by Ethan Seavey

On the night that I first told someone else that I was gay, the world was held together with a single phrase which was echoed from speaker to listener and back again. My friend and I were both queer but I was the first one saying it. So for us, it was healing to say and to hear: “It doesn’t mean anything. I (or you) won’t let it define me (or you).” We repeated this wish, that someone’s sexuality could be considered separate from their social identity. I decided to trust that I could be gay, but not this or that kind of gay, just myself. I used the phrase like a prayer and begged that I could exist in a straight-minded Catholic world. It worked for a few months. Then I started to tell more people. Two more friends and then my parents. Siblings and more friends. And finally, everyone. Most everyone was kind and most everyone said it didn’t change a thing. But it changed many things. I finally accepted that I was the Queer.

The Queer is a lonely identity. They are raised believing that they are and can be the same as everyone else, but as they grow up, they realize that they are The Queer in a space that is not made for them. They are The Only Queer in a class of three hundred, but they heard there’s another Queer in the grade above. They don’t speak to one another because they are afraid to be seen associating. They realize that they will never have the lives of their parents.

The Queer must reckon with the close-minded Gods that dominate the globe. They are born into a world that is not made for them and given an identity that defines them forever. This world is ruled by a strong God in the clouds who supports the structure that hurts them. With tall walls He puts each person in a room and investigates them. He studies the outliers; not to know them, but to find out ways to make them fit in. Read more »

One of the most interesting debates within the larger discussion around large language models (LLMs) such as GPT-4 is whether they are just mindless generators of plausible text derived from their training – sometimes termed “

One of the most interesting debates within the larger discussion around large language models (LLMs) such as GPT-4 is whether they are just mindless generators of plausible text derived from their training – sometimes termed “

Misha Japanwala. Breastplate, ca. 2018.

Misha Japanwala. Breastplate, ca. 2018.

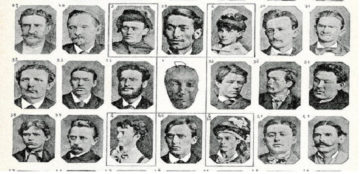

When they arrived in the U.S., Southern Italians brought with them the sense that they’d been branded as underdogs, that they belonged and would forever belong to a lower class, but the birth of the Italian-American gangster was rooted in attitudes toward the Mezzogiorno that dated back far earlier. After Italy was unified under Vittorio Emanuele II in 1861, a new national government imposed Piedmont’s centralized administrative system on the South, which led to violent rebellion against State authority. Politicians and intellectuals took pains to deflect responsibility for what they saw as the “barbarism” of the Mezzogiorno, and were particularly receptive to theories that placed the blame for the South’s many problems on Southern Italians’ own inborn brutishness. The decades following Unification saw the nascent fields of criminal anthropology and psychiatry establish themselves in the universities of Northern Italy; implementing the pseudosciences of phrenology and anthropometry in their search for evolutionary remnants of an arrested stage of human development manifested in the people of the Mezzogiorno, they used various instruments to measure human skulls, ears, foreheads, jaws, arms, and other body parts, catalogued these, and correlated them with undesirable behavioral characteristics, inventing in the process a Southern Italian race entirely separate from and unrelated to a superior Northern race and officially confirming the biological origins of Southern “savagery.”

When they arrived in the U.S., Southern Italians brought with them the sense that they’d been branded as underdogs, that they belonged and would forever belong to a lower class, but the birth of the Italian-American gangster was rooted in attitudes toward the Mezzogiorno that dated back far earlier. After Italy was unified under Vittorio Emanuele II in 1861, a new national government imposed Piedmont’s centralized administrative system on the South, which led to violent rebellion against State authority. Politicians and intellectuals took pains to deflect responsibility for what they saw as the “barbarism” of the Mezzogiorno, and were particularly receptive to theories that placed the blame for the South’s many problems on Southern Italians’ own inborn brutishness. The decades following Unification saw the nascent fields of criminal anthropology and psychiatry establish themselves in the universities of Northern Italy; implementing the pseudosciences of phrenology and anthropometry in their search for evolutionary remnants of an arrested stage of human development manifested in the people of the Mezzogiorno, they used various instruments to measure human skulls, ears, foreheads, jaws, arms, and other body parts, catalogued these, and correlated them with undesirable behavioral characteristics, inventing in the process a Southern Italian race entirely separate from and unrelated to a superior Northern race and officially confirming the biological origins of Southern “savagery.”

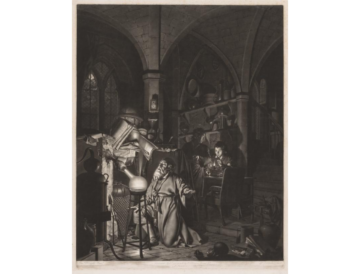

Moeen Faruqi. Chamber Dialogue, 2016.

Moeen Faruqi. Chamber Dialogue, 2016.