Ian Leslie in New Statesman America:

The night before I met Malcolm Gladwell, I went to see him speak at the Royal Festival Hall on London’s South Bank. The gig was sold out: as the young and diverse crowd filtered in, and the Specials played over the PA, I reflected on how unusual it is for a writer to fill so many seats, especially one with no creed to preach or secret to sell. People were not coming to sit at the feet of a guru. They were here to enjoy themselves. Gladwell, a strip of a man in jeans and sneakers, sauntered on stage, took his place behind a lectern and began telling a story from his new book, Talking To Strangers. Within two minutes he swerved off into a story about how he got the story, which involved him mistaking a call from a legendary CIA agent for one from Barack Obama. It doesn’t always come across in his writing, but Gladwell is funny. At the South Bank his words flowed and fizzed with vocal energy; he used his voice like an instrument, at times lowering it suggestively (“I mean I can’t tell you what Barack and I talked about…”), at others leaping high up in his range to register incredulity (“I’ve been at dinner parties with the super-rich. All they talk about is tax!”). His pauses and pay-offs were perfectly judged.

The night before I met Malcolm Gladwell, I went to see him speak at the Royal Festival Hall on London’s South Bank. The gig was sold out: as the young and diverse crowd filtered in, and the Specials played over the PA, I reflected on how unusual it is for a writer to fill so many seats, especially one with no creed to preach or secret to sell. People were not coming to sit at the feet of a guru. They were here to enjoy themselves. Gladwell, a strip of a man in jeans and sneakers, sauntered on stage, took his place behind a lectern and began telling a story from his new book, Talking To Strangers. Within two minutes he swerved off into a story about how he got the story, which involved him mistaking a call from a legendary CIA agent for one from Barack Obama. It doesn’t always come across in his writing, but Gladwell is funny. At the South Bank his words flowed and fizzed with vocal energy; he used his voice like an instrument, at times lowering it suggestively (“I mean I can’t tell you what Barack and I talked about…”), at others leaping high up in his range to register incredulity (“I’ve been at dinner parties with the super-rich. All they talk about is tax!”). His pauses and pay-offs were perfectly judged.

He was interviewed on stage by the journalist Afua Hirsch. It transpired that they both have a white father and a black mother. Gladwell had a theory about this, based on his observation that until recently, it was unusual for the female half of a mixed-race couple to be white. But then, Gladwell had a theory about everything. Over the course of the evening he expounded on policing, schools, sport, prison, why rich people don’t know how to enjoy being rich, and much more. Some theories were carefully weighed, others were riffs intended to elicit a gasp or a laugh. Even as Hirsch was wrapping up the Q&A, Gladwell interjected to ask why it always seems necessary to take questions from every part of the auditorium. “When you walked in here you had this identity,” he said, addressing the hall: “Say, British, white, female. But in the last 45 minutes, you’ve acquired this new one: stalls left. And suddenly it seems like a monstrous injustice that nobody from your side has been picked.”

For nearly 20 years, Gladwell has been America’s most important public intellectual. If the label seems incongruous, that might be because we think of public intellectuals as those such as Steven Pinker or Niall Ferguson: hommes sérieux who enjoy crushing those who disagree with them. Gladwell does not cultivate gravitas and doesn’t much mind if you disagree with him. He is an intellectual hedonist: his big idea is that ideas should be pleasurable. Rather than trying to persuade, he seeks to infect readers with his enthusiasms: isn’t this interesting? This ethos has birthed a whole publishing industry. It’s only a slight exaggeration to say that, without Gladwell, there would no Freakonomics, no Nudge, no TED Talks, no “Smart Thinking” section in Waterstones. For those who find the whole genre unbearably superficial, Gladwell is to blame.

More here.

It is nearly impossible to live in today’s world without having come across mention of the legendary Noam Chomsky. His work as a linguist, historian, political activist and philosopher, which spans nearly a century, has had an immeasurable impact on contemporary world views. Not only have his more than a hundred books become the basis for a vast milieu of modern thought, but he himself has become a widely admired public figure whose thoughtful take on current events is as crucial as ever in our increasingly hostile, chaotic sociopolitical climate.

It is nearly impossible to live in today’s world without having come across mention of the legendary Noam Chomsky. His work as a linguist, historian, political activist and philosopher, which spans nearly a century, has had an immeasurable impact on contemporary world views. Not only have his more than a hundred books become the basis for a vast milieu of modern thought, but he himself has become a widely admired public figure whose thoughtful take on current events is as crucial as ever in our increasingly hostile, chaotic sociopolitical climate.

W

W Hit certain crystalline materials with a jolt of electricity and they will change shape. Squeeze them and they will jolt you right back. Scientists have used these so-called piezoelectrics for decades in ultrasound medical imaging; the materials are so sensitive that they can pick up the motion of sound waves moving through tissue. Now, researchers have come up with a simple new way to make potent transparent piezoelectrics, which could lead to improved medical imagers, invisible robots, and touch screens that power themselves.

Hit certain crystalline materials with a jolt of electricity and they will change shape. Squeeze them and they will jolt you right back. Scientists have used these so-called piezoelectrics for decades in ultrasound medical imaging; the materials are so sensitive that they can pick up the motion of sound waves moving through tissue. Now, researchers have come up with a simple new way to make potent transparent piezoelectrics, which could lead to improved medical imagers, invisible robots, and touch screens that power themselves. According to the best-known telling of the tale, Hippasus, a Pythagorean of the fifth century b.c., was drowned in the sea by his fellow philosophers while on a fishing voyage. Hippasus had disclosed a secret that, if made public, risked destroying the credibility of his school’s commitment to a cosmos governed by perfect mathematical harmony: The relationship between a diagonal of a square and its side cannot be represented as a ratio — it is “irrational.” This legend sets the stage in

According to the best-known telling of the tale, Hippasus, a Pythagorean of the fifth century b.c., was drowned in the sea by his fellow philosophers while on a fishing voyage. Hippasus had disclosed a secret that, if made public, risked destroying the credibility of his school’s commitment to a cosmos governed by perfect mathematical harmony: The relationship between a diagonal of a square and its side cannot be represented as a ratio — it is “irrational.” This legend sets the stage in  Be warned. If the rise of the robots comes to pass, the apocalypse may be a more squelchy affair than science fiction writers have prepared us for.

Be warned. If the rise of the robots comes to pass, the apocalypse may be a more squelchy affair than science fiction writers have prepared us for. IMAGINE THAT ANDY WARHOL and Eva Hesse had a secret tryst in 1966 and Rachel Harrison was the love child that resulted. With its canny use of both Pop signs and funky materials, her rambunctious sculpture points to such an unlikely lineage. Smartly curated by Elisabeth Sussman and David Joselit, “Rachel Harrison Life Hack,” the midcareer survey of her work at the Whitney Museum of American Art, is roughly chronological: It guides us easily from an installation improvised out of cheap paneling, casual photographs, and canned peas in the mid-1990s to a large circle of totemic sculptures gathered for this show, with a few intense series of figure drawings and C-prints along the way. Despite the fact that Harrison is often taken to be a devil-may-care assemblage artist, the exhibition is almost spare, and this relative restraint has two welcome effects: We can learn the language of her work as it developed, and we can consider her image-object hybrids as sculptures, which also lets us reflect on the contemporary status of that medium vis-à-vis the other media sampled here. Early on, Harrison compressed the littered space of her initial installations into the tight juxtapositions of her composite objects, and thereby heightened the cultural contradictions that her pointed riffs on postwar art, mass media, and US politics call out.

IMAGINE THAT ANDY WARHOL and Eva Hesse had a secret tryst in 1966 and Rachel Harrison was the love child that resulted. With its canny use of both Pop signs and funky materials, her rambunctious sculpture points to such an unlikely lineage. Smartly curated by Elisabeth Sussman and David Joselit, “Rachel Harrison Life Hack,” the midcareer survey of her work at the Whitney Museum of American Art, is roughly chronological: It guides us easily from an installation improvised out of cheap paneling, casual photographs, and canned peas in the mid-1990s to a large circle of totemic sculptures gathered for this show, with a few intense series of figure drawings and C-prints along the way. Despite the fact that Harrison is often taken to be a devil-may-care assemblage artist, the exhibition is almost spare, and this relative restraint has two welcome effects: We can learn the language of her work as it developed, and we can consider her image-object hybrids as sculptures, which also lets us reflect on the contemporary status of that medium vis-à-vis the other media sampled here. Early on, Harrison compressed the littered space of her initial installations into the tight juxtapositions of her composite objects, and thereby heightened the cultural contradictions that her pointed riffs on postwar art, mass media, and US politics call out. The Ascent of Affect turns on the contention that what is most at stake across various intellectual debates, from the humanities to neurosciences, is the conceptual status and normative value of the idea of intentionality, that is, of the idea that there is a relationship between “the mind” and things, or properties, or states of affairs of some sort. The question of how to understand the “aboutness” of mental states the long-standing theme of philosophical debates about intentionality.

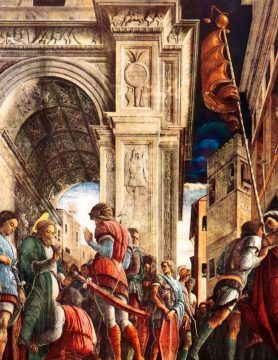

The Ascent of Affect turns on the contention that what is most at stake across various intellectual debates, from the humanities to neurosciences, is the conceptual status and normative value of the idea of intentionality, that is, of the idea that there is a relationship between “the mind” and things, or properties, or states of affairs of some sort. The question of how to understand the “aboutness” of mental states the long-standing theme of philosophical debates about intentionality. The frescos in Assisi heralded a revolution both in representation and in metaphysical leaning whose consequences for Western art, philosophy, and science can hardly be underestimated. It is here, too, that we may locate the seed of the video gaming industry. Bacon was giving voice to an emerging view that the God of Judeo-Christianity had created the world according to geometric laws and that Truth was thus to be found in geometrical representation. This Christian mathematicism would culminate in the scientific achievements of Galileo and Newton four centuries later and continues to resonate in contemporary physicists’ quest for a hyper-dimensional “Theory of Everything.” In The Heritage of Giotto’s Geometry, Edgerton argues that the idea that the world exists as a geometric void—which is the foundation on which Galileo and Newton built the new physics and cosmology—was patterned into Western consciousness by three centuries of perspectival representation beginning with Bacon’s missive to Clement. Thus the scientific revolution was birthed in the visual revolution of geometric figuring.

The frescos in Assisi heralded a revolution both in representation and in metaphysical leaning whose consequences for Western art, philosophy, and science can hardly be underestimated. It is here, too, that we may locate the seed of the video gaming industry. Bacon was giving voice to an emerging view that the God of Judeo-Christianity had created the world according to geometric laws and that Truth was thus to be found in geometrical representation. This Christian mathematicism would culminate in the scientific achievements of Galileo and Newton four centuries later and continues to resonate in contemporary physicists’ quest for a hyper-dimensional “Theory of Everything.” In The Heritage of Giotto’s Geometry, Edgerton argues that the idea that the world exists as a geometric void—which is the foundation on which Galileo and Newton built the new physics and cosmology—was patterned into Western consciousness by three centuries of perspectival representation beginning with Bacon’s missive to Clement. Thus the scientific revolution was birthed in the visual revolution of geometric figuring. The night before I met Malcolm Gladwell, I went to see him speak at the Royal Festival Hall on London’s South Bank. The gig was sold out: as the young and diverse crowd filtered in, and the Specials played over the PA, I reflected on how unusual it is for a writer to fill so many seats, especially one with no creed to preach or secret to sell. People were not coming to sit at the feet of a guru. They were here to enjoy themselves. Gladwell, a strip of a man in jeans and sneakers, sauntered on stage, took his place behind a lectern and began telling a story from his new book, Talking To Strangers. Within two minutes he swerved off into a story about how he got the story, which involved him mistaking a call from a legendary CIA agent for one from Barack Obama. It doesn’t always come across in his writing, but Gladwell is funny. At the South Bank his words flowed and fizzed with vocal energy; he used his voice like an instrument, at times lowering it suggestively (“I mean I can’t tell you what Barack and I talked about…”), at others leaping high up in his range to register incredulity (“I’ve been at dinner parties with the super-rich. All they talk about is tax!”). His pauses and pay-offs were perfectly judged.

The night before I met Malcolm Gladwell, I went to see him speak at the Royal Festival Hall on London’s South Bank. The gig was sold out: as the young and diverse crowd filtered in, and the Specials played over the PA, I reflected on how unusual it is for a writer to fill so many seats, especially one with no creed to preach or secret to sell. People were not coming to sit at the feet of a guru. They were here to enjoy themselves. Gladwell, a strip of a man in jeans and sneakers, sauntered on stage, took his place behind a lectern and began telling a story from his new book, Talking To Strangers. Within two minutes he swerved off into a story about how he got the story, which involved him mistaking a call from a legendary CIA agent for one from Barack Obama. It doesn’t always come across in his writing, but Gladwell is funny. At the South Bank his words flowed and fizzed with vocal energy; he used his voice like an instrument, at times lowering it suggestively (“I mean I can’t tell you what Barack and I talked about…”), at others leaping high up in his range to register incredulity (“I’ve been at dinner parties with the super-rich. All they talk about is tax!”). His pauses and pay-offs were perfectly judged. The human genome contains billions of pieces of information and around 22,000 genes, but not all of it is, strictly speaking, human. Eight percent of our DNA consists of remnants of ancient viruses, and another 40 percent is made up of repetitive strings of genetic letters that is also thought to have a viral origin. Those extensive viral regions are much more than evolutionary relics: They may be deeply involved with a wide range of diseases including multiple sclerosis, hemophilia, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), along with certain types of dementia and cancer. For many years, biologists had little understanding of how that connection worked—so little that they came to refer to the viral part of our DNA as dark matter within the genome. “They just meant they didn’t know what it was or what it did,” explains Molly Gale Hammell, an associate professor at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory. It became evident that the virus-related sections of the genetic code do not participate in the normal construction and regulation of the body. But in that case, how do they contribute to disease?

The human genome contains billions of pieces of information and around 22,000 genes, but not all of it is, strictly speaking, human. Eight percent of our DNA consists of remnants of ancient viruses, and another 40 percent is made up of repetitive strings of genetic letters that is also thought to have a viral origin. Those extensive viral regions are much more than evolutionary relics: They may be deeply involved with a wide range of diseases including multiple sclerosis, hemophilia, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), along with certain types of dementia and cancer. For many years, biologists had little understanding of how that connection worked—so little that they came to refer to the viral part of our DNA as dark matter within the genome. “They just meant they didn’t know what it was or what it did,” explains Molly Gale Hammell, an associate professor at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory. It became evident that the virus-related sections of the genetic code do not participate in the normal construction and regulation of the body. But in that case, how do they contribute to disease?

I grew up in a house with very few books, but there was one that came with my family from Iran and never let me go: a slender, battered book of poetry my mother displayed on the mantle, next to photographs of our family and the country we’d been forced to flee. The cover showed a woman with kohl-lined eyes and bobbed hair, and the Persian script slanted upwards, as if in flight from the page. That book wasn’t an object or even an artifact but an atmosphere. Parting the pages released a sharp, acrid scent that was the very scent of Iran, which was also the scent of time, love, and loss.

I grew up in a house with very few books, but there was one that came with my family from Iran and never let me go: a slender, battered book of poetry my mother displayed on the mantle, next to photographs of our family and the country we’d been forced to flee. The cover showed a woman with kohl-lined eyes and bobbed hair, and the Persian script slanted upwards, as if in flight from the page. That book wasn’t an object or even an artifact but an atmosphere. Parting the pages released a sharp, acrid scent that was the very scent of Iran, which was also the scent of time, love, and loss. We are all alive, but “life” is something we struggle to understand. How do we distinguish a “living organism” from an emergent dynamical system like a hurricane, or a resource-consuming chemical reaction like a forest fire, or an information-processing system like a laptop computer? There is probably no one crisp set of criteria that delineates life from non-life, but it’s worth the exercise to think about what we really mean, especially as the quest to find life outside the confines of the Earth picks up steam. Sara Imari Walker planned to become a cosmologist before shifting her focus to astrobiology, and is now a leading researcher on the origin and nature of life. We talk about what life is and how to find it, with a special focus on the role played by information and computation in living beings.

We are all alive, but “life” is something we struggle to understand. How do we distinguish a “living organism” from an emergent dynamical system like a hurricane, or a resource-consuming chemical reaction like a forest fire, or an information-processing system like a laptop computer? There is probably no one crisp set of criteria that delineates life from non-life, but it’s worth the exercise to think about what we really mean, especially as the quest to find life outside the confines of the Earth picks up steam. Sara Imari Walker planned to become a cosmologist before shifting her focus to astrobiology, and is now a leading researcher on the origin and nature of life. We talk about what life is and how to find it, with a special focus on the role played by information and computation in living beings. Democracy can be frustrating; our hard-won right to participate in the task of collective self-government often results in disappointment and exasperation. What’s more, in the wake of a political defeat, democracy’s sole consolation is ‘continue working’; if you lose at the polls, you mustn’t resign or withdraw, but instead turn to the next election and begin anew. Citizenship takes persistence. And in both emotional and practical terms, that’s asking a lot.

Democracy can be frustrating; our hard-won right to participate in the task of collective self-government often results in disappointment and exasperation. What’s more, in the wake of a political defeat, democracy’s sole consolation is ‘continue working’; if you lose at the polls, you mustn’t resign or withdraw, but instead turn to the next election and begin anew. Citizenship takes persistence. And in both emotional and practical terms, that’s asking a lot.