A Greeting on the Trail

Turning fifty, at last I come to understand,

belatedly, unexpectedly, and quite suddenly,

that poetry is not going to save anybody’s life,

least of all my own. Nonetheless I choose to believe

the journey is not a descent but a climb,

as when, in a forest of golden-green morning sunlight,

one sees another hiker on the trail, who calls out,

where are you bound, friend, to the valley or the mountaintop?

Many things—seaweed, pollen, attention—drift.

News of the universe’s origin infiltrates atom by atom

the oxygenated envelope of the atmosphere.

My sense of purpose vectors away on rash currents

like the buoys I find tossed on the beach after a storm,

cork bobbers torn from old crab traps.

And what befalls the woebegotten crabs,

caged and forgotten at the bottom of the sea?

Are the labors to which we are summoned by dreams

so different from the tasks to which the sunlight of reality

enslaves us? One tires of niceties. We sleep now

surrounded by books, books piled in heaps

by the bedside, stacked along the walls of the room.

Let dust accrue on their spines and colophons,

let their ragged towers rise and wobble.

Of course the Chinese poets were familiar with all this,

T’ao Ch’ien, Hsieh Ling-yün, Po Chü-i,

masterful sophisticates adopting common accents

for their nostalgic drinking songs and laments

to age and temple ruins, imperial avarice,

autumn leaves caught in a tumbling stream.

Read more »

The life of the Polish Jewish author Bruno Schulz was, by pedestrian measures, a small one. It ended prematurely in 1942, when he was murdered in the street at the age of 50 by a Gestapo officer, and it was almost entirely confined to his provincial hometown of Drohobycz. Schulz drew compulsively, and in his brooding sketches crammed big-headed figures into cramped frames and rooms with low, clutching ceilings. Schulz himself was short and hunched. In photographs, he glowers. “He was small, strange, chimerical, focused, intense, almost feverish,” a friend, the Polish novelist Witold Gombrowicz, recalled in a diary entry. His fiction, too, was small and strange. Schulz’s surviving output consists of just two collections of short fiction, some letters, a few essays, and a handful of stray stories. His longest work spans about 150 pages.

The life of the Polish Jewish author Bruno Schulz was, by pedestrian measures, a small one. It ended prematurely in 1942, when he was murdered in the street at the age of 50 by a Gestapo officer, and it was almost entirely confined to his provincial hometown of Drohobycz. Schulz drew compulsively, and in his brooding sketches crammed big-headed figures into cramped frames and rooms with low, clutching ceilings. Schulz himself was short and hunched. In photographs, he glowers. “He was small, strange, chimerical, focused, intense, almost feverish,” a friend, the Polish novelist Witold Gombrowicz, recalled in a diary entry. His fiction, too, was small and strange. Schulz’s surviving output consists of just two collections of short fiction, some letters, a few essays, and a handful of stray stories. His longest work spans about 150 pages. Compared to humans, whales and elephants can have hundreds of times the number of cells — and have similarly long natural lifespans — but their cells mutate, become cancerous, and kill them less frequently. This quirk of nature, which the ACE team is studying, is called Peto’s Paradox, named for

Compared to humans, whales and elephants can have hundreds of times the number of cells — and have similarly long natural lifespans — but their cells mutate, become cancerous, and kill them less frequently. This quirk of nature, which the ACE team is studying, is called Peto’s Paradox, named for  Well, we now have a solid record of what Trump has said and done. And it fits few modern templates exactly. He is no Pinochet nor Hitler, no Nixon nor Clinton. His emergence as a

Well, we now have a solid record of what Trump has said and done. And it fits few modern templates exactly. He is no Pinochet nor Hitler, no Nixon nor Clinton. His emergence as a  The current champion of heavyweight cinema, who vacillates between gallery and traditional cinematic presentation, must be the Chinese documentarian Wang Bing, who broke out internationally with his first film Tie Xi Qu: West of the Tracks (2003) and has subsequently produced the fourteen-hour Crude Oil (2008)—premiered as an installation at the 2008 International Film Festival Rotterdam—as well as the nearly nine-hour Dead Souls (2018). Andrew Chan, writing for Film Comment in 2016, distilled the role of duration in Wang’s work, writing, “Wang’s durational extremes do not just carry with them the weight of history and the inertia of the present; they also suggest that we as viewers might repay the gift of his subjects’ nakedness with our own sustained submission.” Chan is writing specifically about Wang’s 2013 ‘Til Madness Do Us Part, a nearly four-hour film that takes place almost entirely inside a dismal, crumbling mental institution doing double-duty as a lock-up for political undesirables. “Time in these films does not embrace, it provokes,” Chan continues, with further reference to West of the Tracks. “It’s felt as sacrifice and labor. And the aim is to make us earn, as if such a thing were possible, the right to lay eyes on humiliations that are at once collectively borne and unbearably private.”

The current champion of heavyweight cinema, who vacillates between gallery and traditional cinematic presentation, must be the Chinese documentarian Wang Bing, who broke out internationally with his first film Tie Xi Qu: West of the Tracks (2003) and has subsequently produced the fourteen-hour Crude Oil (2008)—premiered as an installation at the 2008 International Film Festival Rotterdam—as well as the nearly nine-hour Dead Souls (2018). Andrew Chan, writing for Film Comment in 2016, distilled the role of duration in Wang’s work, writing, “Wang’s durational extremes do not just carry with them the weight of history and the inertia of the present; they also suggest that we as viewers might repay the gift of his subjects’ nakedness with our own sustained submission.” Chan is writing specifically about Wang’s 2013 ‘Til Madness Do Us Part, a nearly four-hour film that takes place almost entirely inside a dismal, crumbling mental institution doing double-duty as a lock-up for political undesirables. “Time in these films does not embrace, it provokes,” Chan continues, with further reference to West of the Tracks. “It’s felt as sacrifice and labor. And the aim is to make us earn, as if such a thing were possible, the right to lay eyes on humiliations that are at once collectively borne and unbearably private.”

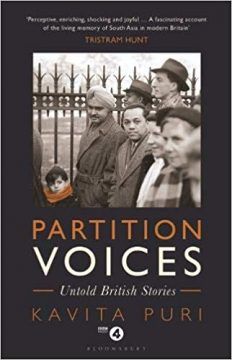

A Britain without the South Asian British is now almost unthinkable. With a few exceptions – farming, fishing and the armed forces spring to mind – there are few sectors of UK life where the descendants of South Asian immigrants are not prominent. Kavita Puri, for example, author of the harrowing Partition Voices, is a distinguished broadcaster whose father, Ravi, relocated from Delhi to Middlesbrough in 1959. The Puri family had lived originally in Lahore. But while the Puris were Hindu, the majority of Lahoris were Muslim. Under the terms of the 1947 partition plan, Lahore became part of Pakistan. The Puri family, in order to survive the carnage that ensued, had to flee across the border to the new Indian state, ending up in Delhi.

A Britain without the South Asian British is now almost unthinkable. With a few exceptions – farming, fishing and the armed forces spring to mind – there are few sectors of UK life where the descendants of South Asian immigrants are not prominent. Kavita Puri, for example, author of the harrowing Partition Voices, is a distinguished broadcaster whose father, Ravi, relocated from Delhi to Middlesbrough in 1959. The Puri family had lived originally in Lahore. But while the Puris were Hindu, the majority of Lahoris were Muslim. Under the terms of the 1947 partition plan, Lahore became part of Pakistan. The Puri family, in order to survive the carnage that ensued, had to flee across the border to the new Indian state, ending up in Delhi. It matters that the first patients were identical twins. Nancy and Barbara Lowry were six years old, dark-eyed and dark-haired, with eyebrow-skimming bangs. Sometime in the spring of 1960, Nancy fell ill. Her blood counts began to fall; her pediatricians noted that she was anemic. A biopsy revealed that she had a condition called aplastic anemia, a form of bone-marrow failure. The marrow produces blood cells, which need regular replenishing, and Nancy’s was rapidly shutting down. The origins of this illness are often mysterious, but in its typical form the spaces where young blood cells are supposed to be formed gradually fill up with globules of white fat. Barbara, just as mysteriously, was completely healthy. The Lowrys lived in Tacoma, a leafy, rain-slicked city near Seattle. At Seattle’s University of Washington hospital, where Nancy was being treated, the doctors had no clue what to do next. So they called a physician-scientist named E. Donnall Thomas, at the hospital in Cooperstown, New York, asking for help.

It matters that the first patients were identical twins. Nancy and Barbara Lowry were six years old, dark-eyed and dark-haired, with eyebrow-skimming bangs. Sometime in the spring of 1960, Nancy fell ill. Her blood counts began to fall; her pediatricians noted that she was anemic. A biopsy revealed that she had a condition called aplastic anemia, a form of bone-marrow failure. The marrow produces blood cells, which need regular replenishing, and Nancy’s was rapidly shutting down. The origins of this illness are often mysterious, but in its typical form the spaces where young blood cells are supposed to be formed gradually fill up with globules of white fat. Barbara, just as mysteriously, was completely healthy. The Lowrys lived in Tacoma, a leafy, rain-slicked city near Seattle. At Seattle’s University of Washington hospital, where Nancy was being treated, the doctors had no clue what to do next. So they called a physician-scientist named E. Donnall Thomas, at the hospital in Cooperstown, New York, asking for help. Kary Mullis, whose invention of the polymerase chain reaction technique earned him the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1993, died of pneumonia on August 7, according to

Kary Mullis, whose invention of the polymerase chain reaction technique earned him the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1993, died of pneumonia on August 7, according to

I live and work in two different cities; on the commute, I continuously ask my phone for advice: When’s the next train? Must I take the bus, or can I afford to walk and still make the day’s first meeting? I let my phone direct me to places to eat and things to see, and I’ll admit that for almost any question, my first impulse is to ask the internet for advice.

I live and work in two different cities; on the commute, I continuously ask my phone for advice: When’s the next train? Must I take the bus, or can I afford to walk and still make the day’s first meeting? I let my phone direct me to places to eat and things to see, and I’ll admit that for almost any question, my first impulse is to ask the internet for advice.

To follow the popular discourse about the gender wage gap in the United States is to confront perpetual confusion. It is a confusion created at least in part by pronouncements of the type many of us have heard: “Women are paid only 82 cents for every dollar men earn! It is high time for women to earn equal pay for equal work!” Two sentences, each true standing alone, but in juxtaposition creating the impression that the

To follow the popular discourse about the gender wage gap in the United States is to confront perpetual confusion. It is a confusion created at least in part by pronouncements of the type many of us have heard: “Women are paid only 82 cents for every dollar men earn! It is high time for women to earn equal pay for equal work!” Two sentences, each true standing alone, but in juxtaposition creating the impression that the  On occasions, while meandering the various English countryside and woodland paths, I have been pleasantly surprised to come across anglers. I have met fishermen dangling their lines in either a pond in some remote corner of the low-lying areas, or wading in water and casting a line down through the waters of a gently flowing river.

On occasions, while meandering the various English countryside and woodland paths, I have been pleasantly surprised to come across anglers. I have met fishermen dangling their lines in either a pond in some remote corner of the low-lying areas, or wading in water and casting a line down through the waters of a gently flowing river.