by Joseph Shieber

It is a great shame that the authors of the recently released AAUP statement “In Defense of Knowledge and Higher Education” do not even know what it is that they are attempting to defend. And it is the height of irony that, in an essay attempting to defend the importance of expert knowledge, the authors of the AAUP would be so cavalier in their rejection of expert knowledge about the very subject of their defense, namely knowledge itself.

The authors of the AAUP report have a laudable goal in mind. They seek to defend the importance of, as they put it, “the disciplines and institutions that produce and transmit … knowledge”.

The authors correctly note that recent critics of higher education mistakenly confuse the teaching and research conducted at colleges and universities with indoctrination. They quote the current United States Secretary of the Department of Education, Betsy DeVos, who exhorted college students to “fight against the education establishment”. “The faculty, from adjunct professors to deans,” DeVos warned the students, “tell you what to do, what to say, and more ominously, what to think.”

Although they aren’t terribly clear, it would seem that the AAUP report authors push back against DeVos’s conflation of education with indoctrination on the basis of three important qualities of research and education at higher education institutions:

1. College and university professors develop and transmit valuable thinking methods and skills — examples that the authors cite include learning how to “solve differential equations”, “to predict the path of a hurricane”, “to track the epidemic of opioid addiction”, “to study the impact of tariffs on the economy”.

2. College and university professors discover and disseminate factual information — examples that the authors cite include “the principles of quantum mechanics”, “the somatic effects of nicotine”, and “the history of slavery and Jim Crow, or the history of the Holocaust”.

3. In addition to those discipline-specific thinking methods and bodies of factual information, college and university professors also inculcate in students an appreciation for the methods of investigation appropriate to knowledge-seeking, which the authors characterize as “informed, dispassionate investigation”.

So far, so good! If the authors of the AAUP report had stopped here, they would have done higher education — and, indeed, the general public who derive so much from the fruits of higher education — a great service.

Unfortunately, they didn’t stop here. Read more »

Berry is a serious Christian, and also a serious reader of poetry. His prose is studded with quotations from the Bible and the poetic canon. It may be surprising (though it shouldn’t be, really) how easy it is to find a text in Homer, Virgil, Dante, Shakespeare, Blake, or Wordsworth celebrating humility, fortitude, magnanimity, chastity, marital fidelity, or some other Christian (though not exclusively Christian) virtue. Character and virtue are indeed fragile, and it’s reasonable to exploit all the resources of human culture to shore them up. But although it lends his writing gravity and grace, I’m sorry that Berry insists on giving the agrarian ethos a religious framework and on situating human flourishing within a “Great Economy,” by which he means not Gaia but the “Kingdom of God.” As a result, he speaks less persuasively than he might to those of us who feel that our civilization has somehow gone wrong, and that at least some part of traditional wisdom is indeed wisdom, but who cannot believe that this universe is the work of the Christian God, or of any God. And yet we need Berry’s preaching as much as anyone. Jesus came, after all, to call sinners, not the just, to good farming practices.

Berry is a serious Christian, and also a serious reader of poetry. His prose is studded with quotations from the Bible and the poetic canon. It may be surprising (though it shouldn’t be, really) how easy it is to find a text in Homer, Virgil, Dante, Shakespeare, Blake, or Wordsworth celebrating humility, fortitude, magnanimity, chastity, marital fidelity, or some other Christian (though not exclusively Christian) virtue. Character and virtue are indeed fragile, and it’s reasonable to exploit all the resources of human culture to shore them up. But although it lends his writing gravity and grace, I’m sorry that Berry insists on giving the agrarian ethos a religious framework and on situating human flourishing within a “Great Economy,” by which he means not Gaia but the “Kingdom of God.” As a result, he speaks less persuasively than he might to those of us who feel that our civilization has somehow gone wrong, and that at least some part of traditional wisdom is indeed wisdom, but who cannot believe that this universe is the work of the Christian God, or of any God. And yet we need Berry’s preaching as much as anyone. Jesus came, after all, to call sinners, not the just, to good farming practices. Housekeeping, now nearing its fortieth anniversary, has returned to me throughout my writing career. Like those enraptured critics, in my first encounters I read for language, for voice, for craft. I loved this book. In graduate school, in a seminar on the literature of travel and trains, my professor recited the opening line to the class with a kind of disgusted glee: “My name is Ruth.” What kind of beginning was this? How had such an otherwise beautifully written book gotten away with it? The declaration—harsh, direct—is perhaps more shocking in the context of the rest of the novel, which proceeds with the gentle indifference of understatement. That opening chapter describes a mass drowning as no more upsetting than an exploratory dive: a train “nosed” into a lake, Ruth tells us, as calmly as a “weasel,” claiming all the passengers within as the water “sealed itself” over their souls. The scene is so soft, so seductive, it may as well have been narrated by a ghost. I remember we spent the remaining hour of that class discussing whether drowning truly was the most romantic way to die. I wonder now if perhaps parting from one’s body becomes more appallingly beautiful when alibied by the suggestion of an afterlife.

Housekeeping, now nearing its fortieth anniversary, has returned to me throughout my writing career. Like those enraptured critics, in my first encounters I read for language, for voice, for craft. I loved this book. In graduate school, in a seminar on the literature of travel and trains, my professor recited the opening line to the class with a kind of disgusted glee: “My name is Ruth.” What kind of beginning was this? How had such an otherwise beautifully written book gotten away with it? The declaration—harsh, direct—is perhaps more shocking in the context of the rest of the novel, which proceeds with the gentle indifference of understatement. That opening chapter describes a mass drowning as no more upsetting than an exploratory dive: a train “nosed” into a lake, Ruth tells us, as calmly as a “weasel,” claiming all the passengers within as the water “sealed itself” over their souls. The scene is so soft, so seductive, it may as well have been narrated by a ghost. I remember we spent the remaining hour of that class discussing whether drowning truly was the most romantic way to die. I wonder now if perhaps parting from one’s body becomes more appallingly beautiful when alibied by the suggestion of an afterlife. In its most common form, which scientists call the white mutant, the axolotl resembles what the translucid foetus of a cross between an otter and a shortfin eel might look like. On the internet, it is celebrated for its anthropoid smile; in Mexico, where the Aztecs once hailed as it as a godly incarnation, it is an insult to say that someone looks like one. Behind its blunt and flattened head extends a distended torso resolving into a long, ichthyic tail. The axolotl can grow to nearly a foot in length; four tiny legs dangle off its body like evolutionary afterthoughts. It wears a collar of what seem to be red feathers behind each cheek, and these ciliated gill stalks float and tremble and gently splay in the water, like the plumage in a burlesque fan. They grow back if you cut them off, too. Precisely how the animal accomplishes this, or any of its feats of regrowth, is not well understood.

In its most common form, which scientists call the white mutant, the axolotl resembles what the translucid foetus of a cross between an otter and a shortfin eel might look like. On the internet, it is celebrated for its anthropoid smile; in Mexico, where the Aztecs once hailed as it as a godly incarnation, it is an insult to say that someone looks like one. Behind its blunt and flattened head extends a distended torso resolving into a long, ichthyic tail. The axolotl can grow to nearly a foot in length; four tiny legs dangle off its body like evolutionary afterthoughts. It wears a collar of what seem to be red feathers behind each cheek, and these ciliated gill stalks float and tremble and gently splay in the water, like the plumage in a burlesque fan. They grow back if you cut them off, too. Precisely how the animal accomplishes this, or any of its feats of regrowth, is not well understood.

Lili Marleen is one of the best known songs of the twentieth century. A plaintive expression of a soldier’s desire to be with his girlfriend, it is indelibly associated with World War II, in part because it was popular with soldiers on both sides. It was

Lili Marleen is one of the best known songs of the twentieth century. A plaintive expression of a soldier’s desire to be with his girlfriend, it is indelibly associated with World War II, in part because it was popular with soldiers on both sides. It was  Marlene Dietrich, who worked tirelessly during world war two entertaining allied troops, also recorded both a

Marlene Dietrich, who worked tirelessly during world war two entertaining allied troops, also recorded both a

While waiting, shivering and jetlagged, for a train home from the Paris airport this week, I alternately stared into space and checked the train timetables. My train was an hour late. I later learned, thanks to the friendliness of a fellow traingoer, that the train had hit a deer.

While waiting, shivering and jetlagged, for a train home from the Paris airport this week, I alternately stared into space and checked the train timetables. My train was an hour late. I later learned, thanks to the friendliness of a fellow traingoer, that the train had hit a deer.

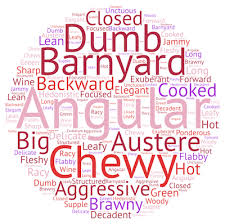

Wine writers, especially those who write wine reviews, are often derided for the flowery, overly imaginative language they use to describe wines. Some of the complainants are consumers baffled by what descriptors such as “brooding” or “flamboyant” might mean. Other complainants are experts who wish wine language had the precision of scientific discourse. The Journal of Wine Economists

Wine writers, especially those who write wine reviews, are often derided for the flowery, overly imaginative language they use to describe wines. Some of the complainants are consumers baffled by what descriptors such as “brooding” or “flamboyant” might mean. Other complainants are experts who wish wine language had the precision of scientific discourse. The Journal of Wine Economists

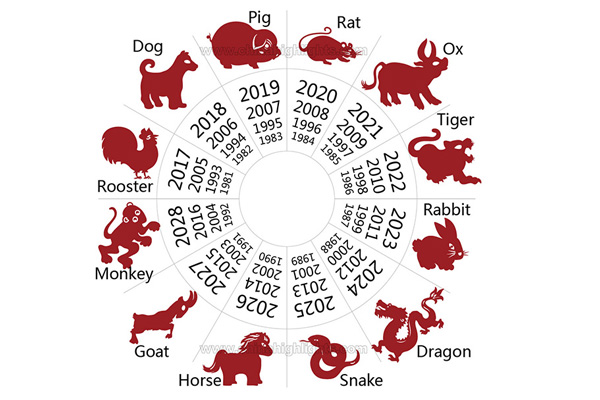

In the Chinese calendar, 2015 was the year of the sheep. I’m a sheep, and I briefly got into it. When you’re a sheep, you gotta own it.

In the Chinese calendar, 2015 was the year of the sheep. I’m a sheep, and I briefly got into it. When you’re a sheep, you gotta own it. In 1956, Vladimir Nabokov was defending his novel Lolita against claims of anti-Americanism. He called them preposterous. The accusation of anti-American bias in Lolita was based on the novel’s treatment of postwar America’s mass culture, which the novel’s European narrator does register with a mixture of skepticism and exhilaration. But this contempt, Nabokov wrote in an afterword to the book, was Humbert’s, not his own. His intention, he argued, was to analyse America from the perspective of a newly-minted American author. To steep himself in the baffling world of roadside service that seemed to characterize his new home.

In 1956, Vladimir Nabokov was defending his novel Lolita against claims of anti-Americanism. He called them preposterous. The accusation of anti-American bias in Lolita was based on the novel’s treatment of postwar America’s mass culture, which the novel’s European narrator does register with a mixture of skepticism and exhilaration. But this contempt, Nabokov wrote in an afterword to the book, was Humbert’s, not his own. His intention, he argued, was to analyse America from the perspective of a newly-minted American author. To steep himself in the baffling world of roadside service that seemed to characterize his new home. In the beginning was beer. Well, not quite at the beginning: there was no beer at the Big Bang. Curiously, though, as Rob DeSalle and Ian Tattersall point out in A Natural History of Beer, the main components of beer—ethanol and water—are found in the vast clouds swirling around the center of the Milky Way in sufficient quantity to produce 100 octillion liters of the stuff, though only at a very disappointing 0.001 proof. On earth, beer-like substances have long existed whenever grains, nectar, or fruits have spontaneously fermented. Chimps and other mammals in the wild have been observed getting sloshed on naturally occurring alcohol, which strongly suggests that very early humans did so too. Whatever the precise date of the first tipple, beer is a truly venerable article, coeval with human civilization and, of course, with some pretty uncivilized behavior as well. DeSalle and Tattersall tell its story with enormous erudition and panache.

In the beginning was beer. Well, not quite at the beginning: there was no beer at the Big Bang. Curiously, though, as Rob DeSalle and Ian Tattersall point out in A Natural History of Beer, the main components of beer—ethanol and water—are found in the vast clouds swirling around the center of the Milky Way in sufficient quantity to produce 100 octillion liters of the stuff, though only at a very disappointing 0.001 proof. On earth, beer-like substances have long existed whenever grains, nectar, or fruits have spontaneously fermented. Chimps and other mammals in the wild have been observed getting sloshed on naturally occurring alcohol, which strongly suggests that very early humans did so too. Whatever the precise date of the first tipple, beer is a truly venerable article, coeval with human civilization and, of course, with some pretty uncivilized behavior as well. DeSalle and Tattersall tell its story with enormous erudition and panache. Judith Butler is arguably the most influential critical theorist of our era. Her early books, such as Gender Trouble (1990) and Bodies That Matter (1993), anticipated a profound social and intellectual upheaval around sex, sexuality, gender norms, and power. Like many readers of my generation, I was introduced to Butler’s work just as these changes began to accelerate, and her ideas became part of mainstream discourse. In recent years, Butler has turned her insights about norms and exceptions, the psychic life of power, and the politics of resistance toward political ethics. In December Butler and I discussed her latest book, The Force of Nonviolence, which explores “nonviolence” as a project capable not simply of disclosing structural and repressive forms of violence, but also of productively channeling the tensions of social life away from retribution and resentment toward a radical and redemptive notion of equality.

Judith Butler is arguably the most influential critical theorist of our era. Her early books, such as Gender Trouble (1990) and Bodies That Matter (1993), anticipated a profound social and intellectual upheaval around sex, sexuality, gender norms, and power. Like many readers of my generation, I was introduced to Butler’s work just as these changes began to accelerate, and her ideas became part of mainstream discourse. In recent years, Butler has turned her insights about norms and exceptions, the psychic life of power, and the politics of resistance toward political ethics. In December Butler and I discussed her latest book, The Force of Nonviolence, which explores “nonviolence” as a project capable not simply of disclosing structural and repressive forms of violence, but also of productively channeling the tensions of social life away from retribution and resentment toward a radical and redemptive notion of equality.