by Lydia Stryk

Riding the train to the small city of Darmstadt to sleep over with a friend after a day spent at the Frankfurt Book Fair, I observed an impeccably dressed elderly gentleman sitting several rows away from me across the aisle.

He wore an elegant calf-length overcoat which men of a certain class in Germany are partial to wearing. His shoes were fine leather and shining. He was tall, with excellent posture, a full mane of white hair and the bluest of eyes, which I noted because they reminded me of my father’s eyes and because they were staring into the beyond behind me. He was in possession of a large expensive-looking wrist watch to which he turned his attention occasionally. And though I could see no evidence of a briefcase, his would have been top of the line.

He had, in fact, the air of a publisher of tasteful literary titles on his way home from a successful but tiring day at the fair. And I pictured him the sort who would have attended the fair every year without exception until the pandemic temporarily shut it down and would continue to attend, out of habit, for as long as he was able. Perhaps, he was the scion of a publishing empire, I told myself, a fitting story.

It had been a long day, and I was happy to be on the train. Nothing else about the day had been happy, so eventually my mind wandered away from the old man to my own state of affairs. I was cold and hungry and admittedly forlorn, none of this conducive to conjecture and true curiosity. I closed my eyes.

And that is when a certain commotion broke out on the until-that-moment quiet and peaceable train. Concerned women’s voices could be heard, and I opened my eyes to find the concern centered around the elegant elderly man. My station was approaching and though readying to disembark, I was able to make out the following: The elderly gentleman had apparently turned to his seat companion and asked her where the train was heading and if she could tell him where he was. Upon questioning, it became clear that he did not know where he wanted to go. The literary lion of my imagination had presumably boarded a train with no direction or purpose and was lost. Read more »

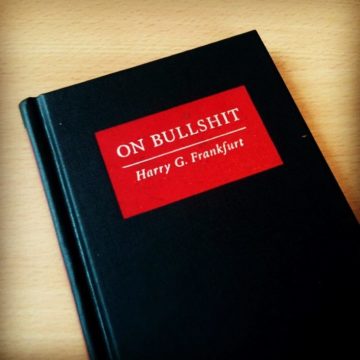

Harry Frankfurt, who died of congestive heart failure this July, was a rare academic philosopher whose work managed to shape popular discourse. During the Trump years, his explication of bullshit became a much used lens through which to view Trump’s post-truth political rhetoric, eventually becoming deeply associated with liberal politics.

Harry Frankfurt, who died of congestive heart failure this July, was a rare academic philosopher whose work managed to shape popular discourse. During the Trump years, his explication of bullshit became a much used lens through which to view Trump’s post-truth political rhetoric, eventually becoming deeply associated with liberal politics. Aesthetic properties in art works are peculiar. They appear to be based on objective features of an object. Yet, we typically use the way a work of art makes us feel to identify the aesthetic properties that characterize it. However, dispassionate observer cases show that even when the feelings are absent, the aesthetic properties can still be recognized as such. Feelings seem both necessary yet unnecessary for appreciation of the work.

Aesthetic properties in art works are peculiar. They appear to be based on objective features of an object. Yet, we typically use the way a work of art makes us feel to identify the aesthetic properties that characterize it. However, dispassionate observer cases show that even when the feelings are absent, the aesthetic properties can still be recognized as such. Feelings seem both necessary yet unnecessary for appreciation of the work. ed to be protected from blasphemy, I must have overheard someone say

ed to be protected from blasphemy, I must have overheard someone say  The other day, over cigarettes and beer, my friend M. told me the story of the Ghost Cop of Rowan Oak. She was speaking from authority, as she had just encountered it a few days before. Her boyfriend P. was there—both at Rowan Oak and on my front porch with the cigarettes and the beer—and it was nice to watch them swing on the swing and finish each other’s sentences.

The other day, over cigarettes and beer, my friend M. told me the story of the Ghost Cop of Rowan Oak. She was speaking from authority, as she had just encountered it a few days before. Her boyfriend P. was there—both at Rowan Oak and on my front porch with the cigarettes and the beer—and it was nice to watch them swing on the swing and finish each other’s sentences.

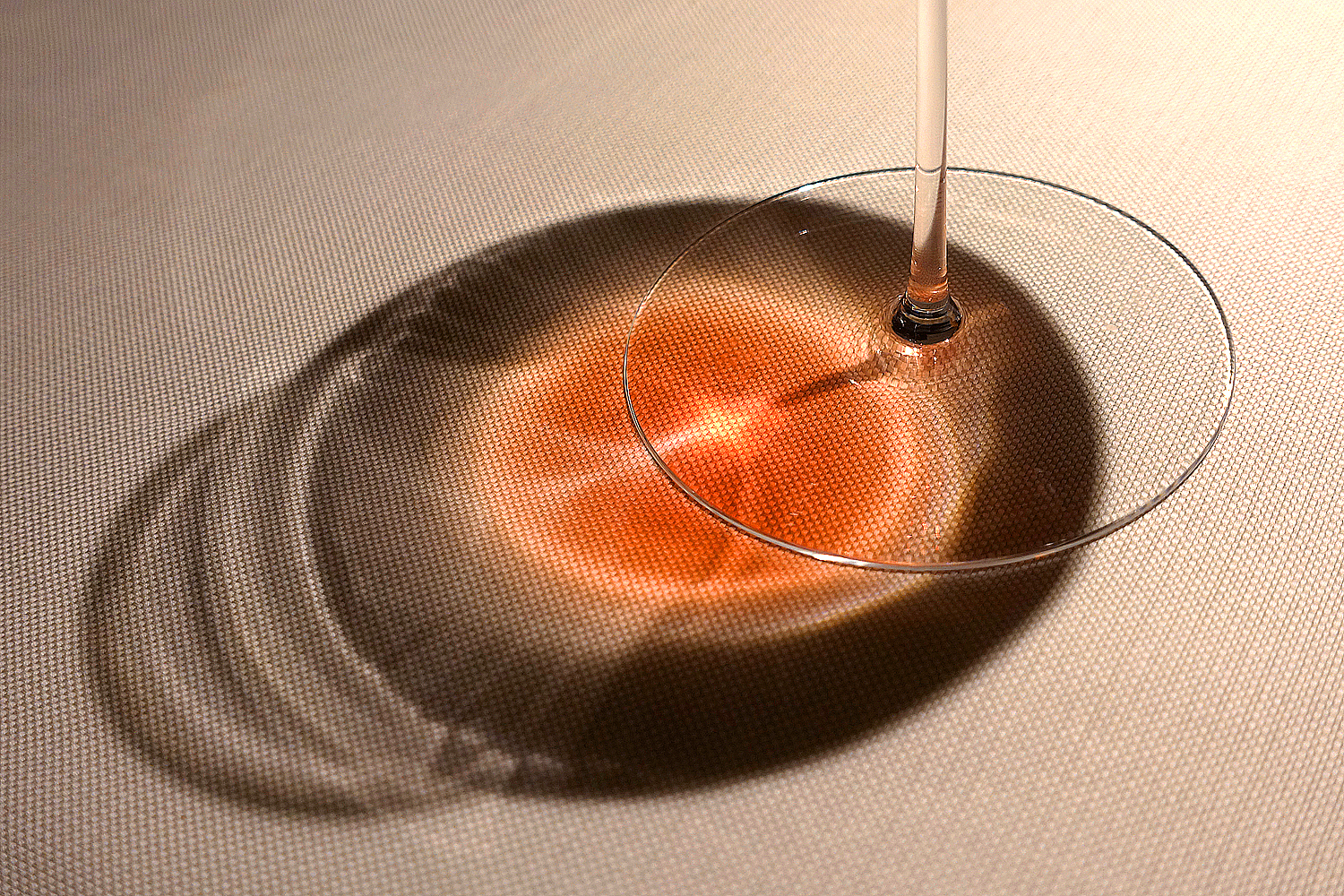

Today marks eight years since I had my last drink. Or maybe yesterday marks that anniversary; I’m not sure. It was that kind of last drink. The kind of last drink that ends with the memory of concrete coming up to meet your head like a pillow, of red and blue lights reflected off the early morning pavement on the bridge near your house, the only sound cricket buzz in the dewy August hours before dawn. The kind of last drink that isn’t necessarily so different from the drink before it, but made only truly exemplary by the fact that there was never a drink after it (at least so far, God willing). My sobriety – as a choice, an identity, a life-raft – is something that those closest to me are aware of, and certainly any reader of my essays will note references to having quit drinking, especially if they’re similarly afflicted and are able to discern the liquor-soaked bread-crumbs that I sprinkle throughout my prose. But I’ve consciously avoided personalizing sobriety too much, out of fear of being a recovery writer, or of having to speak on behalf of a shockingly misunderstood group of people (there is cowardice in that position). Mostly, however, my relative silence is because we tribe of reformed dipsomaniacs are a superstitious lot, and if anything, that’s what keeps me from emphatically declaring my sobriety as such.

Today marks eight years since I had my last drink. Or maybe yesterday marks that anniversary; I’m not sure. It was that kind of last drink. The kind of last drink that ends with the memory of concrete coming up to meet your head like a pillow, of red and blue lights reflected off the early morning pavement on the bridge near your house, the only sound cricket buzz in the dewy August hours before dawn. The kind of last drink that isn’t necessarily so different from the drink before it, but made only truly exemplary by the fact that there was never a drink after it (at least so far, God willing). My sobriety – as a choice, an identity, a life-raft – is something that those closest to me are aware of, and certainly any reader of my essays will note references to having quit drinking, especially if they’re similarly afflicted and are able to discern the liquor-soaked bread-crumbs that I sprinkle throughout my prose. But I’ve consciously avoided personalizing sobriety too much, out of fear of being a recovery writer, or of having to speak on behalf of a shockingly misunderstood group of people (there is cowardice in that position). Mostly, however, my relative silence is because we tribe of reformed dipsomaniacs are a superstitious lot, and if anything, that’s what keeps me from emphatically declaring my sobriety as such.