by Marie Snyder

It feels like I understand the idea that all suffering comes from expectation in a way I didn’t used to. Now it seems so obvious, but I’m not really sure what flip was switched. It’s not just that if we stop expecting to get things, we’ll be happier, but how ridiculous it is to expect anything to stay the same at all, much less get better, ever. And that understanding seems to help reduce some anxiety over the things that can’t be easily changed. Suffering is inevitable, but it can be somewhat diminished in order to have more contentment. We can change what counts as suffering, and we can change our perspective around tragedies, so maybe we can also change how we can continue to bear witness to, or experience, absolute atrocities.

It feels like I understand the idea that all suffering comes from expectation in a way I didn’t used to. Now it seems so obvious, but I’m not really sure what flip was switched. It’s not just that if we stop expecting to get things, we’ll be happier, but how ridiculous it is to expect anything to stay the same at all, much less get better, ever. And that understanding seems to help reduce some anxiety over the things that can’t be easily changed. Suffering is inevitable, but it can be somewhat diminished in order to have more contentment. We can change what counts as suffering, and we can change our perspective around tragedies, so maybe we can also change how we can continue to bear witness to, or experience, absolute atrocities.

One simple way to reduce suffering is to narrow the definition. Comedian Michelle Wolf jokes, “It’s hard to have a struggle and a skin care routine,” which clarifies that we might be considering some difficulties as suffering in a way that doesn’t fly when we widen the scope of our horizons. Pain is pain and can’t definitively be compared, yet I believe many of us have an automatic judgment in our heads that lists events in a hierarchy. Typically suffering from having to do a task we don’t want to do, like write a boring report or clean out the fridge, or from wanting luxuries we can’t afford, like another trip, might be relegated to the bottom as whining. The pain from it is there, though: the agony and stress from uninteresting maintenance that’s necessary to further our own existence or the grief over lost opportunities. Furthermore, it can develop an extra layer of shame on top of the suffering if we try and fail to elicit sympathy for having so much food that some is left to rot and needs to be cleaned. When we realize we can’t afford that trip after all, this is a suffering we are expected to bear without complaint.

The shame on top of the very real distress doesn’t help, but a different perspective might: comparing to those worse off, recognizing the tasks as merely one choice with alternatives that are even less pleasant, or maybe even finding ways to enjoy the task or staycation are ideas passed down for millenia. If we can increase our distress tolerance around these lesser calamities, then we can potentially wipe out the bottom layer of our pile of pain. Read more »

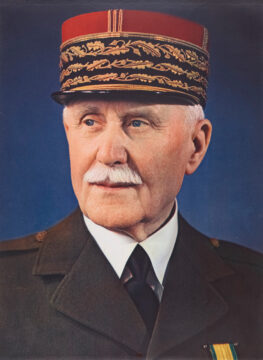

In Timur Vermes’ best-selling novel Er ist wieder da (‘He’s back’), Adolf Hitler wakes up in Berlin. Somewhat disoriented after discovering the year is 2011, he soon finds his way to the public eye again: he is understandably regarded as a skilled Hitler impersonator, an excellent ironic act for a 21st-century comedy show. His handlers don’t mind the fact that he never breaks character.

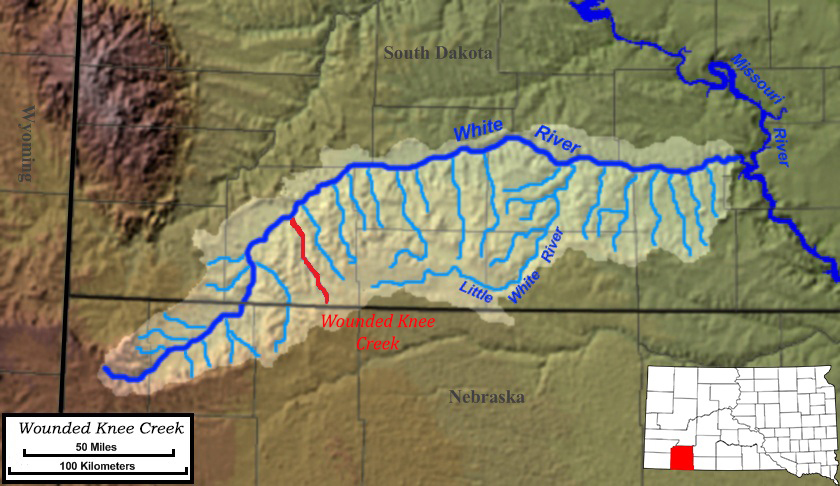

In Timur Vermes’ best-selling novel Er ist wieder da (‘He’s back’), Adolf Hitler wakes up in Berlin. Somewhat disoriented after discovering the year is 2011, he soon finds his way to the public eye again: he is understandably regarded as a skilled Hitler impersonator, an excellent ironic act for a 21st-century comedy show. His handlers don’t mind the fact that he never breaks character. The Lakota name for Wounded Knee Creek is Čaŋkpe Opi Wakpala. The first letter is a -ch sound. The ŋ signifies not an n, but nasalization as when you say unh-unh to mean no.

The Lakota name for Wounded Knee Creek is Čaŋkpe Opi Wakpala. The first letter is a -ch sound. The ŋ signifies not an n, but nasalization as when you say unh-unh to mean no.

1. Roses

1. Roses

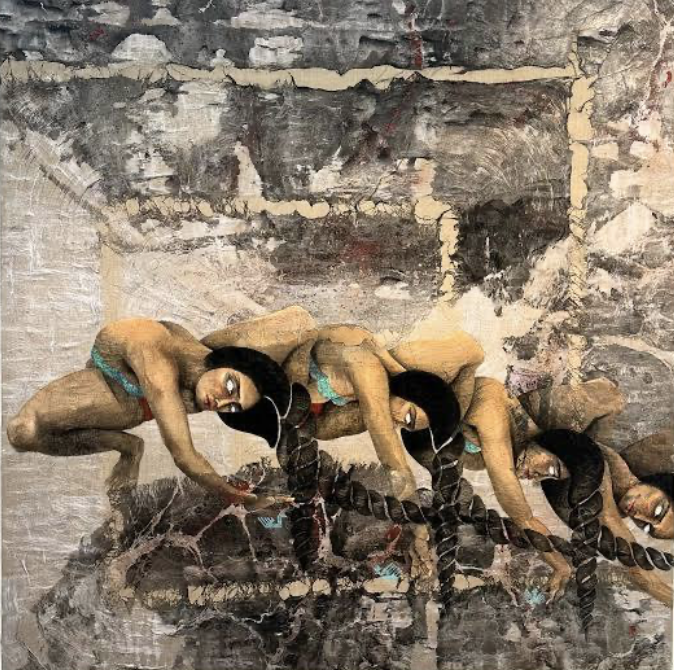

Hayv Kahraman. Rain Birds Ritual, 2025.

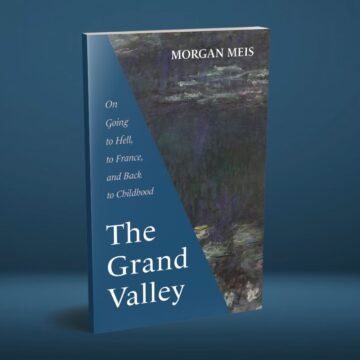

Hayv Kahraman. Rain Birds Ritual, 2025. Morgan Meis and I have been talking about art for years. We’re friends and interlocutors, so I’ll refer to him by first name here for the sake of transparency. Morgan writes about painting; I write about movies. We spent the pandemic exchanging letters with each other about films by Terrence Malick, Lars von Trier, and Krzysztof Kieślowski. These letters were later collected in a mad book called

Morgan Meis and I have been talking about art for years. We’re friends and interlocutors, so I’ll refer to him by first name here for the sake of transparency. Morgan writes about painting; I write about movies. We spent the pandemic exchanging letters with each other about films by Terrence Malick, Lars von Trier, and Krzysztof Kieślowski. These letters were later collected in a mad book called

The other day, in a cavernous sports superstore, I thought of J.G. Ballard. Echoey. Compartmentalised. Fluorescent. Stuffed with product. It was, probably quite obviously, the sort of place Ballard might have imagined the norms of society suddenly collapsing in on themselves, unable to carry their own contradictions.

The other day, in a cavernous sports superstore, I thought of J.G. Ballard. Echoey. Compartmentalised. Fluorescent. Stuffed with product. It was, probably quite obviously, the sort of place Ballard might have imagined the norms of society suddenly collapsing in on themselves, unable to carry their own contradictions.