Deborah Copaken in The Atlantic:

By the time of her arrival at Harvard the following fall––now Liz instead of Lizzie––she was instantly college famous. Within weeks on campus, everyone knew who Liz Wurtzel was. How could you not? Particularly after the popped-cherry party she threw midyear. Or rather, our mutual friend Donal Logue threw the party, and Liz commandeered it. “So the story is we threw a huge party sophomore year in Adams House,” said Donal earlier today, when we spoke to commiserate over her death. “Liz, a freshman at the time, showed up and announced she had just lost her virginity and it was now officially the ‘Elizabeth Wurtzel lost her virginity party.’ At first, I was surprised. She seemed so wild. When I got to know her and understood her Ramaz background, her high-school life, it made sense.”

By the time of her arrival at Harvard the following fall––now Liz instead of Lizzie––she was instantly college famous. Within weeks on campus, everyone knew who Liz Wurtzel was. How could you not? Particularly after the popped-cherry party she threw midyear. Or rather, our mutual friend Donal Logue threw the party, and Liz commandeered it. “So the story is we threw a huge party sophomore year in Adams House,” said Donal earlier today, when we spoke to commiserate over her death. “Liz, a freshman at the time, showed up and announced she had just lost her virginity and it was now officially the ‘Elizabeth Wurtzel lost her virginity party.’ At first, I was surprised. She seemed so wild. When I got to know her and understood her Ramaz background, her high-school life, it made sense.”

Now Donal and everyone else who knew Liz, or has encountered her work since, are trying to make sense of the idea that she’s gone. Elizabeth Wurtzel died on January 7, 2020, at the age of 52, of complications from breast cancer. When I spoke with Roberta Feldman Brzezinski, her college roommate and friend ever since, she remembered Liz as “brilliant, acerbic, volatile, and fiercely loyal. In her last years, she became a fountain of life wisdom. Why do you care how people behave? You are the star of your own drama, and everyone else is just a bit player. In her case, that was epically true.”

…Wurtzel’s 1994 memoir, Prozac Nation, forever changed the literary landscape. It redefined not only what women were allowed to write about, but when they were allowed to write about it: their messy, early decades in medias res. Mental illness was no longer something to be hidden or shameful. It was a topic like any other, to be brought out into the light. Liz was suddenly the It Girl in New York, throwing epic, unforgettable parties in her loft. Suddenly, in the same way that she’d once drawn courage from my teenage writing, I now drew courage from her literary descriptions of early adulthood. “You should write about your war-photography years,” she urged me during one of her parties. And so I did. From then on, whenever anyone wanted to criticize women memoirists for oversharing; or dismiss personal writing as lesser or not literary; or shame us for describing, in intimate detail, the joys and miseries of human love, in all of its messy glory, we’d get lumped in together or collectively shamed as examples of what not to do. As the years wore on, we sometimes even found ourselves “oversharing” on the same stage.

More here. (Note: For my niece, Alia Raza, who sat many hours by Liz’s side as she lay dying, and mourned and grieved her friend in a thousand silent ways. RIP Liz)

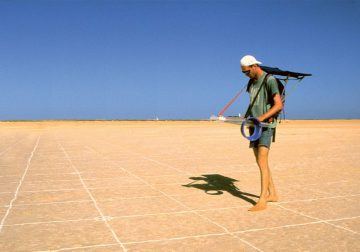

The fear of getting lost and being unable to find our way home is woven into the stories we hear as children: it can haunt us for years. Humanity’s navigational skills are poor and increasingly rarely used, leaving us to view feats of animal navigation with a mixture of envy and admiration. How do Atlantic salmon find their way back to the streams where they were born, after up to three years at sea? How do Arctic terns find their breeding sites in the far north after excursions of more than 70,000 kilometres to the Antarctic? Desert Navigator is the story of how a tiny ant (Cataglyphis spp.) became the ideal model organism for the study of animal navigation. It begins 50 years ago in a vast Saharan salt pan, where a lone, shiny black ant caught the eye of neuroethologist Rüdiger Wehner as it scuttled across the sand. Eventually, it discovered the corpse of a large fly, gripped it firmly in its mandibles, and then performed the manoeuvre that launched Wehner’s field of research.

The fear of getting lost and being unable to find our way home is woven into the stories we hear as children: it can haunt us for years. Humanity’s navigational skills are poor and increasingly rarely used, leaving us to view feats of animal navigation with a mixture of envy and admiration. How do Atlantic salmon find their way back to the streams where they were born, after up to three years at sea? How do Arctic terns find their breeding sites in the far north after excursions of more than 70,000 kilometres to the Antarctic? Desert Navigator is the story of how a tiny ant (Cataglyphis spp.) became the ideal model organism for the study of animal navigation. It begins 50 years ago in a vast Saharan salt pan, where a lone, shiny black ant caught the eye of neuroethologist Rüdiger Wehner as it scuttled across the sand. Eventually, it discovered the corpse of a large fly, gripped it firmly in its mandibles, and then performed the manoeuvre that launched Wehner’s field of research.

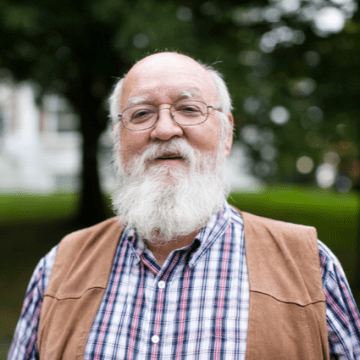

Wilfrid Sellars described the task of philosophy as explaining how things, in the broadest sense of term, hang together, in the broadest sense of the term. (Substitute “exploring” for “explaining” and you’d have a good mission statement for the Mindscape podcast.) Few modern thinkers have pursued this goal more energetically, creatively, and entertainingly than Daniel Dennett. One of the most respected philosophers of our time, Dennett’s work has ranged over topics such as consciousness, artificial intelligence, metaphysics, free will, evolutionary biology, epistemology, and naturalism, always with an eye on our best scientific understanding of the phenomenon in question. His thinking in these areas is exceptionally lucid, and he has the rare ability to express his ideas in ways that non-specialists can find accessible and compelling. We talked about all of them, in a wide-ranging and wonderfully enjoyable conversation.

Wilfrid Sellars described the task of philosophy as explaining how things, in the broadest sense of term, hang together, in the broadest sense of the term. (Substitute “exploring” for “explaining” and you’d have a good mission statement for the Mindscape podcast.) Few modern thinkers have pursued this goal more energetically, creatively, and entertainingly than Daniel Dennett. One of the most respected philosophers of our time, Dennett’s work has ranged over topics such as consciousness, artificial intelligence, metaphysics, free will, evolutionary biology, epistemology, and naturalism, always with an eye on our best scientific understanding of the phenomenon in question. His thinking in these areas is exceptionally lucid, and he has the rare ability to express his ideas in ways that non-specialists can find accessible and compelling. We talked about all of them, in a wide-ranging and wonderfully enjoyable conversation. On January 3, the United States assassinated Qassem Suleimani, a top Iranian military commander, while he was leaving Baghdad International Airport in a car with Abu Mahdi al-Muhandis, an Iraqi leader of Kata’ib Hezbollah, an Iran-backed militia. All the occupants of the car were killed.

On January 3, the United States assassinated Qassem Suleimani, a top Iranian military commander, while he was leaving Baghdad International Airport in a car with Abu Mahdi al-Muhandis, an Iraqi leader of Kata’ib Hezbollah, an Iran-backed militia. All the occupants of the car were killed. JP: Can you talk about how that subculture existed? Was it connected by magazines, or was there an online culture—or was it books that you read in translation or books by other Chinese writers? What was the material connection that made you a fandom?

JP: Can you talk about how that subculture existed? Was it connected by magazines, or was there an online culture—or was it books that you read in translation or books by other Chinese writers? What was the material connection that made you a fandom? THE PLOT OF

THE PLOT OF In 1956, in a central London café, Lindsay Anderson, Karel Reisz, Tony Richardson, and Lorenza Mazzetti wrote a manifesto for what they termed the “Free Cinema” movement. Among the aims of these four young, avant-garde filmmakers was a belief in “the importance of people and the significance of the everyday.” They eschewed traditional box office appeal in favor of authentic depictions of the quotidian, particularly that of the ordinary working man and woman. Mazzetti, who died this past weekend at the age of ninety-two, was then only twenty-eight years old—she’d recently moved to England from her native Italy, and first gotten work as a potato picker. Later that year, her second film, Together—which follows two deaf-mutes through the bomb-wrecked streets of London’s East End, or as Mazzetti described it, “fields of ruins overrun by children”—would win the Prix de Recherche at Cannes Film Festival. Her first film, K (1954), “suggested by” Kafka’s Metamorphosis and made on the most shoestring of budgets while she was a student at the Slade School of Art, anticipated the Free Cinema movement, and her signature appears first on the manifesto. And yet today she’s the least commemorated of the four, and her name is often little more than a footnote to the group’s history.

In 1956, in a central London café, Lindsay Anderson, Karel Reisz, Tony Richardson, and Lorenza Mazzetti wrote a manifesto for what they termed the “Free Cinema” movement. Among the aims of these four young, avant-garde filmmakers was a belief in “the importance of people and the significance of the everyday.” They eschewed traditional box office appeal in favor of authentic depictions of the quotidian, particularly that of the ordinary working man and woman. Mazzetti, who died this past weekend at the age of ninety-two, was then only twenty-eight years old—she’d recently moved to England from her native Italy, and first gotten work as a potato picker. Later that year, her second film, Together—which follows two deaf-mutes through the bomb-wrecked streets of London’s East End, or as Mazzetti described it, “fields of ruins overrun by children”—would win the Prix de Recherche at Cannes Film Festival. Her first film, K (1954), “suggested by” Kafka’s Metamorphosis and made on the most shoestring of budgets while she was a student at the Slade School of Art, anticipated the Free Cinema movement, and her signature appears first on the manifesto. And yet today she’s the least commemorated of the four, and her name is often little more than a footnote to the group’s history. The history of medicine abounds with oddball characters and bizarre events. Yet few figures are quite as eccentric as the French neurologist

The history of medicine abounds with oddball characters and bizarre events. Yet few figures are quite as eccentric as the French neurologist Mr. Serhal grew up in Lebanon but studied wildlife management at Oklahoma State University, graduating in 1982, at the height of the Lebanese civil war. His plan was to return and establish a hunting farm in Lebanon. But he abandoned it when, while using binoculars for the first time, he watched as a bobwhite quail hen — a game bird — ushered her chicks from bush to bush. “That gave me the shock of my life,” he said. His binoculars revealed a different way of viewing nature: “When you go to the field as a hunter with a gun, you don’t see the bird. The minute you flush it, you shoot.”

Mr. Serhal grew up in Lebanon but studied wildlife management at Oklahoma State University, graduating in 1982, at the height of the Lebanese civil war. His plan was to return and establish a hunting farm in Lebanon. But he abandoned it when, while using binoculars for the first time, he watched as a bobwhite quail hen — a game bird — ushered her chicks from bush to bush. “That gave me the shock of my life,” he said. His binoculars revealed a different way of viewing nature: “When you go to the field as a hunter with a gun, you don’t see the bird. The minute you flush it, you shoot.” Schoolteachers across the grades are responsible for teaching their students how to write. Their essential pedagogical role is instrumental. With particular attention paid to format, grammar, spelling, and syntax, students ideally learn to write what they know, think, or have learned. It matters little if the student is in a class for “creative writing” or “composition,” writing is taught and practiced as a way to record thoughts, compose ideas in a coherent manner, and clearly communicate information. A student’s writing is then assessed for how well she adhered to these instrumental standards while the teacher is assessed for how well she adhered to the standards of instrumental teaching.

Schoolteachers across the grades are responsible for teaching their students how to write. Their essential pedagogical role is instrumental. With particular attention paid to format, grammar, spelling, and syntax, students ideally learn to write what they know, think, or have learned. It matters little if the student is in a class for “creative writing” or “composition,” writing is taught and practiced as a way to record thoughts, compose ideas in a coherent manner, and clearly communicate information. A student’s writing is then assessed for how well she adhered to these instrumental standards while the teacher is assessed for how well she adhered to the standards of instrumental teaching.

1.

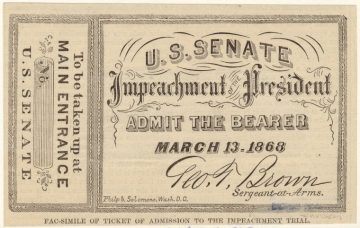

1. I have an awful confession to make. I haven’t made up my mind about whether President Trump should be convicted and removed from office.

I have an awful confession to make. I haven’t made up my mind about whether President Trump should be convicted and removed from office. When Bob Dylan was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 2016, the poet Nora Gomringer expressed her satisfaction at the recognition thus afforded not only poetry, but in particular songwriting, which she identified as the very wellspring and guarantee of literature, citing in her appraisal such classical forebears as Sappho and Homer. In an article published in the Neue Zürcher Zeitung, Gomringer mocked the conventional Western view of letters, a canon founded on prose and the novel, and now challenged by the award to Bob Dylan: “Literature is serious, it is beautiful, it is a vehicle for the noble and the grand; poetry is for what is light, for the aesthetically beautiful, it can be hermetic or tender, it can tell its story in a ballad and, if especially well made, can invite composers to set it to music…”. But “such categories”, she went on to suggest, “are stumbling blocks and increasingly unsatisfying, since they have ceased to function”, in part because of the Academy’s willingness to step outside its comfort zone and award the prize to a popular “singer/songwriter”.

When Bob Dylan was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 2016, the poet Nora Gomringer expressed her satisfaction at the recognition thus afforded not only poetry, but in particular songwriting, which she identified as the very wellspring and guarantee of literature, citing in her appraisal such classical forebears as Sappho and Homer. In an article published in the Neue Zürcher Zeitung, Gomringer mocked the conventional Western view of letters, a canon founded on prose and the novel, and now challenged by the award to Bob Dylan: “Literature is serious, it is beautiful, it is a vehicle for the noble and the grand; poetry is for what is light, for the aesthetically beautiful, it can be hermetic or tender, it can tell its story in a ballad and, if especially well made, can invite composers to set it to music…”. But “such categories”, she went on to suggest, “are stumbling blocks and increasingly unsatisfying, since they have ceased to function”, in part because of the Academy’s willingness to step outside its comfort zone and award the prize to a popular “singer/songwriter”.