by Mary Hrovat

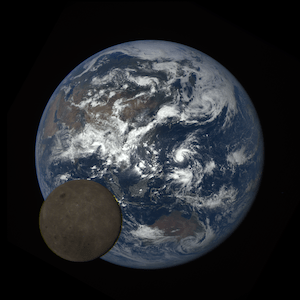

I think it was in the 1980s that I first saw t-shirts showing a drawing of a spiral galaxy with an arrow indicating “You are here.” They were amusing, and the image provides a bit of cosmic context. You may be here, looking at this screen, with your to-do list and personal problems and worries about the world, but you’re also here in the Orion arm of the Milky Way, about 25,000 light years from the center, in this solar system, on this planet.

One way to capture the most local part of your cosmic context is the 3D solar simulator at The Sky Live, which shows a simulated snapshot of the locations of all the planets relative to the sun at this moment. You can zoom in and out and add asteroids, near-Earth objects, and comets. You can also animate the simulation. At one week per second, you get a pretty good view of the tight circling of the inner planets, but the outer planets move at a very sedate pace. At one year per second, the inner planets move too quickly to follow easily, but the outer planets sweep along briskly.

Of course, you can also observe the solar system from the inside. One great way to broaden your horizons is to go out in the evening to see what other planets in the solar system are visible and to watch them moving along in their orbits over the weeks and months. There are a number of guides to what you can see on a clear night. Sky & Telescope provides a weekly update that tells you which planets will be visible, what phase the moon is in, and whether there will be any events such as eclipses or meteor showers. Space.com offers a monthly summary that covers a somewhat broader range of things to look for in the night sky, and EarthSky describes what you can see in the sky tonight.

In addition, space is not an unchanging backdrop but a place with its own weather (sort of) and events. Spaceweather.com posts news stories about solar activity, aurorae, meteor showers, fireball observations, and more. The sidebar on the left shows current data and images. Read more »

We find ourselves always in the middle of an experience. But it’s what we do next – how we characterize the experience – that lays down a host of important and almost subterranean conditions. Am I sitting in a chair, gazing out the dusty window into a world of sunlight, trees, and snow? Am I meditating on the nature of experience? Am I praying? Am I simply spacing out? Depending on which way I parse whatever the hell I’m up to, my experience shifts from something ineffable (or at any rate, not currently effed) to something meaningful and determinate, festooned with many other conversational hooks and openings: “enjoying nature”, “introspecting”, “conversing with God”, “resting”, “procrastinating”, and so on. Putting the experience into words tells me what to do with it next.

We find ourselves always in the middle of an experience. But it’s what we do next – how we characterize the experience – that lays down a host of important and almost subterranean conditions. Am I sitting in a chair, gazing out the dusty window into a world of sunlight, trees, and snow? Am I meditating on the nature of experience? Am I praying? Am I simply spacing out? Depending on which way I parse whatever the hell I’m up to, my experience shifts from something ineffable (or at any rate, not currently effed) to something meaningful and determinate, festooned with many other conversational hooks and openings: “enjoying nature”, “introspecting”, “conversing with God”, “resting”, “procrastinating”, and so on. Putting the experience into words tells me what to do with it next.

Forever is a long time.

Forever is a long time. I first met Roger Scruton almost 20 years ago at a symposium in Sweden. I admired the eloquence with which he could talk about Kant and the elegance of his writing on beauty. I learned from his conservatism, even as I disagreed with what he said. But although I got to know him quite well over the years, our relationship was always fraught. For there was another Roger Scruton, not the philosopher but the polemicist. For all his warmth and generosity, and for all the poise of his writing, his views were often ugly. “Whatever its defects,” Scruton wrote in his memoir

I first met Roger Scruton almost 20 years ago at a symposium in Sweden. I admired the eloquence with which he could talk about Kant and the elegance of his writing on beauty. I learned from his conservatism, even as I disagreed with what he said. But although I got to know him quite well over the years, our relationship was always fraught. For there was another Roger Scruton, not the philosopher but the polemicist. For all his warmth and generosity, and for all the poise of his writing, his views were often ugly. “Whatever its defects,” Scruton wrote in his memoir  TOURISTS VISITING

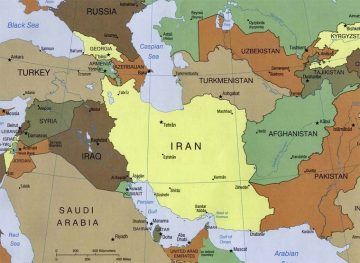

TOURISTS VISITING On September 24, 2019, in his UN address President Trump defended the United States’s economic sanctions against Iran by invoking language that has become so familiar to us we fail to hear its ruthless and genocidal resonances. After stating that it was his duty and priority to “defend America’s interests,” Trump cited “Iran’s blood-lust,” its “menacing behavior,” its “traffic in monstrous antisemitism,” and accused Iran of single-handedly destabilizing the Middle East. The use of abstract and degrading terminology to discuss Iran has a long history in American politics: in 1987, during a televised address in reference to the Iran–Contra Affair, Ronald Reagan innocently stated that “what began as a strategic opening to Iran deteriorated, in its implementation, into trading arms for hostages” (it’s important to note that Jimmy Carter had lost the reelection to Reagan because he was devoted to the Middle East Peace Process and unwilling, in his own words, to “wipe Iran off the map”); in 1989, George H.W. Bush claimed that “we can’t have normalized relations with a state that’s branded a terrorist state”; and, during his State of the Union address months after the ghastly and apocalyptic 9/11 attacks, George Bush stated that “Iran aggressively pursues weapons of mass destruction and exports terror,” and that “states like these [Iran, Iraq and North Korea] and their terrorist allies constitute an axis of evil arming to threaten the peace of the world by seeking weapons of mass destruction posing a grave and growing danger.” This appeal to nationalist discourse has served time and again to justify the imposition of American will over Iran.

On September 24, 2019, in his UN address President Trump defended the United States’s economic sanctions against Iran by invoking language that has become so familiar to us we fail to hear its ruthless and genocidal resonances. After stating that it was his duty and priority to “defend America’s interests,” Trump cited “Iran’s blood-lust,” its “menacing behavior,” its “traffic in monstrous antisemitism,” and accused Iran of single-handedly destabilizing the Middle East. The use of abstract and degrading terminology to discuss Iran has a long history in American politics: in 1987, during a televised address in reference to the Iran–Contra Affair, Ronald Reagan innocently stated that “what began as a strategic opening to Iran deteriorated, in its implementation, into trading arms for hostages” (it’s important to note that Jimmy Carter had lost the reelection to Reagan because he was devoted to the Middle East Peace Process and unwilling, in his own words, to “wipe Iran off the map”); in 1989, George H.W. Bush claimed that “we can’t have normalized relations with a state that’s branded a terrorist state”; and, during his State of the Union address months after the ghastly and apocalyptic 9/11 attacks, George Bush stated that “Iran aggressively pursues weapons of mass destruction and exports terror,” and that “states like these [Iran, Iraq and North Korea] and their terrorist allies constitute an axis of evil arming to threaten the peace of the world by seeking weapons of mass destruction posing a grave and growing danger.” This appeal to nationalist discourse has served time and again to justify the imposition of American will over Iran. The campus upheavals of the 1960s brought a wave of responses from the professoriate, but one in particular stood out. Written by two economists, James M. Buchanan and Nicos E. Devletoglou, Academia in Anarchy (Basic Books, 1970) opened with a law-and-order quote from Richard Nixon and was dedicated to “the taxpayer.” The authors explained that they wrote with “indignation” after observing the bombing of the UCLA economics department, where Buchanan taught, and the “groveling of the UCLA administrative authorities” to a “handful of revolutionary terrorists.”

The campus upheavals of the 1960s brought a wave of responses from the professoriate, but one in particular stood out. Written by two economists, James M. Buchanan and Nicos E. Devletoglou, Academia in Anarchy (Basic Books, 1970) opened with a law-and-order quote from Richard Nixon and was dedicated to “the taxpayer.” The authors explained that they wrote with “indignation” after observing the bombing of the UCLA economics department, where Buchanan taught, and the “groveling of the UCLA administrative authorities” to a “handful of revolutionary terrorists.” Nowadays, not many philosophers are prominent enough to get nicknames. In medieval times the practice was more popular. Every scholastic worth their salt had one: Bonaventure was the “seraphic doctor”, Aquinas the “angelic doctor”, Duns Scotus the “subtle doctor”, and so on. In the Islamic world, too, outstanding thinkers were honoured with such titles. Of these, none was more appropriate than al-shaykh al-raʾīs, which one might loosely translate as “the leading sage”. It was bestowed on Abū ʿAlī Ibn Sīnā (d.1037 AD), who was known to all those medieval scholastics by the Latinized name “Avicenna”. And not just known, but renowned. Avicenna is one of the few philosophers to have become a major influence on the development of a completely foreign philosophical culture. Once his works were translated into Latin he became second only to Aristotle as an inspiration for thirteenth-century medieval philosophy, and (thanks to his definitive medical summary the Canon, in Arabic Qānūn) second only to Galen as a source for medical knowledge in Europe.

Nowadays, not many philosophers are prominent enough to get nicknames. In medieval times the practice was more popular. Every scholastic worth their salt had one: Bonaventure was the “seraphic doctor”, Aquinas the “angelic doctor”, Duns Scotus the “subtle doctor”, and so on. In the Islamic world, too, outstanding thinkers were honoured with such titles. Of these, none was more appropriate than al-shaykh al-raʾīs, which one might loosely translate as “the leading sage”. It was bestowed on Abū ʿAlī Ibn Sīnā (d.1037 AD), who was known to all those medieval scholastics by the Latinized name “Avicenna”. And not just known, but renowned. Avicenna is one of the few philosophers to have become a major influence on the development of a completely foreign philosophical culture. Once his works were translated into Latin he became second only to Aristotle as an inspiration for thirteenth-century medieval philosophy, and (thanks to his definitive medical summary the Canon, in Arabic Qānūn) second only to Galen as a source for medical knowledge in Europe. When Wellcome Sanger Institute geneticist

When Wellcome Sanger Institute geneticist

A

A