by R. Passov

The economics of health insurance is of particular importance today. Health insurance has become a major issue of public policy. Some form of national health insurance is very likely to be enacted within the next few years. —Martin Feldstein 1

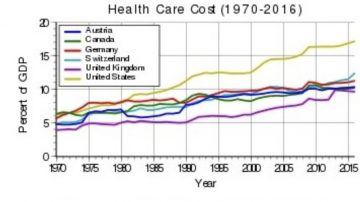

Fifty years ago, when healthcare expenditures were a mere 6% of US GDP, Martin Feldstein was afraid that the seemingly imminent adoption of some form of national health insurance would cause health care spending to grow unchecked.

Fifty years ago, when healthcare expenditures were a mere 6% of US GDP, Martin Feldstein was afraid that the seemingly imminent adoption of some form of national health insurance would cause health care spending to grow unchecked.

Turns out, like many economists, he was half right. While a truly national health scheme is still in the making, health care spending is now 18% of GDP, and growing.

Feldstein, known to his friends as Marty, was an interesting guy. For outstanding contributions to economics by an economist under 40, he was awarded the Bates Medal. He was President Reagan’s chief economic advisor, a long-time teacher at his alma matter, Harvard, and managed to retain the presidency and CEO titles at the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) from 1977 until his passing in 2019. (He stepped aside from 1982 to 1984 to serve Reagan.)

The NBER describes itself as a private, non-profit research organization and then adds that it has been the source for most leaders of the Council of Economic Advisors. The Council is in fact a government entity, constituting the chief economic advisors to the Office of the President, while the National Bureau, which sounds like it is, is not.

Anyway, fifty years ago, Feldstein took his economics – the ‘markets solve everything’ kind – and reached the following conclusion: The problem with healthcare is Health Insurance. Eliminate insurance wrote Feldstein, and market forces would reign in the runaway price of health services. Read more »

There are two very different essays I’ve been meaning to write, both of which equally merit the title of the present one.

There are two very different essays I’ve been meaning to write, both of which equally merit the title of the present one. At a recent group meeting, my postdoc raised a question: “Should we make our theoretical model more complex so that our explanation of the data will not appear too trivial?” I was surprised by this suggestion and felt obligated to explain why. “Simplicity is a virtue,” I said, “not a deficiency. Excessive mathematical gymnastics is used to show off in branches of theoretical physics that have scarce experimental data. But as physicists, we should seek the simplest explanation for our data. This is the lifeblood of physics and the appropriate measure of success.”

At a recent group meeting, my postdoc raised a question: “Should we make our theoretical model more complex so that our explanation of the data will not appear too trivial?” I was surprised by this suggestion and felt obligated to explain why. “Simplicity is a virtue,” I said, “not a deficiency. Excessive mathematical gymnastics is used to show off in branches of theoretical physics that have scarce experimental data. But as physicists, we should seek the simplest explanation for our data. This is the lifeblood of physics and the appropriate measure of success.” Early Friday morning, Qasem Soleimani, the head of the Iranian Revolutionary Guards Corps Quds Force, was

Early Friday morning, Qasem Soleimani, the head of the Iranian Revolutionary Guards Corps Quds Force, was  The story of Don Quixote never gets old. First published (Book One, that is) in 1605, Cervantes’s novel continually makes the list of the greatest books of all time, being the second most translated after the Bible. In 2002, the Norwegian Academy of Science and Letters asked a hundred authors across the world to name their choice for “best novel” of all time: Cervantes won in a landslide. Considered by many people to be “the first modern novel”, it is a story of a man’s search for truth. It is also hilariously funny. I was not surprised to learn that it is one of the most requested books by the inmates at Guantánamo.

The story of Don Quixote never gets old. First published (Book One, that is) in 1605, Cervantes’s novel continually makes the list of the greatest books of all time, being the second most translated after the Bible. In 2002, the Norwegian Academy of Science and Letters asked a hundred authors across the world to name their choice for “best novel” of all time: Cervantes won in a landslide. Considered by many people to be “the first modern novel”, it is a story of a man’s search for truth. It is also hilariously funny. I was not surprised to learn that it is one of the most requested books by the inmates at Guantánamo. My mother had green eyes. Black hair. Her name was Marie Augustine Adeline Legrand. She was born a peasant, daughter of farmers, near Dunkirk. She had one sister and seven brothers. She went to teachers college, on a scholarship, and she taught in Dunkirk. The day after an inspection, the inspector who had visited her class asked for her hand in marriage. Love at first sight. They got married and left for Indochina. Between 1900 and 1903. A sort of commitment, adventure, a sort of desire, too, not for fortune but for success. They left like heroes, pioneers, they visited the schools in oxcarts, they brought everything, quills, paper, ink. They had succumbed to the posters of the era urging, as if they were soldiers: “Enlist.”

My mother had green eyes. Black hair. Her name was Marie Augustine Adeline Legrand. She was born a peasant, daughter of farmers, near Dunkirk. She had one sister and seven brothers. She went to teachers college, on a scholarship, and she taught in Dunkirk. The day after an inspection, the inspector who had visited her class asked for her hand in marriage. Love at first sight. They got married and left for Indochina. Between 1900 and 1903. A sort of commitment, adventure, a sort of desire, too, not for fortune but for success. They left like heroes, pioneers, they visited the schools in oxcarts, they brought everything, quills, paper, ink. They had succumbed to the posters of the era urging, as if they were soldiers: “Enlist.” Nadira was living in Bahawalpur, in Pakistan. One day, she saw a cat on the window ledge of her room. It was looking into the room in a disquieting way, and she told the servant to get rid of the cat. He misunderstood and killed the poor creature. Not long after this, in a laundry basket near the window, Nadira found a tiny kitten who was so young that its eyes were still closed. She understood then that the poor creature that had been so casually killed was the mother of the little kitten, who was probably the last of the litter. She thought she should adopt him. The kitten slept in her bed, with Nadira and her two children. He received every attention that Nadira could think of. She knew very little about animals, and almost nothing about cats. She must have made mistakes, but the kitten, later the cat, repaid the devotion with extraordinary love. The cat appeared to know when Nadira was going to come back to the house. It just turned up, and it was an infallible sign that in a day or two Nadira herself would return. This happy relationship lasted for seven or eight years. Nadira decided then to leave the city and go and live in the desert. She took the cat with her, not knowing that a cat cannot easily change where it lives: all the extraordinary knowledge in its head, of friends and enemies and hiding places, built up over time, has to do with a particular place. A cat in a new setting is half helpless. So it turned out here.

Nadira was living in Bahawalpur, in Pakistan. One day, she saw a cat on the window ledge of her room. It was looking into the room in a disquieting way, and she told the servant to get rid of the cat. He misunderstood and killed the poor creature. Not long after this, in a laundry basket near the window, Nadira found a tiny kitten who was so young that its eyes were still closed. She understood then that the poor creature that had been so casually killed was the mother of the little kitten, who was probably the last of the litter. She thought she should adopt him. The kitten slept in her bed, with Nadira and her two children. He received every attention that Nadira could think of. She knew very little about animals, and almost nothing about cats. She must have made mistakes, but the kitten, later the cat, repaid the devotion with extraordinary love. The cat appeared to know when Nadira was going to come back to the house. It just turned up, and it was an infallible sign that in a day or two Nadira herself would return. This happy relationship lasted for seven or eight years. Nadira decided then to leave the city and go and live in the desert. She took the cat with her, not knowing that a cat cannot easily change where it lives: all the extraordinary knowledge in its head, of friends and enemies and hiding places, built up over time, has to do with a particular place. A cat in a new setting is half helpless. So it turned out here. Jeremy Bernstein in Inference:

Jeremy Bernstein in Inference: Adam Shatz over at the NYRB:

Adam Shatz over at the NYRB: C

C At a global financial services firm we worked with, a longtime customer accidentally submitted the same application file to two offices. Though the employees who reviewed the file were supposed to follow the same guidelines—and thus arrive at similar outcomes—the separate offices returned very different quotes. Taken aback, the customer gave the business to a competitor. From the point of view of the firm, employees in the same role should have been interchangeable, but in this case they were not. Unfortunately, this is a common problem.

At a global financial services firm we worked with, a longtime customer accidentally submitted the same application file to two offices. Though the employees who reviewed the file were supposed to follow the same guidelines—and thus arrive at similar outcomes—the separate offices returned very different quotes. Taken aback, the customer gave the business to a competitor. From the point of view of the firm, employees in the same role should have been interchangeable, but in this case they were not. Unfortunately, this is a common problem. Antonia Malchik in Aeon:

Antonia Malchik in Aeon: