Neo Matloga. Unknown Title. 2018.

Currently showing at Zeitz Museum, Cape Town.

by Rafaël Newman

I am employed two or three weekends a month as a minder or “Betreuer” at a treatment centre and halfway house for recovering drug addicts in Zurich. My duties include spending the night at the facility as the lone member of supervisory staff, eating meals with the clients, supervising their activities and accompanying their outings, taking urine samples and administering breathalyzer tests, distributing a variety of antidepressants and other prescription meds, and joining them for sessions of meditation and self-led group therapy.

Our clients typically come from the Swiss middle and working class, are predominantly white and “European”, and have in common with other addicts of my acquaintance a marked tendency to egocentrism and either a concomitant failure of empathy or, in reaction to the affective over-sensitivity that has come to be associated with addiction (particularly in the case of celebrity overdose victims such as Philip Seymour Hoffman), a self-protective closing of the border between self and other, whether by chemical, behavioral, or neurotic means.

Among my unspoken responsibilities as a minder, therefore, and in line with the principles of the self-help program that serve the center as an unofficial “philosophy”, is the performance of a living example: of empathy in action; of open-mindedness regarding others and their sensibilities or “struggles”; of humility and the will to serve, rather than simply to use, exploit, and consume. And as a consequence, the recovering addicts in my charge are, implicitly, to learn how to belong to a group rather than to go it alone, as they have been wont to do in active addiction. Read more »

Michael Caligiuri, a renowned physician-scientist is the President of City of Hope National Medical Center, and Deana and Steve Campbell Physician-in-Chief Distinguished Chair. He directed The Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center for 14 years prior as well as being the chief executive officer of The James Cancer Hospital and Solove Research Institute for 10 years. Caligiuri’s research focuses on the development and activation of human natural killer cells and their modulation for the treatment of leukemia, myeloma, and glioblastoma. He is a fellow and the immediate past president of the American Association for Cancer Research and has been elected to the National Academy of Medicine (NAM), one of the highest honors in the fields of health and medicine.

Azra Raza, author of the forthcoming book The First Cell: And the Human Costs of Pursuing Cancer to the Last, oncologist and professor of medicine at Columbia University, and 3QD editor, decided to speak to more than 20 leading cancer investigators and ask each of them the same five questions listed below. She videotaped the interviews and over the next months we will be posting them here one at a time each Monday. Please keep in mind that Azra and the rest of us at 3QD neither endorse nor oppose any of the answers given by the researchers as part of this project. Their views are their own. One can browse all previous interviews here.

1. We were treating acute myeloid leukemia (AML) with 7+3 (7 days of the drug cytosine arabinoside and 3 days of daunomycin) in 1977. We are still doing the same in 2019. What is the best way forward to change it by 2028?

2. There are 3.5 million papers on cancer, 135,000 in 2017 alone. There is a staggering disconnect between great scientific insights and translation to improved therapy. What are we doing wrong?

3. The fact that children respond to the same treatment better than adults seems to suggest that the cancer biology is different and also that the host is different. Since most cancers increase with age, even having good therapy may not matter as the host is decrepit. Solution?

4. You have great knowledge and experience in the field. If you were given limitless resources to plan a cure for cancer, what will you do?

5. Offering patients with advanced stage non-curable cancer, palliative but toxic treatments is a service or disservice in the current therapeutic landscape?

by Eric J. Weiner

Caring for myself is not self-indulgence, it is self-preservation, and that is an act of political warfare. —Audre Lorde

As I write this introduction, I struggle against becoming overwhelmed by too many things: The mass shootings that occur on a regular basis; the daily gun-related murder and maiming that occur throughout the country everyday; the normalization of white supremacy/nationalism; the poverty you can see in the eyes of children in shelters and on the street; a twittering billionaire president who mugs for the cameras of “the enemy of the people” as children are concentrated in “camps” at the southern border; the increase in crimes against immigrants, African Americans, Jews, Muslims, women, and gay people; the gouging prices of life saving drugs like insulin; and the smugness of those in congress who summer far from the death and chaos, muttering to the press about mental illness, second amendment rights, the “free” market, cultural deficits, and anything else that might distract from the callousness and cynicism that drives what poses for public policy these days. And I could go on.

But I know that if I am overwhelmed then I will not have the energy to resist, talk back, confront, fight, struggle, reflect, transform, teach, and renew. In this essay, I will discuss what it means to develop what I am calling a praxis of pleasure as both a strategy and tactic of resistance. As a tactic, a la Michel de Certeau, it is a practice of reclaiming a modicum of power within an established geography of inequitable power relationships. As a strategy, it is a guide toward living well so that we may rise to fight another day. Read more »

by Akim Reinhardt

Smacked my head on the pavement while jogging across campus in the rain. Had my hands on my stomach, holding documents in place underneath my shirt to keep them dry. So when my foot went out after skipping over a puddle, I couldn’t get my front paws down in time to brace my fall as I corkscrewed through the air, landing on my hip and shoulder, and whiplashing my head downward. Consequently I don’t have the brain power to crank out 2,000 fresh words. So here’s a dated piece about Baby Boomer navel gazing and ressentiment.

Smacked my head on the pavement while jogging across campus in the rain. Had my hands on my stomach, holding documents in place underneath my shirt to keep them dry. So when my foot went out after skipping over a puddle, I couldn’t get my front paws down in time to brace my fall as I corkscrewed through the air, landing on my hip and shoulder, and whiplashing my head downward. Consequently I don’t have the brain power to crank out 2,000 fresh words. So here’s a dated piece about Baby Boomer navel gazing and ressentiment.

Perhaps I should just skip a week instead of peddling an old, cranky number that previously had not found the light of day. That would probably be the prudent, and certainly reasonable course. But vanity urges me onward. I have a bit of a streak running here at 3QD and don’t want to break it just cause I cracked my noggin. Alas, for better or worse then, I move forward by looking backwards.

*

Ugh. Bob Dylan.

Even though we’re well into the 21st century and half the Baby Boomers are collecting Social Security, they’re still determined to thumb their noses at their parents. Even the Swedish ones, apparently. So Bob Dylan gets a Nobel Prize in Literature.

I told you, daaaaaaaaad! My music is art toooo! Seeee?

You know what? You’re dad’s dead. Grow up. Find a new battle to fight. Go argue with your grandkids or something.

Bob Dylan. Jesus.

The guy plagiarized substantial portions of the only prose book he ever wrote, his 2005 memoir. You’d think that right there would disqualify a writer from winning the world’s most prestigious lifetime literary award. But this is the Age of Truthiness, so I guess all bets are off. Read more »

by Brooks Riley

by Bill Murray

Thirty years ago this week two million people joined hands forming a human chain across 676 kilometers of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania. Known as the Baltic Way, the visually arresting stunt was a cinematic cri de coeur for freedom.

Thirty years ago this week two million people joined hands forming a human chain across 676 kilometers of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania. Known as the Baltic Way, the visually arresting stunt was a cinematic cri de coeur for freedom.

In time freedom was theirs. The Russian military fled, sometimes trashing their barracks and looting along the way the way. As a measure of the state in which the Soviet Union left the Baltics, still now, thirty years on it takes around seven hours to travel by train between Tallinn and Riga, the capitals of two European countries separated by scarcely 200 miles. Imagine.

The Estonian and Latvian railways have finally co-ordinated their timetables, but you still have to walk across the platform to change trains at the border. By contrast, the drive takes perhaps four and a half hours, and, as both are now Schengen countries, your vehicle breezes through the abandoned border post without slowing down.

Much of that drive, after the tidy Estonian border town of Parnu, takes you south along the coast of the Gulf of Riga. Estonia and Latvia are lovely during this early bit of Baltic autumn, grasses with full summer growth waving in fields skirting Baltic shores. Read more »

by Sarah Firisen

I’ve just come back from a lovely vacation in Ireland. We did a lot of driving and usually had the radio on, often to RTE, the state run station (the equivalent to the BBC in the UK). At least once an hour an advertisement would come on reminding people that they need to get a TV license, which costs 160 Euros, $177 a year. I grew up in the UK, where a license is 154.50 sterling, $187 a year, and remember the ads when I was a child that warned of the TV detector van coming around and catching people who hadn’t paid their license. Of course, that was in the days of very obvious exterior antennas on houses. When TV licenses were first issued in the UK after the second world war, they funded the single BBC channel. Even when I was a child, there were only 3 channels, then when I was a teen 4, and two of those were the BBC. In the UK today, a license is needed for any device that is “installed or used” for “receiving a television programme at the same time (or virtually the same time) as it is received by members of the public”. In Ireland, as the many ads I heard made clear, the license is for a physical TV, regardless of what it’s used for, including gaming or streaming YouTube videos. In the UK, you don’t need a license if you watch anything else on your TV, including using catch-up devices and players for BBC shows, except if you use the BBC iPlayer services, but you do need a license if you watch live TV or use the BBC iPlayer on any device.

I’ve just come back from a lovely vacation in Ireland. We did a lot of driving and usually had the radio on, often to RTE, the state run station (the equivalent to the BBC in the UK). At least once an hour an advertisement would come on reminding people that they need to get a TV license, which costs 160 Euros, $177 a year. I grew up in the UK, where a license is 154.50 sterling, $187 a year, and remember the ads when I was a child that warned of the TV detector van coming around and catching people who hadn’t paid their license. Of course, that was in the days of very obvious exterior antennas on houses. When TV licenses were first issued in the UK after the second world war, they funded the single BBC channel. Even when I was a child, there were only 3 channels, then when I was a teen 4, and two of those were the BBC. In the UK today, a license is needed for any device that is “installed or used” for “receiving a television programme at the same time (or virtually the same time) as it is received by members of the public”. In Ireland, as the many ads I heard made clear, the license is for a physical TV, regardless of what it’s used for, including gaming or streaming YouTube videos. In the UK, you don’t need a license if you watch anything else on your TV, including using catch-up devices and players for BBC shows, except if you use the BBC iPlayer services, but you do need a license if you watch live TV or use the BBC iPlayer on any device.

Listening to these repeated ads in Ireland, it struck me how regressive this license charge is. Reading up on the differences in the UK, their rules seem fairer at least. On my return, I read that Ireland is actually changing its licensing rules in the future and that “The Government is to scrap the current licence fee and replace it with a charge that will hit virtually every Irish home, regardless of whether a television set is present…It will mean that anyone with a laptop, a tablet or a smartphone at home will be liable to pay.”

I’m not really debating the virtue or utility of such licenses. There’s clearly a valid debate about the need for state owned TV and radio stations in this day and age, but that’s not my point to debate here either. Rather, my thoughts are about government’s ability to keep pace with technological changes. Read more »

Self-portrait in reflection on the entrance doors of the showroom of famous chandelier-maker, Faustig, in Brixen, South Tyrol, in October of 2014.

by John Schwenkler

The community of philosophers is mourning the loss of Barry Stroud, one of the great philosophers of the past half-century, who died on Friday, August 9 of brain cancer. Stroud earned his B.A. from the University of Toronto and his Ph.D. from Harvard University. From 1961 he taught at the University of California, Berkeley, where I knew him during my time as a graduate student there.

The community of philosophers is mourning the loss of Barry Stroud, one of the great philosophers of the past half-century, who died on Friday, August 9 of brain cancer. Stroud earned his B.A. from the University of Toronto and his Ph.D. from Harvard University. From 1961 he taught at the University of California, Berkeley, where I knew him during my time as a graduate student there.

Stroud’s important paper of 1968, “Transcendental Arguments,” followed Immanuel Kant in distinguishing two sorts of question that a philosopher can raise about the concepts human beings use in thinking about ourselves and our world. The first, which Kant associates with John Locke, is the question of fact that concerns which concepts we do have and how we came to possess them. To explore our concepts in this way is to engage in what Kant, in his Critique of Pure Reason, called a “physiology of human understanding.” It is to give a causal account of how our minds came to be the way they are—an important project, but not one that is distinctively philosophical, since empirical disciplines such as psychology, sociology, and anthropology also take it up.

Kant’s other way of reflecting on human concepts, which is the one he undertakes in the first Critique, raises instead a question of right. This question asks, given that we have the concepts we do and have come to possess them in whatever way we did, whether we really are justified in possessing those concepts and using them to think about things. It is a question of whether our ways of thinking allow us to have an objective grasp of reality rather than a merely subjective conception of how things are. Read more »

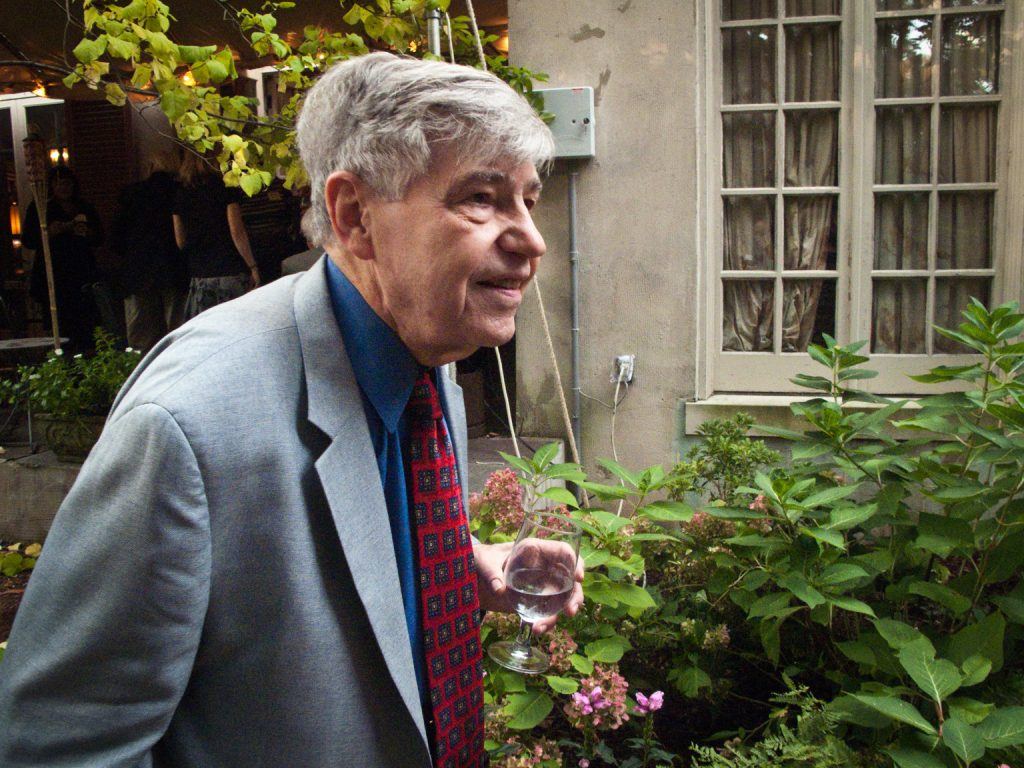

While cruising the web on the evening of July 22, 2019, I learned that Dick Macksey had died earlier in the day. He was a legend at Johns Hopkins University, had been for years – a prodigious polymath who speaks who knows how many languages, a tireless teacher, a genial host, and an indefatigable conversationalist who owns more books than the Library of Alexandria, though only a few of them are quite that old. Everyone had spoken of the legend for decades, and Everyone is now retelling it.

The thing about legends is that they are based in fact, but the amplification serves to create distance from facts behind the legend.

I had worked with Macksey for seven years between 1966, the spring of my freshman year at Johns Hopkins, and the fall 1973, when I went to SUNY Buffalo to get a doctorate in English literature. I have had occasional contact with him since then, both in person and over the phone. I knew the legend of course. But I also glimpsed the man. Read more »

Richard Hughes Gibson in The Hedgehog Review:

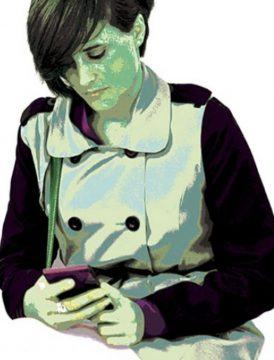

Complaints about the decline of friendship have become a staple of conversation in our digital times. But before we dismiss them as simply byproducts of generational turnover, consider the evidence that something more substantial is going on. The very language of friendship, for instance, is changing right before our eyes. Facebook has convinced us that “friend” can be a verb, often deployed in the imperative mood (“Friend me on…”). Apps have elevated the number of friends above the quality of friendship, displaying the tallies for onlookers to admire, one’s (envious) friends especially. As more than one observer has noted, “Friends used to be counted on; now they are counted up.” The digital age has even spawned a new species of friend, its title still evolving: Online friend? Internet friend? E-friend? These are friends whose acquaintances we make, and whose company we almost exclusively keep, in digital domains, and advice columns warn of the challenges of meeting such friends “IRL”—that is, in real life.

Complaints about the decline of friendship have become a staple of conversation in our digital times. But before we dismiss them as simply byproducts of generational turnover, consider the evidence that something more substantial is going on. The very language of friendship, for instance, is changing right before our eyes. Facebook has convinced us that “friend” can be a verb, often deployed in the imperative mood (“Friend me on…”). Apps have elevated the number of friends above the quality of friendship, displaying the tallies for onlookers to admire, one’s (envious) friends especially. As more than one observer has noted, “Friends used to be counted on; now they are counted up.” The digital age has even spawned a new species of friend, its title still evolving: Online friend? Internet friend? E-friend? These are friends whose acquaintances we make, and whose company we almost exclusively keep, in digital domains, and advice columns warn of the challenges of meeting such friends “IRL”—that is, in real life.

Concerns about technology’s impact on friendship have been issuing from the academy as well.

More here.

Alex Trembath in OneZero:

Earlier this month, Chipotle CEO Brian Niccol explained that his company’s restaurants won’t offer plant-based meat like Beyond Meat and Impossible Foods “because of the processing.”

Earlier this month, Chipotle CEO Brian Niccol explained that his company’s restaurants won’t offer plant-based meat like Beyond Meat and Impossible Foods “because of the processing.”

It’s a strange position for Chipotle to take. First, it is not obvious to me why mixing and manipulating plants, as Impossible and Beyond do, make fake meat any more processed than the other ingredients served at Chipotle. I enjoy Chipotle from time to time. I have enjoyed their white flour tortillas. I have enjoyed their cheese, made using genetically modified enzymes and refilled throughout the day from bulk packages of a pre-shredded mixture. I have enjoyed their offerings of Coca-Cola, made from corn syrup, and Diet Coke, flavored with aspartame. I have enjoyed their sous vide beef. I have enjoyed their gypsum-infused soy tofu sofritas, which you could also call plant-based meat.

You get the idea.

More here.

Benjamin Hein in Taxis:

Thousands of years ago, hunters tossed aside their spears and began cultivating the fruits of the earth. The arrival of agricultural society, we have long been told, marked a turning point in human history. Cultivating grains generated an abundance of food, liberating our species from its struggle with scarcity and its primitive, nomadic existence. In the first great bread basket societies such as Mesopotamia, Egypt, and Rome, humanity flourished. Well-fed and secure, we began devoting ourselves to the finer things in life, like building pyramids and exploring the universe.

Thousands of years ago, hunters tossed aside their spears and began cultivating the fruits of the earth. The arrival of agricultural society, we have long been told, marked a turning point in human history. Cultivating grains generated an abundance of food, liberating our species from its struggle with scarcity and its primitive, nomadic existence. In the first great bread basket societies such as Mesopotamia, Egypt, and Rome, humanity flourished. Well-fed and secure, we began devoting ourselves to the finer things in life, like building pyramids and exploring the universe.

That is an inspiring story about human progress, but also wrong in many ways, argues Yale political scientist James Scott in his latest book Against the Grain: A Deep History of the Earliest States. Contrary to popular belief, nomadism actually persisted for millennia and indeed predominated as the leading form of social organization for most of human history. Only around 1600 CE did grain-based sedentism begin to supersede nomadic forms of subsistence around the world. One of the reasons why this has been forgotten is our skewed reading of the source record. “If you built, monumentally, in stone and left your debris conveniently in a single place, you were likely to be ‘discovered’ and to dominate the pages of ancient history,” writes Scott. But “if you were hunter-gatherers or nomads, however numerous, spreading your biodegradable trash thinly across the landscape, you were likely to vanish entirely from the archaeological record.”

Another, perhaps more important, problem with the grain narrative is that it relies on a misleading assumption about human nature: that homo sapiens supposedly wishes nothing more in life than to settle down and munch on bread, couscous, or rice. Scott begs to differ.

More here.

Adam Shatz in The New Yorker:

Adam Shatz in The New Yorker:

n 1951, the novelist Richard Wright explained his decision to settle in Paris after the war. “It is because I love freedom,” he wrote, in an essay titled “I Choose Exile,” “and I tell you frankly that there is more freedom in one square block of Paris than in the entire United States of America!” Few of the black Americans who made Paris their home from the nineteen-twenties to the civil-rights era would have quarreled with Wright’s claim. For novelists such as Wright, Chester Himes, and James Baldwin, for artists and musicians such as Josephine Baker, Sidney Bechet, and Beauford Delaney, Paris offered a sanctuary from segregation and discrimination, as well as an escape from American puritanism—an experience as far as possible from the “damaged life” that Theodor Adorno considered to be characteristic of exile. You could stroll down the street with a white lover or spouse without being jeered at; you could check into a hotel or rent an apartment wherever you wished so long as you could pay for it. You could enjoy, in short, something like normalcy.

Baldwin, who moved to Paris in 1948, two years after Wright, embraced the gift at first but came to distrust it. While blacks “armed with American passports” were rarely the target of racism, Africans and Algerians from France’s overseas colonies, he realized, were not so lucky. In his essay “Alas, Poor Richard,” published in 1961, just after Wright’s death, Baldwin accused his mentor of celebrating Paris as a “city of refuge” while remaining silent about France’s oppressive treatment of its colonial subjects: “It did not seem worthwhile to me to have fled the native fantasy only to embrace a foreign one.”

More here.

Carol Strickland in The Christian Science Monitor:

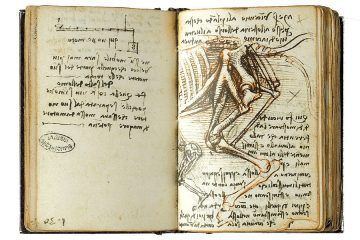

As someone who appreciates Leonardo da Vinci’s painting skills, I’ve long marveled at how crowds rush past his most sublime painting, “The Virgin and Child with Saint Anne,” to line up in front of the “Mona Lisa” at the Louvre Museum in Paris. The art critic in me wants to say, “Wait! Look at this one. See the poses of entwining bodies and gazes, the melting regard of the mother for her child, the translucent folds of cloth, the baby’s chubby legs.” It’s a perfect combination of humanity and divinity. Now, at the 500th anniversary of Leonardo’s death, scholars, art lovers, and the public are taking a far-reaching look at his career. Exhibitions in Italy and England, as well as the largest-ever survey of his work that opens at the Louvre this fall, are celebrating the master’s achievements not only in art but also in science.

As someone who appreciates Leonardo da Vinci’s painting skills, I’ve long marveled at how crowds rush past his most sublime painting, “The Virgin and Child with Saint Anne,” to line up in front of the “Mona Lisa” at the Louvre Museum in Paris. The art critic in me wants to say, “Wait! Look at this one. See the poses of entwining bodies and gazes, the melting regard of the mother for her child, the translucent folds of cloth, the baby’s chubby legs.” It’s a perfect combination of humanity and divinity. Now, at the 500th anniversary of Leonardo’s death, scholars, art lovers, and the public are taking a far-reaching look at his career. Exhibitions in Italy and England, as well as the largest-ever survey of his work that opens at the Louvre this fall, are celebrating the master’s achievements not only in art but also in science.

One of those exhibitions, of Leonardo’s drawings, is attracting multitudes to the Queen’s Gallery at Buckingham Palace in London. “Leonardo da Vinci: A Life in Drawing” displays the full range of Leonardo’s elastic mind at work. The main impression conveyed by “A Life in Drawing” is of a life in process, a man and mind on a continuous learning curve, endlessly observing, studying, thinking, reflecting. The drawings – more than the finished paintings – show him improvising and experimenting, much more than just recording reality.

More here.

Daniel Everett in Aeon:

[I intend] to make a philosophy like that of Aristotle, that is to say, to outline a theory so comprehensive that, for a long time to come, the entire work of human reason, in philosophy of every school and kind, in mathematics, in psychology, in physical science, in history, in sociology and in whatever other department there may be, shall appear as the filling up of its details.

C S Peirce, Collected Papers (1931-58)

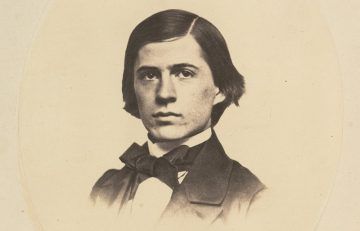

The roll of scientists born in the 19th century is as impressive as any century in history. Names such as Albert Einstein, Nikola Tesla, George Washington Carver, Alfred North Whitehead, Louis Agassiz, Benjamin Peirce, Leo Szilard, Edwin Hubble, Katharine Blodgett, Thomas Edison, Gerty Cori, Maria Mitchell, Annie Jump Cannon and Norbert Wiener created a legacy of knowledge and scientific method that fuels our modern lives. Which of these, though, was ‘the best’? Remarkably, in the brilliant light of these names, there was in fact a scientist who surpassed all others in sheer intellectual virtuosity. Charles Sanders Peirce (1839-1914), pronounced ‘purse’, was a solitary eccentric working in the town of Milford, Pennsylvania, isolated from any intellectual centre. Although many of his contemporaries shared the view that Peirce was a genius of historic proportions, he is little-known today. His current obscurity belies the prediction of the German mathematician Ernst Schröder, who said that Peirce’s ‘fame [will] shine like that of Leibniz or Aristotle into all the thousands of years to come’.

The roll of scientists born in the 19th century is as impressive as any century in history. Names such as Albert Einstein, Nikola Tesla, George Washington Carver, Alfred North Whitehead, Louis Agassiz, Benjamin Peirce, Leo Szilard, Edwin Hubble, Katharine Blodgett, Thomas Edison, Gerty Cori, Maria Mitchell, Annie Jump Cannon and Norbert Wiener created a legacy of knowledge and scientific method that fuels our modern lives. Which of these, though, was ‘the best’? Remarkably, in the brilliant light of these names, there was in fact a scientist who surpassed all others in sheer intellectual virtuosity. Charles Sanders Peirce (1839-1914), pronounced ‘purse’, was a solitary eccentric working in the town of Milford, Pennsylvania, isolated from any intellectual centre. Although many of his contemporaries shared the view that Peirce was a genius of historic proportions, he is little-known today. His current obscurity belies the prediction of the German mathematician Ernst Schröder, who said that Peirce’s ‘fame [will] shine like that of Leibniz or Aristotle into all the thousands of years to come’.

…The importance and range of Peirce’s contributions to science, mathematics and philosophy can be appreciated partially by recognising that many of the most important advances in philosophy and science over the past 150 years originated with Peirce: the development of mathematical logic (before and arguably better eventually than Gottlob Frege); the development of semiotics (before and arguably better than Ferdinand de Saussure); the philosophical school of pragmatism (before and arguably better than William James); the modern development of phenomenology (independently of and arguably superior to Edmund Husserl); and the invention of universal grammar with the property of recursion (before and arguably better than Noam Chomsky; though, for Peirce, universal grammar – a term he first used in 1865 – was the set of constraints on signs, with syntax playing a lesser role).

More here.

Like a sailor practicing knots in the darkness,

like a warrior sharpening his blade in the lull of battle,

like a blind man searching out the figure of a sleeping lover

the mind surges and eddies

through the concourses of the terminal

with its station and concessions

of bottled water sandwiches,

dot.com billboards trumpeting instant riches,

another gourmet coffee at the cappuccino bar,

grande decaf half-skim latte,

seeking to delimit its appetites and hungers,

as even Money magazine wonders

how much is enough?

Like one returned home after years of hard travel

I call out in greeting to my familiars—

Avarice, trusted and faithful retainer,

Extravagance, mi compañero,

Greed, my old friend, my bodyguard, my brother.

by Campbell McGrath

from Nouns & Verbs

Harper Collins, 2019