Conor Friedersdorf in The Atlantic:

I concur that Trump, as surely as Lee Atwater, marshals racist tropes. But I doubt the last claim: “Instrumental racists” believe that voters will perhaps respond only to racism. And I doubt that voters, in fact, respond only to racism. Something distinct and deeper is at work. This deeper force explains nearly all of Trump’s most odious and irresponsible comments, not just the racist ones. It helps explain why so many conservatives and Republicans were caught off guard by Trump’s rise and the resonance of his bigotry. And it helps clarify what the left sees and doesn’t see about racism. Once leftists understand it, they will find it easier to defeat the identitarian right.

I concur that Trump, as surely as Lee Atwater, marshals racist tropes. But I doubt the last claim: “Instrumental racists” believe that voters will perhaps respond only to racism. And I doubt that voters, in fact, respond only to racism. Something distinct and deeper is at work. This deeper force explains nearly all of Trump’s most odious and irresponsible comments, not just the racist ones. It helps explain why so many conservatives and Republicans were caught off guard by Trump’s rise and the resonance of his bigotry. And it helps clarify what the left sees and doesn’t see about racism. Once leftists understand it, they will find it easier to defeat the identitarian right.

No one better anticipated today’s societal divisions than the political psychologist Karen Stenner, author of the 2005 book The Authoritarian Dynamic. The book built on research literature that distinguishes between “authoritarians,” who prize what Stenner calls “oneness and sameness” so much so that they are prone to support coercion to effect it, and “libertarians,” who not only defend but affirmatively prize diversity and difference. (Those labels are not to be conflated with the popular definitions of the terms.)

More here.

There are many mysteries surrounding quantum mechanics. To me, the biggest mysteries are why physicists haven’t yet agreed on a complete understanding of the theory, and even more why they mostly seem content not to try. This puzzling attitude has historical roots that go back to the Bohr-Einstein debates. Adam Becker, in his book What Is Real?, looks at this history, and discusses how physicists have shied away from the foundations of quantum mechanics in the subsequent years. We discuss why this has been the case, and talk about some of the stubborn iconoclasts who insisted on thinking about it anyway.

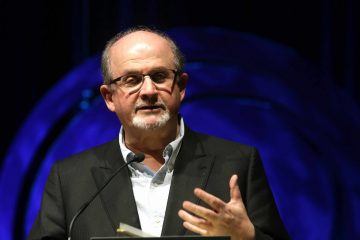

There are many mysteries surrounding quantum mechanics. To me, the biggest mysteries are why physicists haven’t yet agreed on a complete understanding of the theory, and even more why they mostly seem content not to try. This puzzling attitude has historical roots that go back to the Bohr-Einstein debates. Adam Becker, in his book What Is Real?, looks at this history, and discusses how physicists have shied away from the foundations of quantum mechanics in the subsequent years. We discuss why this has been the case, and talk about some of the stubborn iconoclasts who insisted on thinking about it anyway. The novel’s protagonists are Indian-born Muslims. Saladin is a voiceover artist and an immigrant from Bombay to London whose shame about his Indian-ness and desire to be anglicised form the backdrop to a complex interrogation of what it means to be rootless and how migrants in a globalised world can find a sense of identity. Gibreel, meanwhile, is a legend of the Bombay movie scene whose recent health crisis has led him to lose his faith and travel to London to be with the woman he loves, Alleluia Cone. Famous for portraying Hindu gods on screen, Gibreel’s newfound archangelic nature sorely tests his mind—a newly godless man condemned to act as God’s (or is that Satan’s?) right hand on earth.

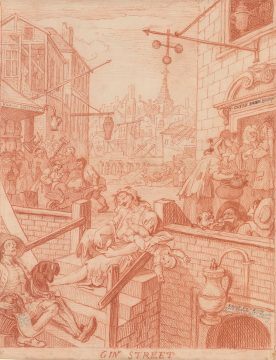

The novel’s protagonists are Indian-born Muslims. Saladin is a voiceover artist and an immigrant from Bombay to London whose shame about his Indian-ness and desire to be anglicised form the backdrop to a complex interrogation of what it means to be rootless and how migrants in a globalised world can find a sense of identity. Gibreel, meanwhile, is a legend of the Bombay movie scene whose recent health crisis has led him to lose his faith and travel to London to be with the woman he loves, Alleluia Cone. Famous for portraying Hindu gods on screen, Gibreel’s newfound archangelic nature sorely tests his mind—a newly godless man condemned to act as God’s (or is that Satan’s?) right hand on earth. “Cruelty and Humor” may be the subtitle of the Hogarth exhibition on display at the Morgan Library through September 22, but “Beer and Gin” would be more fitting. In the early eighteenth century, the British government (amid heightened tensions with France) instituted a policy to promote gin, a traditionally British drink, at the expense of French brandy. The policy proved too effective: by 1743, the average Brit was—in an intoxicated and nationalist frenzy—drinking 2.2 gallons each year. A satirist, agitator, and, in the words of David Bindman, “self-consciously English artist,” William Hogarth (1697–1764) employed his work in the hopes of chilling the “Gin Craze” of the 1750s.

“Cruelty and Humor” may be the subtitle of the Hogarth exhibition on display at the Morgan Library through September 22, but “Beer and Gin” would be more fitting. In the early eighteenth century, the British government (amid heightened tensions with France) instituted a policy to promote gin, a traditionally British drink, at the expense of French brandy. The policy proved too effective: by 1743, the average Brit was—in an intoxicated and nationalist frenzy—drinking 2.2 gallons each year. A satirist, agitator, and, in the words of David Bindman, “self-consciously English artist,” William Hogarth (1697–1764) employed his work in the hopes of chilling the “Gin Craze” of the 1750s. The notion of Anne Frank’s diary as a source of redemption, or at least consolation, received a further boost from the American stage play, written by two Hollywood screenwriters, Frances Goodrich and Albert Hackett, in 1955. The famous last words in the play are taken from a diary entry on July 15, 1944: “In spite of everything, I still believe that people are really good at heart”. Thus, the story that would end in Anne’s squalid death was given an uplifting Hollywood ending.

The notion of Anne Frank’s diary as a source of redemption, or at least consolation, received a further boost from the American stage play, written by two Hollywood screenwriters, Frances Goodrich and Albert Hackett, in 1955. The famous last words in the play are taken from a diary entry on July 15, 1944: “In spite of everything, I still believe that people are really good at heart”. Thus, the story that would end in Anne’s squalid death was given an uplifting Hollywood ending. We called it El Lago. The Lake. As kids, growing up in the Guatemala of the 1970s, we probably never even knew its name—Lake Amatitlán. Nor did we care. It was only a winding, half-hour drive from the city to my grandparent’s vacation chalet on its shore. We spent most weekends and holidays of my childhood there, jumping off the wooden dock, learning to swim in the icy blue water, digging out old Mayan pots and relics from the muddy bottom, paddling out on long surfboards while little black fish jumped up through the surface and sometimes even landed on the acrylic board. Gently, we’d nudge them back in.

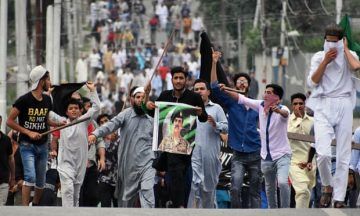

We called it El Lago. The Lake. As kids, growing up in the Guatemala of the 1970s, we probably never even knew its name—Lake Amatitlán. Nor did we care. It was only a winding, half-hour drive from the city to my grandparent’s vacation chalet on its shore. We spent most weekends and holidays of my childhood there, jumping off the wooden dock, learning to swim in the icy blue water, digging out old Mayan pots and relics from the muddy bottom, paddling out on long surfboards while little black fish jumped up through the surface and sometimes even landed on the acrylic board. Gently, we’d nudge them back in. Seventy years after partition, the annexation of Kashmir by India is the endgame of Devraj, the Hindu nationalist businessman protagonist of my 2017 novel

Seventy years after partition, the annexation of Kashmir by India is the endgame of Devraj, the Hindu nationalist businessman protagonist of my 2017 novel Helen Clapp, a professor of theoretical physics at MIT, recounted the biggest news of 21st century physics, the detection of gravitational waves by the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO), an international collaboration of scientists, resulting from the collision of two black holes more than a billion years ago. Einstein posited the existence of gravitational waves in 1915, Clapp said. “People describe these waves as ‘ripples in spacetime,’ with analogies about bowling balls on trampolines and people rolling around on mattresses, and these are probably as good as we’re going to get. The problem with all of the analogies, though, is that they’re three-dimensional; it’s almost impossible for human beings to add a fourth dimension, and visualize how objects with enormous gravity—black holes or dead stars—might bend not only space, but time.”

Helen Clapp, a professor of theoretical physics at MIT, recounted the biggest news of 21st century physics, the detection of gravitational waves by the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO), an international collaboration of scientists, resulting from the collision of two black holes more than a billion years ago. Einstein posited the existence of gravitational waves in 1915, Clapp said. “People describe these waves as ‘ripples in spacetime,’ with analogies about bowling balls on trampolines and people rolling around on mattresses, and these are probably as good as we’re going to get. The problem with all of the analogies, though, is that they’re three-dimensional; it’s almost impossible for human beings to add a fourth dimension, and visualize how objects with enormous gravity—black holes or dead stars—might bend not only space, but time.” Amitava Kumar’s recent novel, Immigrant, Montana, tells the story of Kailash, an Indian graduate student who has immigrated to the US to study at Columbia University, and his education in love as well as in academe. The novel was a New York Times Notable Book of 2018, and it has been compared to the autofiction of Teju Cole and Ben Lerner. In this interview, Kumar talks about how the novel is and is not autobiographical.

Amitava Kumar’s recent novel, Immigrant, Montana, tells the story of Kailash, an Indian graduate student who has immigrated to the US to study at Columbia University, and his education in love as well as in academe. The novel was a New York Times Notable Book of 2018, and it has been compared to the autofiction of Teju Cole and Ben Lerner. In this interview, Kumar talks about how the novel is and is not autobiographical. In 1969, W.H. Auden wrote a skeptical poem about the moon landing after he had declined a request to write a celebratory one.

In 1969, W.H. Auden wrote a skeptical poem about the moon landing after he had declined a request to write a celebratory one. I had just turned twenty-nine and he was forty-eight when we first met out there on City Island, but I quickly realized that he would make a wonderful subject for one of those multi-part profiles the magazine was famous for in those days, and across the next four years, I took on the role of a sort of beanpole Sancho to his capacious Quixote, traipsing about with him on his various rounds and travels, chronicling his in those days floridly neurotic ramblings, indeed, filling up over fifteen notebooks full of them, interviewing his friends and patients and earlier associates, and off to the side, trying to help him through that epic blockage, which, curiously, took the form of graphomania: he’d generated millions of words, just not the right ones, and, for his editors and me, most of the at times Sisyphean work consisted in pruning the damn thing back and then preventing him from mischiefing it yet further.

I had just turned twenty-nine and he was forty-eight when we first met out there on City Island, but I quickly realized that he would make a wonderful subject for one of those multi-part profiles the magazine was famous for in those days, and across the next four years, I took on the role of a sort of beanpole Sancho to his capacious Quixote, traipsing about with him on his various rounds and travels, chronicling his in those days floridly neurotic ramblings, indeed, filling up over fifteen notebooks full of them, interviewing his friends and patients and earlier associates, and off to the side, trying to help him through that epic blockage, which, curiously, took the form of graphomania: he’d generated millions of words, just not the right ones, and, for his editors and me, most of the at times Sisyphean work consisted in pruning the damn thing back and then preventing him from mischiefing it yet further. In the years before Transition House existed, violence at home was considered a private matter between husband and wife. In the early sixties, Janet, an undergraduate at a Seven Sisters college, had just married Jonathan, who was in law school. (Both names are pseudonyms.) Jonathan had started beating her up almost daily; each time, he was filled with remorse, but he blamed Janet for provoking him. Janet had not known any violence growing up, so she found the situation disturbing and bizarre and kept it a secret from most people she knew. She explained her black eyes with the usual stories about bumping into things.

In the years before Transition House existed, violence at home was considered a private matter between husband and wife. In the early sixties, Janet, an undergraduate at a Seven Sisters college, had just married Jonathan, who was in law school. (Both names are pseudonyms.) Jonathan had started beating her up almost daily; each time, he was filled with remorse, but he blamed Janet for provoking him. Janet had not known any violence growing up, so she found the situation disturbing and bizarre and kept it a secret from most people she knew. She explained her black eyes with the usual stories about bumping into things. We have been friends, Ági and I, since 1969. I was much younger than she, having been born in the last year of the War in 1944. For a moment perhaps, we might have been, my mother and I, and Ági, in one of the same houses of the international ghetto, under Swedish, Swiss or Vatican weak protection. She was 14 or 15 back then, and her dramatic survival — by jumping into the Danube in front of an Arrow Cross Firing squad — has been often recounted.

We have been friends, Ági and I, since 1969. I was much younger than she, having been born in the last year of the War in 1944. For a moment perhaps, we might have been, my mother and I, and Ági, in one of the same houses of the international ghetto, under Swedish, Swiss or Vatican weak protection. She was 14 or 15 back then, and her dramatic survival — by jumping into the Danube in front of an Arrow Cross Firing squad — has been often recounted.  The bloodbath of partition also left the two nations that were borne out of it –

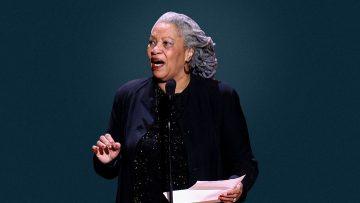

The bloodbath of partition also left the two nations that were borne out of it –  I think a lot about Toni Morrison’s 1993 Nobel Prize lecture. Morrison, who died last week at the age of 88, was one of the nation’s most revered novelists and thinkers, and has left behind an immense opus that has generated renewed interest. Her acceptance

I think a lot about Toni Morrison’s 1993 Nobel Prize lecture. Morrison, who died last week at the age of 88, was one of the nation’s most revered novelists and thinkers, and has left behind an immense opus that has generated renewed interest. Her acceptance  For the first time, researchers have teleported a qutrit, a tripartite unit of quantum information. The independent results from two teams are an important advance for the field of quantum teleportation, which has long been limited to qubits—units of quantum information akin to the binary “bits” used in classical computing. These proof-of-concept experiments demonstrate that qutrits, which can carry more information and have greater resistance to noise than qubits, may be used in future quantum networks. Chinese physicist Guang-Can Guo and his colleagues at the University of Science and Technology of China (USTC)

For the first time, researchers have teleported a qutrit, a tripartite unit of quantum information. The independent results from two teams are an important advance for the field of quantum teleportation, which has long been limited to qubits—units of quantum information akin to the binary “bits” used in classical computing. These proof-of-concept experiments demonstrate that qutrits, which can carry more information and have greater resistance to noise than qubits, may be used in future quantum networks. Chinese physicist Guang-Can Guo and his colleagues at the University of Science and Technology of China (USTC)