by Dwight Furrow

In an age where there is little agreement about anything, there is one assertion almost everyone agrees with—there is no disputing taste. If someone likes simple food instead of complex concoctions, who is to say that’s wrong. If I prefer bodice rippers to 19th Century Russian novels, you might say my tastes are crude and uncultured but hesitate to say one type of literary work is inherently better than the other. Aesthetic judgments are about subjective preference only. This is especially true of food and drink. Our preferences in this domain seem especially subjective. You can’t be wrong if you dislike chocolate ice cream can you?

In an age where there is little agreement about anything, there is one assertion almost everyone agrees with—there is no disputing taste. If someone likes simple food instead of complex concoctions, who is to say that’s wrong. If I prefer bodice rippers to 19th Century Russian novels, you might say my tastes are crude and uncultured but hesitate to say one type of literary work is inherently better than the other. Aesthetic judgments are about subjective preference only. This is especially true of food and drink. Our preferences in this domain seem especially subjective. You can’t be wrong if you dislike chocolate ice cream can you?

But this view that aesthetic judgment can only be about subjective preferences misses a common experience that I imagine we all have from time to time. We experience something we acknowledge to be good, but we just don’t like it. For me, the aforementioned Russian novelists provide good examples; and don’t even mention James Joyce. Each of the several times I have tried to make it through Ulysses, I was persuaded of Joyce’s greatness in the first 20 pages while being thoroughly convinced that life is too short.

This coming apart of what we enjoy from what we deem “good” suggests that some aesthetic objects are more valuable than others. But on what grounds can we make such judgments? Today it seems as if we are more suspicious of appeals to values than we used to be. Over the past several decades, we’ve come to suspect that value judgements are too often based on illegitimate hierarchies and exclude people who don’t have the “right sort” of experience or training. No doubt, some value judgements are disguised assertions of cultural dominance. But in condemning value talk we don’t escape their grip on us. The accusation that someone is too judgmental has its own normative force. There is performative contradiction in judging someone for being too judgmental.

We can’t dispense with value judgments because we can’t avoid decisions about what is better or worse. Read more »

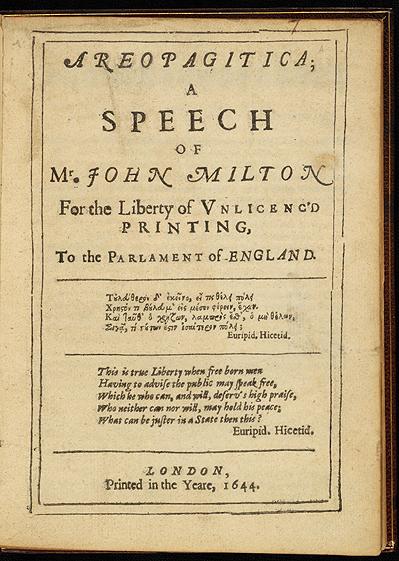

How do we regulate a revolutionary new technology with great potential for harm and good? A 380-year-old polemic provides guidance.

How do we regulate a revolutionary new technology with great potential for harm and good? A 380-year-old polemic provides guidance. Firelei Báez. Sans-Souci, (This threshold between a dematerialized and a historicized body), 2015.

Firelei Báez. Sans-Souci, (This threshold between a dematerialized and a historicized body), 2015.

I take the row covers off of two forty-foot rows of beans (three varieties) as the plants have become so big so fast in the ungodly heat they are pressing against the cloth. Afterwards, in the early evening, I let the chickens out of their sweltering little house to run free for a couple of hours. I will watch them to see if they bother the plants. The birds might peck at and scratch up the bean plants, but these plants are so large the birds should be indifferent to them. The experiment is a success: The plants bask in full sunlight while the birds rummage for grubs around them. I decide to leave the row covers off for now and will recover them at night to deter the deer. One’s smallness is manifested in gardening, as the gardener is a single organism set against myriads. It is wise to tend to one’s insignificance during these times. Come what may, no one will care much about those who stay at home husbanding rows of Maxibel haricots.

I take the row covers off of two forty-foot rows of beans (three varieties) as the plants have become so big so fast in the ungodly heat they are pressing against the cloth. Afterwards, in the early evening, I let the chickens out of their sweltering little house to run free for a couple of hours. I will watch them to see if they bother the plants. The birds might peck at and scratch up the bean plants, but these plants are so large the birds should be indifferent to them. The experiment is a success: The plants bask in full sunlight while the birds rummage for grubs around them. I decide to leave the row covers off for now and will recover them at night to deter the deer. One’s smallness is manifested in gardening, as the gardener is a single organism set against myriads. It is wise to tend to one’s insignificance during these times. Come what may, no one will care much about those who stay at home husbanding rows of Maxibel haricots.

This week marks one year since Affirmative Action was repealed by the Supreme Court. The landmark ruling was a watershed moment in how we think of race and social mobility in the United States. But for high schoolers, the crux of the case lies somewhere else entirely.

This week marks one year since Affirmative Action was repealed by the Supreme Court. The landmark ruling was a watershed moment in how we think of race and social mobility in the United States. But for high schoolers, the crux of the case lies somewhere else entirely.

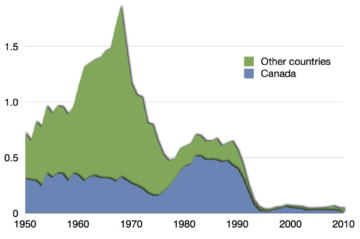

Arguably the greatest global health policy failure has been the US Department of Health and Human Services’ (HHS) refusal to promulgate any regulations to first mitigate and then eliminate the healthcare industry’s significant carbon footprint.

Arguably the greatest global health policy failure has been the US Department of Health and Human Services’ (HHS) refusal to promulgate any regulations to first mitigate and then eliminate the healthcare industry’s significant carbon footprint.

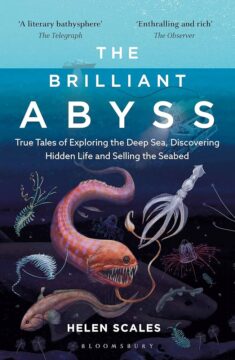

Marine biologist Helen Scales’ previous book The Brilliant Abyss: True Tales of Exploring the Deep Sea, Discovering Hidden Life and Selling the Seabed, brilliantly provided us with a glimpse of the wondrous life forms that inhabit the abyss, the deep sea. She also made known her profound concern for the future of ocean life posed by human activity. She now expands on those issues and concerns in her new book, What The Wild Seas Can Be: The Future of the World’s Seas. Scales provides us with a fascinating exposition of the pre-historic ocean and the devastating impact of the Anthropocene on ocean life over the last fifty years. Her main concern, however, is the future of the ocean and her new book makes a major contribution to people’s understanding of the repercussions of human activity on ocean life and the measures that need to be taken to protect and secure a better future for the ocean.

Marine biologist Helen Scales’ previous book The Brilliant Abyss: True Tales of Exploring the Deep Sea, Discovering Hidden Life and Selling the Seabed, brilliantly provided us with a glimpse of the wondrous life forms that inhabit the abyss, the deep sea. She also made known her profound concern for the future of ocean life posed by human activity. She now expands on those issues and concerns in her new book, What The Wild Seas Can Be: The Future of the World’s Seas. Scales provides us with a fascinating exposition of the pre-historic ocean and the devastating impact of the Anthropocene on ocean life over the last fifty years. Her main concern, however, is the future of the ocean and her new book makes a major contribution to people’s understanding of the repercussions of human activity on ocean life and the measures that need to be taken to protect and secure a better future for the ocean.