Melvin Urofsky in The New York Times:

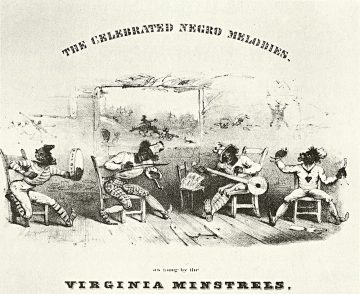

For two and a half centuries America enslaved its black population, whose labor was a critical source of the country’s capitalist modernization and prosperity. Upon the abolition of legal, interpersonal slavery, the exploitation and degradation of blacks continued in the neoslavery system of Jim Crow, a domestic terrorist regime fully sanctioned by the state and courts of the nation, and including Nazi-like instruments of ritualized human slaughter. Black harms and losses accrued to all whites, both to those directly exploiting them, and indirectly to all enjoying the enhanced prosperity their social exclusion and depressed earnings made possible. When white affirmative action was first developed on a large scale in the New Deal welfare and social programs, and later in the huge state subsidization of suburban housing — a major source of present white wealth — blacks, as the Columbia political scientist Ira Katznelson has shown, were systematically excluded, to the benefit of the millions of whites whose entitlements would have been less, or whose housing slots would have been given to blacks in any fairly administered system. In this unrelenting history of deprivation, not even the comforting cultural productions of black artists were spared: From Thomas “Daddy” Rice in the early 19th century right down to Elvis Presley, everything of value and beauty that blacks created was promptly appropriated, repackaged and sold to white audiences for the exclusive economic benefit and prestige of white performers, who often added to the injury of cultural confiscation the insult of blackface mockery.

For two and a half centuries America enslaved its black population, whose labor was a critical source of the country’s capitalist modernization and prosperity. Upon the abolition of legal, interpersonal slavery, the exploitation and degradation of blacks continued in the neoslavery system of Jim Crow, a domestic terrorist regime fully sanctioned by the state and courts of the nation, and including Nazi-like instruments of ritualized human slaughter. Black harms and losses accrued to all whites, both to those directly exploiting them, and indirectly to all enjoying the enhanced prosperity their social exclusion and depressed earnings made possible. When white affirmative action was first developed on a large scale in the New Deal welfare and social programs, and later in the huge state subsidization of suburban housing — a major source of present white wealth — blacks, as the Columbia political scientist Ira Katznelson has shown, were systematically excluded, to the benefit of the millions of whites whose entitlements would have been less, or whose housing slots would have been given to blacks in any fairly administered system. In this unrelenting history of deprivation, not even the comforting cultural productions of black artists were spared: From Thomas “Daddy” Rice in the early 19th century right down to Elvis Presley, everything of value and beauty that blacks created was promptly appropriated, repackaged and sold to white audiences for the exclusive economic benefit and prestige of white performers, who often added to the injury of cultural confiscation the insult of blackface mockery.

It is this inherited pattern of racial injustice, and its persisting inequities, that the American state and corporate system began to tackle, in a sustained manner, in the middle of the last century. The ambitious aim of Melvin I. Urofsky’s “The Affirmative Action Puzzle: A Living History From Reconstruction to Today” is a comprehensive account of the nonwhite version of affirmative action. This is a complex and challenging historical task, given that “no other issue divides Americans more.” But Urofsky, by and large, has executed it well. Following the United States Commission on Civil Rights, he defines affirmative action as a program that provides remedy for the historical and continuing discrimination suffered by certain groups; that seeks to bring about equal opportunity; and that specifies which groups are to be protected. Urofsky explores nearly all aspects of the program — its legal, educational, economic, electoral and gender dimensions, from its untitled beginnings during Reconstruction to the present.

More here. (Note: Throughout February, at least one post will honor The Black History Month. This year’s theme is “African Americans and the Vote.” Readers are encouraged to send in their suggestions)

The nuclear family is disintegrating—or so Americans might conclude from what they watch and read. The quintessential nuclear family consists of a married couple raising their children. But from Oscar-winning

The nuclear family is disintegrating—or so Americans might conclude from what they watch and read. The quintessential nuclear family consists of a married couple raising their children. But from Oscar-winning  How long have dinosaurs been around? There is one obvious sense in which they ceased to exist 66 million years ago. There is another sense in which they began to exist only around the middle of the 19th century, when Richard Owen identified a “distinct tribe… of Saurian Reptiles” in 1842. Most animals have a long history of social salience before science comes along to tell us exactly where they belong in the order of nature. Not so with dinosaurs: they didn’t have any place in society at all until science informed us of their past existence, and from that point on their salience has been entirely wrapped up in cultural representations. These representations are anchored in something real, in a way that those of unicorns are not, but the fact that we have fossilised skulls and vertebrae to point to in the case of dinosaurs, while we do not have equine skulls with a horn in the middle to point to in the case of unicorns, only makes it more difficult, not less, to understand what we may expect the folk-categorical term “dinosaur” to do.

How long have dinosaurs been around? There is one obvious sense in which they ceased to exist 66 million years ago. There is another sense in which they began to exist only around the middle of the 19th century, when Richard Owen identified a “distinct tribe… of Saurian Reptiles” in 1842. Most animals have a long history of social salience before science comes along to tell us exactly where they belong in the order of nature. Not so with dinosaurs: they didn’t have any place in society at all until science informed us of their past existence, and from that point on their salience has been entirely wrapped up in cultural representations. These representations are anchored in something real, in a way that those of unicorns are not, but the fact that we have fossilised skulls and vertebrae to point to in the case of dinosaurs, while we do not have equine skulls with a horn in the middle to point to in the case of unicorns, only makes it more difficult, not less, to understand what we may expect the folk-categorical term “dinosaur” to do. It is a journalistic convention that any author who writes a doorstopper of a book with the word “capital” in the title must be the heir to Karl Marx, while any economist whose books sell in the hundreds of thousands is a “rock star”. Thomas Piketty’s 600-page, multi-million selling

It is a journalistic convention that any author who writes a doorstopper of a book with the word “capital” in the title must be the heir to Karl Marx, while any economist whose books sell in the hundreds of thousands is a “rock star”. Thomas Piketty’s 600-page, multi-million selling  The Dolphin won the Pulitzer Prize, Lowell’s second, in 1974. It also sparked controversy, due not only to Lowell’s portrayal of Hardwick as the aggrieved, abandoned wife—the “Lizzie character,” as he called her—whom he unflatteringly contrasts throughout to the fecund Caroline character, variously imagined as dolphin, mermaid, and baby killer whale—but also due to his appropriation, and changing, of Hardwick’s letters into sonnets that voice the wife’s side of the story, whether as letter-poems or admonitory echoes that surface in the Lowell character’s head. The awkwardness here of referring to real people as characters reflects the inherent problem with Lowell’s book: the line between fact and fiction is stretched so thin—even to the point of “character” names corresponding to those of their real-life counterparts—that readers are led to assume that the book chronicles reality, not fiction, despite Lowell’s equivocal disclaimer in the final, title poem that the book is “half fiction.”

The Dolphin won the Pulitzer Prize, Lowell’s second, in 1974. It also sparked controversy, due not only to Lowell’s portrayal of Hardwick as the aggrieved, abandoned wife—the “Lizzie character,” as he called her—whom he unflatteringly contrasts throughout to the fecund Caroline character, variously imagined as dolphin, mermaid, and baby killer whale—but also due to his appropriation, and changing, of Hardwick’s letters into sonnets that voice the wife’s side of the story, whether as letter-poems or admonitory echoes that surface in the Lowell character’s head. The awkwardness here of referring to real people as characters reflects the inherent problem with Lowell’s book: the line between fact and fiction is stretched so thin—even to the point of “character” names corresponding to those of their real-life counterparts—that readers are led to assume that the book chronicles reality, not fiction, despite Lowell’s equivocal disclaimer in the final, title poem that the book is “half fiction.” Ninagawa would’ve hated being called my favorite self-Orientalist. He would’ve thrown an ashtray at me, if the stuff of legends is true. He did not brook critiques that hinted at his dabbling in the “Japanesque.” Ninagawa’s audience—his only audience, he maintained—was the Japanese, his aim “to produce a Shakespeare play that could be understood by ordinary people.” He said this with an air of finality, as if slamming a door shut, but I always wanted to jam a foot in before he did. I needed definitions—for “ordinary” and “Japanese”—his full-throated definitions, though he’d died before giving them. Because seeing his art had taught generations to stretch the bounds of those two words beyond imagining. No, here’s a more honest, selfish reason than that: I needed to know whether he was speaking to people who found them both comforting and troubling. I needed to know whether he was speaking to people like me.

Ninagawa would’ve hated being called my favorite self-Orientalist. He would’ve thrown an ashtray at me, if the stuff of legends is true. He did not brook critiques that hinted at his dabbling in the “Japanesque.” Ninagawa’s audience—his only audience, he maintained—was the Japanese, his aim “to produce a Shakespeare play that could be understood by ordinary people.” He said this with an air of finality, as if slamming a door shut, but I always wanted to jam a foot in before he did. I needed definitions—for “ordinary” and “Japanese”—his full-throated definitions, though he’d died before giving them. Because seeing his art had taught generations to stretch the bounds of those two words beyond imagining. No, here’s a more honest, selfish reason than that: I needed to know whether he was speaking to people who found them both comforting and troubling. I needed to know whether he was speaking to people like me. In October 1726 some ‘strange, but well attested’ news emerged from Godalming near Guildford. An ‘eminent’ surgeon, a male midwife, had delivered a poor woman called Mary Toft not of a child but of rabbits – a number of them, over a period of several weeks. None of the rabbits, not even a ‘perfect’ one, survived their birth, but the surgeon bottled them up and declared his intention to present them as specimens to the Royal Society. A report in the British Gazeteer furnished readers with the woman’s explanation. Some months earlier she and other women working in a field had chased a rabbit and failed to catch it. She was pregnant at the time and suffered a miscarriage. Thereafter, she pined to eat rabbit and had been unable to avoid thinking of rabbits.

In October 1726 some ‘strange, but well attested’ news emerged from Godalming near Guildford. An ‘eminent’ surgeon, a male midwife, had delivered a poor woman called Mary Toft not of a child but of rabbits – a number of them, over a period of several weeks. None of the rabbits, not even a ‘perfect’ one, survived their birth, but the surgeon bottled them up and declared his intention to present them as specimens to the Royal Society. A report in the British Gazeteer furnished readers with the woman’s explanation. Some months earlier she and other women working in a field had chased a rabbit and failed to catch it. She was pregnant at the time and suffered a miscarriage. Thereafter, she pined to eat rabbit and had been unable to avoid thinking of rabbits. Minstrel shows, most often with white entertainers performing in blackface, were a highly racist phenomenon that were a pervasive form of entertainment in America for over 80 years through the 1800s and early 1900s. Yet as complicated and fundamentally offensive as they were, it was part of what led to a break with a purely European music tradition: “African Americans were leading the way in breaking with European musical tradition, and, strange as it might seem, this break had been anticipated, and maybe even urged, by the minstrel show, the first form of musical theater to reach the whole country. Its history is much longer than the eighty or so years that it is said to have lasted in the United States; its legacy is far more complicated than just a matter of white people copying black people, and even today questions about the sources of this music and its influence remain unsettled.

Minstrel shows, most often with white entertainers performing in blackface, were a highly racist phenomenon that were a pervasive form of entertainment in America for over 80 years through the 1800s and early 1900s. Yet as complicated and fundamentally offensive as they were, it was part of what led to a break with a purely European music tradition: “African Americans were leading the way in breaking with European musical tradition, and, strange as it might seem, this break had been anticipated, and maybe even urged, by the minstrel show, the first form of musical theater to reach the whole country. Its history is much longer than the eighty or so years that it is said to have lasted in the United States; its legacy is far more complicated than just a matter of white people copying black people, and even today questions about the sources of this music and its influence remain unsettled. Soon after the violence began, on 5 January, Aamir was standing outside a residence hall in Jawaharlal Nehru University in south Delhi. Aamir, a PhD student, is Muslim, and he asked to be identified only by his first name. He had come to return a book to a classmate when he saw 50 or 60 people approaching the building. They carried metal rods, cricket bats and rocks. One swung a sledgehammer. They were yelling slogans: “Shoot the traitors to the nation!” was a common one. Later, Aamir learned that they had spent the previous half-hour assaulting a gathering of teachers and students down the road. Their faces were masked, but some were still recognisable as members of a Hindu nationalist student group that has become increasingly powerful over the past few years.

Soon after the violence began, on 5 January, Aamir was standing outside a residence hall in Jawaharlal Nehru University in south Delhi. Aamir, a PhD student, is Muslim, and he asked to be identified only by his first name. He had come to return a book to a classmate when he saw 50 or 60 people approaching the building. They carried metal rods, cricket bats and rocks. One swung a sledgehammer. They were yelling slogans: “Shoot the traitors to the nation!” was a common one. Later, Aamir learned that they had spent the previous half-hour assaulting a gathering of teachers and students down the road. Their faces were masked, but some were still recognisable as members of a Hindu nationalist student group that has become increasingly powerful over the past few years. Numbers have a certain mystique: They seem precise, exact, sometimes even beyond doubt. But outside the field of pure mathematics, this reputation rarely is deserved. And when it comes to the coronavirus epidemic, buying into that can be downright dangerous.

Numbers have a certain mystique: They seem precise, exact, sometimes even beyond doubt. But outside the field of pure mathematics, this reputation rarely is deserved. And when it comes to the coronavirus epidemic, buying into that can be downright dangerous. More than a decade after the financial crises of 2008, the shortcomings of the government’s response have become painfully clear.

More than a decade after the financial crises of 2008, the shortcomings of the government’s response have become painfully clear. We bad-movie watchers have our own anticriteria, the sorts of badness we prefer. Some of us use the term “bad movies” to mean, simply, films that emerge from a supposedly lowbrow genre, or films that are stylized in the manner we tend to label “camp.” (

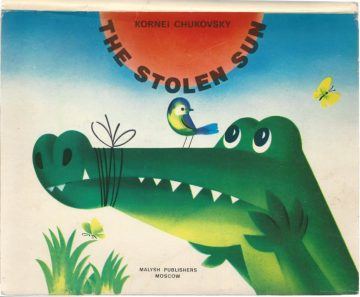

We bad-movie watchers have our own anticriteria, the sorts of badness we prefer. Some of us use the term “bad movies” to mean, simply, films that emerge from a supposedly lowbrow genre, or films that are stylized in the manner we tend to label “camp.” ( Russia had a Dr. Seuss. Same deal as ours, except his hot decade wasn’t the fifties; it was the twenties. There’s a lot to be said here.

Russia had a Dr. Seuss. Same deal as ours, except his hot decade wasn’t the fifties; it was the twenties. There’s a lot to be said here.

What does a healthy forest look like? A seemingly thriving, verdant wilderness can conceal signs of pollution, disease or invasive species. Only an ecologist can spot problems that could jeopardize the long-term well-being of the entire ecosystem. Microbiome researchers grapple with the same problem. Disruptions to the community of microbes living in the human gut can contribute to the risk and severity of a host of medical conditions. Accordingly, many scientists have become accomplished bacterial naturalists, labouring to catalogue the startling diversity of these commensal communities. Some 500–1,000 bacterial species reside in each person’s intestinal tract, alongside an undetermined number of viruses, fungi and other microbes. Rapid advances in DNA sequencing technology have accelerated the identification of these bacteria, allowing researchers to create ‘field guides’ to the species in the human gut. “We’re starting to get a feeling of who the players are,” says Jeroen Raes, a bioinformatician at VIB, a life-sciences institute in Ghent, Belgium. “But there is still considerable ‘dark matter’.”

What does a healthy forest look like? A seemingly thriving, verdant wilderness can conceal signs of pollution, disease or invasive species. Only an ecologist can spot problems that could jeopardize the long-term well-being of the entire ecosystem. Microbiome researchers grapple with the same problem. Disruptions to the community of microbes living in the human gut can contribute to the risk and severity of a host of medical conditions. Accordingly, many scientists have become accomplished bacterial naturalists, labouring to catalogue the startling diversity of these commensal communities. Some 500–1,000 bacterial species reside in each person’s intestinal tract, alongside an undetermined number of viruses, fungi and other microbes. Rapid advances in DNA sequencing technology have accelerated the identification of these bacteria, allowing researchers to create ‘field guides’ to the species in the human gut. “We’re starting to get a feeling of who the players are,” says Jeroen Raes, a bioinformatician at VIB, a life-sciences institute in Ghent, Belgium. “But there is still considerable ‘dark matter’.”