by Mary Hrovat

The other day, one of my grandsons asked me if I’d like to play Mario Kart with him. It goes against my grain to turn down invitations from my grandsons. However, when we’d played Mario Kart a few weeks earlier, I’d been terrible at it. His younger brother, watching from the sidelines, wanted to know why I played so badly. I said it was because the game was new to me, but in fact I’ve always been slow and clumsy at games that require quick reactions and hand-eye coordination, back to Pac-Man and even earlier. As an undergrad I was good at an arcade version of Trivial Pursuit, but that cuts no ice with anyone these days.

The other day, one of my grandsons asked me if I’d like to play Mario Kart with him. It goes against my grain to turn down invitations from my grandsons. However, when we’d played Mario Kart a few weeks earlier, I’d been terrible at it. His younger brother, watching from the sidelines, wanted to know why I played so badly. I said it was because the game was new to me, but in fact I’ve always been slow and clumsy at games that require quick reactions and hand-eye coordination, back to Pac-Man and even earlier. As an undergrad I was good at an arcade version of Trivial Pursuit, but that cuts no ice with anyone these days.

So I asked if we could play another game instead. My grandson wasn’t interested in any of the games I suggested; I suspect he was still hoping for a video game. Then one of his parents proposed that we play euchre. My daughter-in-law started setting up the card table; my son went for a deck of cards. My grandson and I teamed up to play the two of them. My younger grandson, who had shown me his rock museum and drawings from a nature journal earlier, washed his hands of card games and went to play outside.

∞

My son walked us through a sample round. Card games often mystify me, and some twenty-five years earlier my sons had tried to teach me euchre, without success. I’d thought that absolutely nothing about the game had stuck with me, beyond the fact that you use only some of the cards (the 9 to the ace of each suit). However, it looked more familiar than I expected. And somewhere between my late 30s and my early 60s, I’d become more relaxed about arbitrary rules (in part because I’d learned a lot about ignoring the unimportant ones). I could accept with equanimity the statement that the jack of spades can, in some situations, be considered a club. I understood the use of the words leading and following. I started to get the point. Read more »

In geometry, a line goes on and on: it goes on and on and never stops. In poetry, a line goes on as long as the poet lets it….though in practice this rarely means more than six or seven words at a stretch.

In geometry, a line goes on and on: it goes on and on and never stops. In poetry, a line goes on as long as the poet lets it….though in practice this rarely means more than six or seven words at a stretch.

There has been talk in recent years of what is termed “the internet novel.” The internet, or more precisely, the smartphone, poses a problem for novels. If a contemporary novel wants to seem realistic, or true to life, it must incorporate the internet in some way, because most people spend their days immersed in it. Characters, for example, must check their phones frequently. For example:

There has been talk in recent years of what is termed “the internet novel.” The internet, or more precisely, the smartphone, poses a problem for novels. If a contemporary novel wants to seem realistic, or true to life, it must incorporate the internet in some way, because most people spend their days immersed in it. Characters, for example, must check their phones frequently. For example:

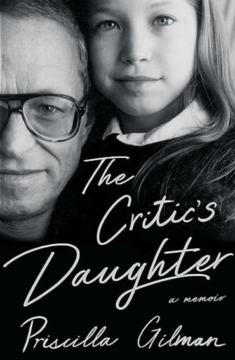

Richard Gilman (1923-2006)—a revered and feared American critic of theater, film and fiction in the mid-century patrician grain of Eric Bentley, Stanley Kauffmann and Robert Brustein—was a self-absorbed titan of insecurity and the best writing teacher I ever had. Negotiating the minefield of this man’s mercurial moodiness, beginning at age 22, was one of the main galvanizing experiences of my pre-professional life.

Richard Gilman (1923-2006)—a revered and feared American critic of theater, film and fiction in the mid-century patrician grain of Eric Bentley, Stanley Kauffmann and Robert Brustein—was a self-absorbed titan of insecurity and the best writing teacher I ever had. Negotiating the minefield of this man’s mercurial moodiness, beginning at age 22, was one of the main galvanizing experiences of my pre-professional life.