Sean Carroll in Preposterous Universe:

Memory takes different forms. Memories can be encoded in the strength of neural connections in our brains, but there’s a sense in which photographs and written records are memories as well. What did people do before such forms of memory even existed? Lynne Kelly is a science writer and researcher who specializes in forms of memory in the ancient world, as well as a competitive memory expert in her own right. She has theorized that ancient structures such as Stonehenge might have served as memory palaces, encoding social knowledge over extended periods of time. We talk about how to improve your own memory, the origin of religion, and how prehistoric cultures preserved their know-how.

Memory takes different forms. Memories can be encoded in the strength of neural connections in our brains, but there’s a sense in which photographs and written records are memories as well. What did people do before such forms of memory even existed? Lynne Kelly is a science writer and researcher who specializes in forms of memory in the ancient world, as well as a competitive memory expert in her own right. She has theorized that ancient structures such as Stonehenge might have served as memory palaces, encoding social knowledge over extended periods of time. We talk about how to improve your own memory, the origin of religion, and how prehistoric cultures preserved their know-how.

More here.

The climate crisis is an issue that requires long-term thinking across the generations, yet electoral politics is geared toward responding to immediate grievances. Politicians can talk about taking the long view, but without institutional changes to the way we practice democracy, they are unlikely to look beyond short-term political gains.

The climate crisis is an issue that requires long-term thinking across the generations, yet electoral politics is geared toward responding to immediate grievances. Politicians can talk about taking the long view, but without institutional changes to the way we practice democracy, they are unlikely to look beyond short-term political gains. Few political poems strike emotional pay dirt with such consistency and effect as ‘September 1, 1939’. In the sprung rhythm of his three-beat line, with each of his eleven-line stanzas containing one sentence, the language leaps at our hearts and minds. Auden’s infamous cleverness and his wide allusiveness continue after many readings to startle in satisfying ways, even when we don’t recall exactly ‘what occurred at Linz’ or really know ‘What huge imago made/A psychopathic god’. What follows, of course, from these puzzling lines is the poem’s most clarifying moment: ‘I and the public know/What all schoolchildren learn,/Those to

Few political poems strike emotional pay dirt with such consistency and effect as ‘September 1, 1939’. In the sprung rhythm of his three-beat line, with each of his eleven-line stanzas containing one sentence, the language leaps at our hearts and minds. Auden’s infamous cleverness and his wide allusiveness continue after many readings to startle in satisfying ways, even when we don’t recall exactly ‘what occurred at Linz’ or really know ‘What huge imago made/A psychopathic god’. What follows, of course, from these puzzling lines is the poem’s most clarifying moment: ‘I and the public know/What all schoolchildren learn,/Those to  Around October 20, 1969, Sanders received a copy of an ecology newsletter called Earth Read-Out in the mail. The newsletter reprinted a five-day-old San Francisco Chronicle story describing two police raids on a remote desert ranch in California: “A band of nude and long-haired thieves who ranged over Death Valley in stolen dune buggies” had been rounded up. Sanders read the story with some interest, then put it aside. Six weeks later, when Manson’s picture was plastered across the front pages of newspapers, along with reports of the horrific crimes he’d allegedly orchestrated, Sanders recalled the thieves in the desert.

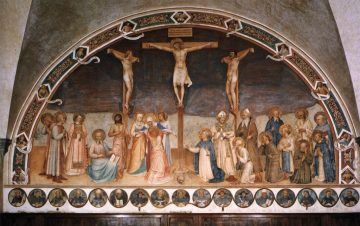

Around October 20, 1969, Sanders received a copy of an ecology newsletter called Earth Read-Out in the mail. The newsletter reprinted a five-day-old San Francisco Chronicle story describing two police raids on a remote desert ranch in California: “A band of nude and long-haired thieves who ranged over Death Valley in stolen dune buggies” had been rounded up. Sanders read the story with some interest, then put it aside. Six weeks later, when Manson’s picture was plastered across the front pages of newspapers, along with reports of the horrific crimes he’d allegedly orchestrated, Sanders recalled the thieves in the desert. In the summer of 1873, Henry James visited a former monastery on Piazza San Marco in Florence. Surrounded by a scattering of low-slung, washed-out government buildings and conical Tuscan cypresses, the church and convent were in what is still the city’s center. When James first entered the convent, he saw Fra Angelico’s The Crucifixion with Saints in the chapter room. A brightly colored, semicircle fresco about thirty feet wide, Crucifixion depicts Christ and the two thieves on either side of him, nailed to their crosses, as saints and witnesses grieve below. “I looked long,” James wrote. “One can hardly do otherwise.” As the author moved throughout what had then just become a museum, he felt a spiritual urge, even though he had rejected his Christian upbringing. “You may be as little of a formal Christian as Fra Angelico was much of one,” he wrote in Italian Hours. “You yet feel admonished by spiritual decency to let so yearning a view of the Christian story work its utmost will on you.” Even Angelico’s colors, he added, seem divinely infinite, “dissolved in tears that drop and drop, however softly, through all time.”

In the summer of 1873, Henry James visited a former monastery on Piazza San Marco in Florence. Surrounded by a scattering of low-slung, washed-out government buildings and conical Tuscan cypresses, the church and convent were in what is still the city’s center. When James first entered the convent, he saw Fra Angelico’s The Crucifixion with Saints in the chapter room. A brightly colored, semicircle fresco about thirty feet wide, Crucifixion depicts Christ and the two thieves on either side of him, nailed to their crosses, as saints and witnesses grieve below. “I looked long,” James wrote. “One can hardly do otherwise.” As the author moved throughout what had then just become a museum, he felt a spiritual urge, even though he had rejected his Christian upbringing. “You may be as little of a formal Christian as Fra Angelico was much of one,” he wrote in Italian Hours. “You yet feel admonished by spiritual decency to let so yearning a view of the Christian story work its utmost will on you.” Even Angelico’s colors, he added, seem divinely infinite, “dissolved in tears that drop and drop, however softly, through all time.” Jay Shetty is 8 years old. He is smart and bright, says his mother Shilpa, even if he can’t do all the things his younger brother can. “Jay doesn’t sit up or use his hands much. He’s non-verbal and we don’t know how well he can see,” she says. “But he plays with us and tries to copy everything his younger brother Kairav does.”

Jay Shetty is 8 years old. He is smart and bright, says his mother Shilpa, even if he can’t do all the things his younger brother can. “Jay doesn’t sit up or use his hands much. He’s non-verbal and we don’t know how well he can see,” she says. “But he plays with us and tries to copy everything his younger brother Kairav does.” One day, doctors may be able to use the metabolites in blood samples to predict the likelihood of a person surviving another five to 10 years, according to a newly developed tool described today (August 20) in

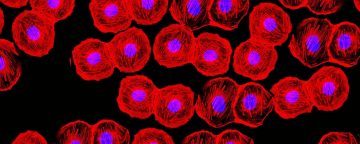

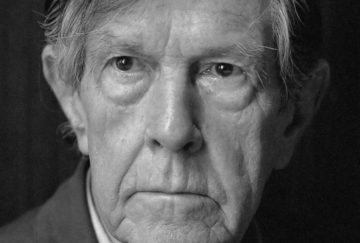

One day, doctors may be able to use the metabolites in blood samples to predict the likelihood of a person surviving another five to 10 years, according to a newly developed tool described today (August 20) in  Milton Babbitt and John Cage, two of the most notorious postwar American composers, are often thought to be antipodal figures. Babbitt is straight, Jewish, politically conservative, and southern, a skeptical rationalist who talks like a mathematician on speed. Cage–who died in 1992–was gay, goyish, politically left, and Californian, a genial fruitcake whose enthusiasms ran toward astrology, mushrooms, Zen, and anarchist politics. Babbitt’s music is fastidiously organized, each of his notes carefully placed within multiple nested rhythmic and melodic patterns. Cage’s music, by contrast, is scrupulously disorganized, composed randomly–for instance by tossing coins or tracing astronomical maps onto music paper. Not surprisingly, Babbitt is an academic, and has many students who teach at music departments throughout the country. Cage, who never graduated from college, was an auto-didact (more or less), and has had at least as much influence on visual arts and popular music as on the world of academic musical composition.

Milton Babbitt and John Cage, two of the most notorious postwar American composers, are often thought to be antipodal figures. Babbitt is straight, Jewish, politically conservative, and southern, a skeptical rationalist who talks like a mathematician on speed. Cage–who died in 1992–was gay, goyish, politically left, and Californian, a genial fruitcake whose enthusiasms ran toward astrology, mushrooms, Zen, and anarchist politics. Babbitt’s music is fastidiously organized, each of his notes carefully placed within multiple nested rhythmic and melodic patterns. Cage’s music, by contrast, is scrupulously disorganized, composed randomly–for instance by tossing coins or tracing astronomical maps onto music paper. Not surprisingly, Babbitt is an academic, and has many students who teach at music departments throughout the country. Cage, who never graduated from college, was an auto-didact (more or less), and has had at least as much influence on visual arts and popular music as on the world of academic musical composition. Aggressive cancers can spread so fiercely that they seem less like tissues gone wrong and more like invasive parasites looking to consume and then break free of their host. If a wild theory

Aggressive cancers can spread so fiercely that they seem less like tissues gone wrong and more like invasive parasites looking to consume and then break free of their host. If a wild theory  In the summer of 1987,

In the summer of 1987, Rather unintentionally, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers owns an enormous collection of fossils that would turn any paleontologist green with envy. “The U.S. Army Corps has collections that span the paleontological record,” says Nancy Brighton, a supervisory archaeologist for the Corps. “Basically anything related to animals and the natural world before humans came onto the scene.” The Corps never set out to amass this prehistoric tome. Rather, the fossils—from trilobites to dinosaurs, and everything in between—came as a kind of byproduct of the Corps’s actual, more logistical purpose: flood control (among other large-scale civil engineering projects).

Rather unintentionally, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers owns an enormous collection of fossils that would turn any paleontologist green with envy. “The U.S. Army Corps has collections that span the paleontological record,” says Nancy Brighton, a supervisory archaeologist for the Corps. “Basically anything related to animals and the natural world before humans came onto the scene.” The Corps never set out to amass this prehistoric tome. Rather, the fossils—from trilobites to dinosaurs, and everything in between—came as a kind of byproduct of the Corps’s actual, more logistical purpose: flood control (among other large-scale civil engineering projects). Lynskey’s background in musical criticism also leads to a highly original intervention in the ongoing debate over how authors influence one another. This has long been a contentious subject with respect to Orwell. Before composing 1984, Orwell claimed that Aldous Huxley’s classic satire warning of the dangers of hedonism and materialism, Brave New World (1932), essentially plagiarised Yevgeny Zamyatin’s We, a Soviet science fiction novel published in the 1920s. Critics later raised their eyebrows at how much Orwell’s own account of a conformist-mad land, which was published in 1949, owed to both of those earlier works.

Lynskey’s background in musical criticism also leads to a highly original intervention in the ongoing debate over how authors influence one another. This has long been a contentious subject with respect to Orwell. Before composing 1984, Orwell claimed that Aldous Huxley’s classic satire warning of the dangers of hedonism and materialism, Brave New World (1932), essentially plagiarised Yevgeny Zamyatin’s We, a Soviet science fiction novel published in the 1920s. Critics later raised their eyebrows at how much Orwell’s own account of a conformist-mad land, which was published in 1949, owed to both of those earlier works. Realism is back. After several decades of denying there was anything beyond interpretation, thinkers in the postmodern tradition are returning to reality. A new cluster of Continental thinkers—including Maurizio Ferraris, Graham Harman, and Markus Gabriel—argue that realism was unjustly, and unwisely, abandoned. While part of their motivation is purely philosophical, they also see realism as a defense against a crude, Nietzschean style of politics exemplified by a crop of world leaders who act as though the truth is whatever they say it is. Even in sociology, the thin, metaphysics-free theorizing of rational actor theory has been joined by “critical realism,” a metaphysically heavyweight view that accepts that things have objective natures that make them what they are, and powers that enable real causal interactions between things.

Realism is back. After several decades of denying there was anything beyond interpretation, thinkers in the postmodern tradition are returning to reality. A new cluster of Continental thinkers—including Maurizio Ferraris, Graham Harman, and Markus Gabriel—argue that realism was unjustly, and unwisely, abandoned. While part of their motivation is purely philosophical, they also see realism as a defense against a crude, Nietzschean style of politics exemplified by a crop of world leaders who act as though the truth is whatever they say it is. Even in sociology, the thin, metaphysics-free theorizing of rational actor theory has been joined by “critical realism,” a metaphysically heavyweight view that accepts that things have objective natures that make them what they are, and powers that enable real causal interactions between things. Ramallah, in the heart of the West Bank, is only a few miles north of Jerusalem, its nose pressed up against the dashes of Palestine’s borders on the maps, official markers of the city’s – and the country’s – provisional nature. It is a place of scarcely 30,000 inhabitants, historically a Christian city (although now the majority are Muslim) and also one of cold winters and carefully tended gardens, chosen by the PLO as its de facto headquarters following the Oslo accords of 1993 and 1995. It is, above all, a city of authors, home to Palestine’s greatest poet, the late

Ramallah, in the heart of the West Bank, is only a few miles north of Jerusalem, its nose pressed up against the dashes of Palestine’s borders on the maps, official markers of the city’s – and the country’s – provisional nature. It is a place of scarcely 30,000 inhabitants, historically a Christian city (although now the majority are Muslim) and also one of cold winters and carefully tended gardens, chosen by the PLO as its de facto headquarters following the Oslo accords of 1993 and 1995. It is, above all, a city of authors, home to Palestine’s greatest poet, the late  TSAKANE, South Africa — When she joined a trial of new tuberculosis drugs, the dying young woman weighed just 57 pounds. Stricken with a deadly strain of the disease, she was mortally terrified. Local nurses told her the Johannesburg hospital to which she must be transferred was very far away — and infested with vervet monkeys. “I cried the whole way in the ambulance,” Tsholofelo Msimango recalled recently. “They said I would live with monkeys and the sisters there were not nice and the food was bad and there was no way I would come back. They told my parents to fix the insurance because I would die.” Five years later, Ms. Msimango, 25, is now tuberculosis-free. She is healthy at 103 pounds, and has a young son. The trial she joined was small — it enrolled only 109 patients — but experts are calling the preliminary results groundbreaking. The drug regimen tested on Ms. Msimango has shown a 90 percent success rate against a deadly plague, extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis.

TSAKANE, South Africa — When she joined a trial of new tuberculosis drugs, the dying young woman weighed just 57 pounds. Stricken with a deadly strain of the disease, she was mortally terrified. Local nurses told her the Johannesburg hospital to which she must be transferred was very far away — and infested with vervet monkeys. “I cried the whole way in the ambulance,” Tsholofelo Msimango recalled recently. “They said I would live with monkeys and the sisters there were not nice and the food was bad and there was no way I would come back. They told my parents to fix the insurance because I would die.” Five years later, Ms. Msimango, 25, is now tuberculosis-free. She is healthy at 103 pounds, and has a young son. The trial she joined was small — it enrolled only 109 patients — but experts are calling the preliminary results groundbreaking. The drug regimen tested on Ms. Msimango has shown a 90 percent success rate against a deadly plague, extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis. I don’t know a lot about guns.

I don’t know a lot about guns.