William Foster in Nature:

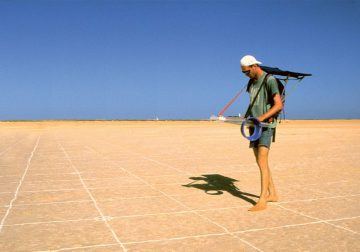

The fear of getting lost and being unable to find our way home is woven into the stories we hear as children: it can haunt us for years. Humanity’s navigational skills are poor and increasingly rarely used, leaving us to view feats of animal navigation with a mixture of envy and admiration. How do Atlantic salmon find their way back to the streams where they were born, after up to three years at sea? How do Arctic terns find their breeding sites in the far north after excursions of more than 70,000 kilometres to the Antarctic? Desert Navigator is the story of how a tiny ant (Cataglyphis spp.) became the ideal model organism for the study of animal navigation. It begins 50 years ago in a vast Saharan salt pan, where a lone, shiny black ant caught the eye of neuroethologist Rüdiger Wehner as it scuttled across the sand. Eventually, it discovered the corpse of a large fly, gripped it firmly in its mandibles, and then performed the manoeuvre that launched Wehner’s field of research.

The fear of getting lost and being unable to find our way home is woven into the stories we hear as children: it can haunt us for years. Humanity’s navigational skills are poor and increasingly rarely used, leaving us to view feats of animal navigation with a mixture of envy and admiration. How do Atlantic salmon find their way back to the streams where they were born, after up to three years at sea? How do Arctic terns find their breeding sites in the far north after excursions of more than 70,000 kilometres to the Antarctic? Desert Navigator is the story of how a tiny ant (Cataglyphis spp.) became the ideal model organism for the study of animal navigation. It begins 50 years ago in a vast Saharan salt pan, where a lone, shiny black ant caught the eye of neuroethologist Rüdiger Wehner as it scuttled across the sand. Eventually, it discovered the corpse of a large fly, gripped it firmly in its mandibles, and then performed the manoeuvre that launched Wehner’s field of research.

The ant set off in a straight line, crossing more than 100 metres of the barren ground to disappear into an inconspicuous hole — the entrance to its underground colony. The only plausible explanation is that the ant knew all along exactly where it was in relation to its home nest. But how does Cataglyphis manage this, with a minute brain and no mobile phone?

Wehner unspools the answer over the book’s seven chapters, describing the astonishing subtlety, intricacy and diversity of the techniques used both by the ants in finding their way home and by researchers in discovering how they do it. The ants plot their compass direction using patterns of polarized light and gradients of colour and light intensity in the sky, along with the position of the Sun, backed up by cues from Earth’s magnetic field and the wind direction. They know where they are by counting the steps they have taken and keeping track of the direction they were following at the time. They can memorize panoramic ‘snapshots’ of landmarks, such as boulders, around their goals. Somehow, their brains integrate all this information so that their foraging journeys can be optimally organized.

More here.