Rachel Madley in The Scientist:

Over the past decade, Americans have debated the best way to fix our broken healthcare system, one that allows 35,000 Americans to die each year because they don’t have health insurance and many more to forego necessary treatment or go bankrupt paying for care. This debate has intensified in recent months due to the increasing popularity of Medicare for All, a proposal to create a publicly funded single-payer health system, and its central role in the Democratic presidential race. First, let’s define what these terms mean: Single-payer Medicare for All would establish a public funding mechanism for healthcare that covers everyone for all medically necessary treatment, including dental, vision, and hearing care. This care would be free to everyone at the point of service, regardless of income, age, employment, or immigration status. Medicare for All changes how care is financed, but not how it’s delivered, thus patients would have free choice of any doctor or hospital. Besides the benefits to patients, Medicare for All would save approximately $500 billion annually in healthcare costs, according to one estimate, by, among other things, cutting out thousands of insurance middlemen and negotiating drug prices at the national level.

Over the past decade, Americans have debated the best way to fix our broken healthcare system, one that allows 35,000 Americans to die each year because they don’t have health insurance and many more to forego necessary treatment or go bankrupt paying for care. This debate has intensified in recent months due to the increasing popularity of Medicare for All, a proposal to create a publicly funded single-payer health system, and its central role in the Democratic presidential race. First, let’s define what these terms mean: Single-payer Medicare for All would establish a public funding mechanism for healthcare that covers everyone for all medically necessary treatment, including dental, vision, and hearing care. This care would be free to everyone at the point of service, regardless of income, age, employment, or immigration status. Medicare for All changes how care is financed, but not how it’s delivered, thus patients would have free choice of any doctor or hospital. Besides the benefits to patients, Medicare for All would save approximately $500 billion annually in healthcare costs, according to one estimate, by, among other things, cutting out thousands of insurance middlemen and negotiating drug prices at the national level.

Many health professionals support Medicare for All, including a majority of doctors and the largest nurses union in the US, as do a majority of registered voters in the US overall, but biomedical scientists have so far been silent. Yet they do have a stake in the outcome of healthcare reform. Medicare for All would increase the clinical data available for research and allow all patients to benefit from scientific innovation. Scratch the surface of our health system and we find that it hurts patients directly and indirectly—not just by keeping medical care out of reach, but by hindering the kind of medical research that drives innovation and benefits everyone. Today’s fractured system sequesters patient data within millions of different hospital and insurance databases, with little cross-institutional data sharing. When data are shared by multiple institutions, the coding and format are not standardized, making research on those cohorts difficult or impossible.

More here.

A “VISIONARY,” A “PROPHET,” A “MODERN-DAY LEONARDO”: Writers often resort to panegyrics when confronted with the eccentric, daunting intellect of Agnes Denes. Given the ambition of the octogenarian artist’s career, which spans fifty years and emerges from deep research into philosophy, mathematics, symbolic logic, and environmental science, it’s hard to fault them.

A “VISIONARY,” A “PROPHET,” A “MODERN-DAY LEONARDO”: Writers often resort to panegyrics when confronted with the eccentric, daunting intellect of Agnes Denes. Given the ambition of the octogenarian artist’s career, which spans fifty years and emerges from deep research into philosophy, mathematics, symbolic logic, and environmental science, it’s hard to fault them.

I

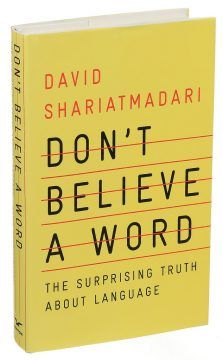

I It’s astonishing that humans are expected to make our way in the world with language alone. “To speak is an incomparable act / of faith,” the poet Craig Morgan Teicher has written. “What proof do we have / that when I say mouse, you do not think / of a stop sign?”

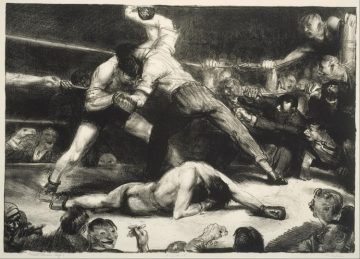

It’s astonishing that humans are expected to make our way in the world with language alone. “To speak is an incomparable act / of faith,” the poet Craig Morgan Teicher has written. “What proof do we have / that when I say mouse, you do not think / of a stop sign?” Gordon Marino teaches philosophy at St. Olaf College and curates the Hong Kierkegaard Library. He has spent decades writing about the existentialists. His passion for them did not begin in the classroom, though. After a failed relationship, with derailed careers in both boxing and academic philosophy, a young Marino strugged with suicidal thoughts. While waiting for a counseling session, he spotted a copy of Søren Kierkegaard’s Works of Love on a coffee-shop bookshelf. He opened it to a passage in which Kierkegaard criticizes a “conceited sagacity” that refuses to believe in love. Intrigued, Marino hid Works of Love under his coat on the way out the door. He credits the book with saving his life. “At the risk of seeming histrionic,” Marino writes, “there was a time when Kierkegaard grabbed me by the shoulder and pulled me back from the crossbeam and the rope.” In Kierkegaard and other existentialists, Marino found philosophers who wrote in the first person, took moods and emotions seriously, and kept up a staring contest with despair. While these eclectic thinkers often had qualms about the professoriate, they led Marino back to academic philosophy. He returned with an older conception of philosophy as a way of life and a pursuit of wisdom, a conception the existentialists helped renew and one that animates this compelling study of them.

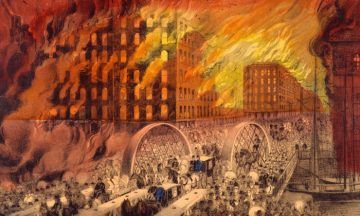

Gordon Marino teaches philosophy at St. Olaf College and curates the Hong Kierkegaard Library. He has spent decades writing about the existentialists. His passion for them did not begin in the classroom, though. After a failed relationship, with derailed careers in both boxing and academic philosophy, a young Marino strugged with suicidal thoughts. While waiting for a counseling session, he spotted a copy of Søren Kierkegaard’s Works of Love on a coffee-shop bookshelf. He opened it to a passage in which Kierkegaard criticizes a “conceited sagacity” that refuses to believe in love. Intrigued, Marino hid Works of Love under his coat on the way out the door. He credits the book with saving his life. “At the risk of seeming histrionic,” Marino writes, “there was a time when Kierkegaard grabbed me by the shoulder and pulled me back from the crossbeam and the rope.” In Kierkegaard and other existentialists, Marino found philosophers who wrote in the first person, took moods and emotions seriously, and kept up a staring contest with despair. While these eclectic thinkers often had qualms about the professoriate, they led Marino back to academic philosophy. He returned with an older conception of philosophy as a way of life and a pursuit of wisdom, a conception the existentialists helped renew and one that animates this compelling study of them. Called shikaakwa by the Miami-Illinois tribe for the skunky smell of the wild-onion that grew on the banks of Lake Michigan, “Chicago” is a French transcription of the earlier name for the area. Founded in 1833, with an initial population of 350, before the fire, it is said, Chicago’s streets curved around the Lake Michigan waterfront and followed the course of the Chicago River and a network of cattle paths lain over Native American migration routes. In contrast to the organic form of the city associated with the early settlers, modern Chicago would be organized as a grid, with address numbers (beginning in 1909) that could tell any pedestrian where they were in relationship to the central point (0,0) of State and Madison streets. According to plan, the modules of this new grid, great skyscrapers, grew up from the rubble like gigantic, up-stretched skeletons of cast iron and, later, steel. The grid, “a framework of spaced parallel bars” according to the Oxford American Dictionary, appears here as the image of an emerging modernity.

Called shikaakwa by the Miami-Illinois tribe for the skunky smell of the wild-onion that grew on the banks of Lake Michigan, “Chicago” is a French transcription of the earlier name for the area. Founded in 1833, with an initial population of 350, before the fire, it is said, Chicago’s streets curved around the Lake Michigan waterfront and followed the course of the Chicago River and a network of cattle paths lain over Native American migration routes. In contrast to the organic form of the city associated with the early settlers, modern Chicago would be organized as a grid, with address numbers (beginning in 1909) that could tell any pedestrian where they were in relationship to the central point (0,0) of State and Madison streets. According to plan, the modules of this new grid, great skyscrapers, grew up from the rubble like gigantic, up-stretched skeletons of cast iron and, later, steel. The grid, “a framework of spaced parallel bars” according to the Oxford American Dictionary, appears here as the image of an emerging modernity. Democracy is hard work. If it is to function well, citizens must do a lot of thinking and talking about politics. But democracy is demanding in another way as well. It requires us to maintain a peculiar moral posture toward our fellow citizens. We must acknowledge that they’re our equals and thus entitled to an equal say, even when their views are severely misguided. It seems a lot to ask.

Democracy is hard work. If it is to function well, citizens must do a lot of thinking and talking about politics. But democracy is demanding in another way as well. It requires us to maintain a peculiar moral posture toward our fellow citizens. We must acknowledge that they’re our equals and thus entitled to an equal say, even when their views are severely misguided. It seems a lot to ask. To search for Polanyi’s intellectual and political roots means coming into contact with a bewilderingly febrile left-wing intellectual milieu that appears to have little bearing on our present. However promising the current moment may seem with a self-described “democratic socialist” coming tantalizingly close to winning the Democratic Party’s presidential nomination, Gareth Dale’s new biography offers us a bracing reminder of a far richer world of socialist activity that once existed in much of the West. Debates over early-20th-century Hungarian socialism; the strategic plans of “Red Vienna”; the reformist 1961 platform of the Soviet Communist Party: These questions obsessed Polanyi and his contemporaries to a degree that seems almost inconceivable now and certainly residing in a sobering distance to our own immediate lives. Polanyi’s political activism and intellectual work were implicated in the widest questions debated on the left. The son of wealthy Hungarian Jews, he emerged as part of the “Great Generation” of Hungarian artists and intellectuals in Budapest at around the turn of the 20th century. John von Neumann, the mathematician, and Béla Bartók, the composer, were his contemporaries; so were the sociologist Karl Mannheim and the Marxist theoretician and literary critic György Lukács. Polanyi’s brother, Michael, became a philosopher of science, who for many years was better known than Karl.

To search for Polanyi’s intellectual and political roots means coming into contact with a bewilderingly febrile left-wing intellectual milieu that appears to have little bearing on our present. However promising the current moment may seem with a self-described “democratic socialist” coming tantalizingly close to winning the Democratic Party’s presidential nomination, Gareth Dale’s new biography offers us a bracing reminder of a far richer world of socialist activity that once existed in much of the West. Debates over early-20th-century Hungarian socialism; the strategic plans of “Red Vienna”; the reformist 1961 platform of the Soviet Communist Party: These questions obsessed Polanyi and his contemporaries to a degree that seems almost inconceivable now and certainly residing in a sobering distance to our own immediate lives. Polanyi’s political activism and intellectual work were implicated in the widest questions debated on the left. The son of wealthy Hungarian Jews, he emerged as part of the “Great Generation” of Hungarian artists and intellectuals in Budapest at around the turn of the 20th century. John von Neumann, the mathematician, and Béla Bartók, the composer, were his contemporaries; so were the sociologist Karl Mannheim and the Marxist theoretician and literary critic György Lukács. Polanyi’s brother, Michael, became a philosopher of science, who for many years was better known than Karl.

Over the past decade, Americans have debated the best way to fix our broken healthcare system, one that allows

Over the past decade, Americans have debated the best way to fix our broken healthcare system, one that allows  Boris Orman, who worked at a bakery, provides a typical example. In mid-1937, even as the whirlwind of Stalin’s purges surged across the country, Orman shared the following anekdot (joke) with a colleague over tea in the bakery cafeteria:

Boris Orman, who worked at a bakery, provides a typical example. In mid-1937, even as the whirlwind of Stalin’s purges surged across the country, Orman shared the following anekdot (joke) with a colleague over tea in the bakery cafeteria: One of the most famous vehicles in literature is coming to the Smithsonian’s

One of the most famous vehicles in literature is coming to the Smithsonian’s  When I was a Jewish kid growing up in suburban Los Angeles, we thought being Jewish meant supporting Israel.

When I was a Jewish kid growing up in suburban Los Angeles, we thought being Jewish meant supporting Israel. This work attending to the fullness of creation has revealed astounding complexity. As we walk through the forest, we notice plants and animals around us, but often we literally miss the forest’s interconnections for the trees. The greatest part of its biodiversity lies below ground, where thousands upon thousands of species of worms, arthropods, and insects live, each hosting a different bacterial community in its gut. We used to think of soil as a test tube full of chemicals, but now know that it’s a complex biological network; we are only beginning to understand its thousands of parts. These are “trophic” networks: who eats what and whom. The complexity goes far beyond predator and prey. Everything from a fallen evergreen needle to a tree is consumed, and the droppings of the consumers are consumed by yet other species through cycles upon cycles.

This work attending to the fullness of creation has revealed astounding complexity. As we walk through the forest, we notice plants and animals around us, but often we literally miss the forest’s interconnections for the trees. The greatest part of its biodiversity lies below ground, where thousands upon thousands of species of worms, arthropods, and insects live, each hosting a different bacterial community in its gut. We used to think of soil as a test tube full of chemicals, but now know that it’s a complex biological network; we are only beginning to understand its thousands of parts. These are “trophic” networks: who eats what and whom. The complexity goes far beyond predator and prey. Everything from a fallen evergreen needle to a tree is consumed, and the droppings of the consumers are consumed by yet other species through cycles upon cycles. Most science fiction takes place in a world in which “the future” has definitively arrived; the locomotive filmed by the Lumière brothers has finally burst through the screen. But in “Neuromancer” there was only a continuous arrival—an ongoing, alarming present. “Things aren’t different. Things are things,” an A.I. reports, after achieving a new level of consciousness. “You can’t let the little pricks generation-gap you,” one protagonist tells another, after an unnerving encounter with a teen-ager. In its uncertain sense of temporality—are we living in the future, or not?—“Neuromancer” was science fiction for the modern age. The novel’s influence has increased with time, establishing Gibson as an authority on the world to come.

Most science fiction takes place in a world in which “the future” has definitively arrived; the locomotive filmed by the Lumière brothers has finally burst through the screen. But in “Neuromancer” there was only a continuous arrival—an ongoing, alarming present. “Things aren’t different. Things are things,” an A.I. reports, after achieving a new level of consciousness. “You can’t let the little pricks generation-gap you,” one protagonist tells another, after an unnerving encounter with a teen-ager. In its uncertain sense of temporality—are we living in the future, or not?—“Neuromancer” was science fiction for the modern age. The novel’s influence has increased with time, establishing Gibson as an authority on the world to come.