only to a few people, but rather that as many people as possible can enjoy the benefits of a healthy economy. As is well known, the best way to balance these interests is a contentious subject. On one side we might find free-market fundamentalists who want to let supply and demand set prices and keep government interference to a minimum, while on the other we might find enthusiasts for very strong government control over all aspects of the economy. Suresh Naidu is an economist who has delved deeply into how economic performance affects and is affected by other notable social factors, from democracy to revolution to slavery. We talk about these, as well as how concentrations of economic power in just a few hands — monopoly and its cousin, monopsony — can distort the best intentions of the free market.

Nations generally want their economies to be rich, robust, and growing. But it’s also important to person to ensure that wealth doesn’t flow only to a few people, but rather that as many people as possible can enjoy the benefits of a healthy economy. As is well known, the best way to balance these interests is a contentious subject. On one side we might find free-market fundamentalists who want to let supply and demand set prices and keep government interference to a minimum, while on the other we might find enthusiasts for very strong government control over all aspects of the economy. Suresh Naidu is an economist who has delved deeply into how economic performance affects and is affected by other notable social factors, from democracy to revolution to slavery. We talk about these, as well as how concentrations of economic power in just a few hands — monopoly and its cousin, monopsony — can distort the best intentions of the free market. Graveyards in India are, for the most part, Muslim graveyards, because Christians make up a miniscule part of the population, and, as you know, Hindus and most other communities cremate their dead. The Muslim graveyard, the kabristan, has always loomed large in the imagination and rhetoric of Hindu nationalists. “Mussalman ka ek hi sthan, kabristan ya Pakistan!”—Only one place for the Mussalman, the graveyard or Pakistan—is among the more frequent war cries of the murderous, sword-wielding militias and vigilante mobs that have overrun India’s streets.

Graveyards in India are, for the most part, Muslim graveyards, because Christians make up a miniscule part of the population, and, as you know, Hindus and most other communities cremate their dead. The Muslim graveyard, the kabristan, has always loomed large in the imagination and rhetoric of Hindu nationalists. “Mussalman ka ek hi sthan, kabristan ya Pakistan!”—Only one place for the Mussalman, the graveyard or Pakistan—is among the more frequent war cries of the murderous, sword-wielding militias and vigilante mobs that have overrun India’s streets. A third of the way through this absorbing and engagingly written book, Albert Costa describes a family meal: “The father speaks Spanish with his wife and his son, but uses Catalan with his daughter. The daughter in turn speaks Catalan with her father but Spanish with the rest of the family, including the grandmother, who only speaks Spanish though she understands Catalan.” It’s what Costa calls “orderly mixing”, and, depending on which restaurants you visit, a common enough situation: everyone is bilingual here, but the language used changes according to who it is directed at. Given that everyone at the table understands both languages, would it not be easier and less confusing if everyone just chose one language and stuck to it? That sounds logical, but the bilingual mind doesn’t work that way. If you do not believe it, Costa suggests “having a conversation with a friend in the language you do not usually use and see how far you get”.

A third of the way through this absorbing and engagingly written book, Albert Costa describes a family meal: “The father speaks Spanish with his wife and his son, but uses Catalan with his daughter. The daughter in turn speaks Catalan with her father but Spanish with the rest of the family, including the grandmother, who only speaks Spanish though she understands Catalan.” It’s what Costa calls “orderly mixing”, and, depending on which restaurants you visit, a common enough situation: everyone is bilingual here, but the language used changes according to who it is directed at. Given that everyone at the table understands both languages, would it not be easier and less confusing if everyone just chose one language and stuck to it? That sounds logical, but the bilingual mind doesn’t work that way. If you do not believe it, Costa suggests “having a conversation with a friend in the language you do not usually use and see how far you get”. The footprints of a child are small but on November 14, 1960, six-year-old Ruby Bridges walked with purpose as she became the first African American student to integrate an elementary school in the South. This venture leads to the advancement of the Civil Rights Movement and created a pathway for further integration across the southern parts of the U.S.

The footprints of a child are small but on November 14, 1960, six-year-old Ruby Bridges walked with purpose as she became the first African American student to integrate an elementary school in the South. This venture leads to the advancement of the Civil Rights Movement and created a pathway for further integration across the southern parts of the U.S. When Darwin wrote the Origin of Species, he famously closed the book with the provocative promise that “light will be thrown on the origin of man and his history.”

When Darwin wrote the Origin of Species, he famously closed the book with the provocative promise that “light will be thrown on the origin of man and his history.” The trebling of tuition fees would unleash a new golden age for English universities, or so we were told. They would become financially sustainable, competitive, liberated from stifling bureaucracy and responsive to the needs of students. And yet, nearly a decade later, higher education is in crisis.

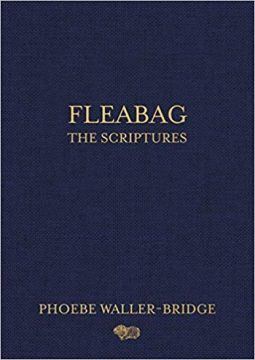

The trebling of tuition fees would unleash a new golden age for English universities, or so we were told. They would become financially sustainable, competitive, liberated from stifling bureaucracy and responsive to the needs of students. And yet, nearly a decade later, higher education is in crisis. The title of Fleabag: The Scriptures (Ballantine Books, $28) is a cheeky play on words: It refers to the shooting scripts for the television comedy Fleabag, which are reproduced here in full, and it also refers to the fact that the second (and, if creator Phoebe Waller-Bridge is to be believed, final) season of the show, which debuted on Amazon Prime in May 2019, is about the main character’s romantic attachment to an unattainable Catholic priest. But it also acknowledges that Waller-Bridge’s words—printed out on creamy paper stock, bound inside a smooth navy-blue cover, and embossed with gold serif letters like a Gideon Bible—have become a new kind of religious text, albeit one that preaches primarily to secular women living in major metropolitan areas. And there is some truth to this visual provocation: If anyone had a truly blessed year, it was Phoebe Waller-Bridge. A

The title of Fleabag: The Scriptures (Ballantine Books, $28) is a cheeky play on words: It refers to the shooting scripts for the television comedy Fleabag, which are reproduced here in full, and it also refers to the fact that the second (and, if creator Phoebe Waller-Bridge is to be believed, final) season of the show, which debuted on Amazon Prime in May 2019, is about the main character’s romantic attachment to an unattainable Catholic priest. But it also acknowledges that Waller-Bridge’s words—printed out on creamy paper stock, bound inside a smooth navy-blue cover, and embossed with gold serif letters like a Gideon Bible—have become a new kind of religious text, albeit one that preaches primarily to secular women living in major metropolitan areas. And there is some truth to this visual provocation: If anyone had a truly blessed year, it was Phoebe Waller-Bridge. A  B

B Should humanity lie back

Should humanity lie back  First, some basic facts to convey the scale of the problem. Cancer is the second most lethal disease in the U.S., behind only heart disease. More than 1.7 million Americans were diagnosed with cancer in 2018, and more than 600,000 died. Over 15 million Americans cancer survivors are alive today. Almost four out of ten people will be diagnosed in their lifetime, according to

First, some basic facts to convey the scale of the problem. Cancer is the second most lethal disease in the U.S., behind only heart disease. More than 1.7 million Americans were diagnosed with cancer in 2018, and more than 600,000 died. Over 15 million Americans cancer survivors are alive today. Almost four out of ten people will be diagnosed in their lifetime, according to  Wright

Wright

Where is philosophy in public life? Can we point to how the world in 2020 is different than it was in 2010 or 1990 because of philosophical research?

Where is philosophy in public life? Can we point to how the world in 2020 is different than it was in 2010 or 1990 because of philosophical research?