by Scott F. Aikin and Robert B. Talisse

We have noted previously that there are two different phenomena called “polarization.” The first, political polarization, refers to the ideological distance between opposing political parties. When it’s rampant, political rivals share no common ground, and thus cannot find a basis for cooperation. Political polarization certainly poses a problem for democracy. Yet belief polarization is perhaps even more troubling. It is the phenomenon by which interactions among likeminded people result in each adopting more radical versions of their views. In a slogan, interactions with likeminded others transform us into more extreme versions of ourselves.

Part of what makes belief polarization so disconcerting is its ubiquity. It has been extensively studied for more than 50 years, and found to be operative within groups of all kinds, formal and informal. Furthermore, belief polarization does not discriminate between different kinds of belief. Likeminded groups polarize regardless of whether they are discussing banal matters of fact, matters of personal taste, or questions about value. What’s more, the phenomenon operates regardless of the explicit point of the group’s discussion. Likeminded groups polarize when they are trying to decide an action that the group will take; and they polarize also when there is no specific decision to be reached. Finally, the phenomenon is prevalent regardless of group members’ nationality, race, gender, religion, economic status, and level of education.

Our widespread susceptibility to belief polarization raises the question of how it works. Two views immediately suggest themselves, the informational account and the comparison account. Read more »

Madeleine LaRue: It did turn out to be pretty mammoth! How about I tell you, by way of introduction, about the first time I met Bichsel in person. He’d come to read at the Literarisches Colloquium in Berlin, the center of the grand old West Berlin literary establishment. It was November, it was dark and cold, and when he emerged at the back of the room and started walking up toward the stage, wearing the same black leather vest he’s been wearing for the past forty years, I think we were all a little worried about him. He was eighty-two then, and he looked exhausted. It had been a while since he’d been on such an extensive reading tour outside of Switzerland. He got to the stage and settled into his chair. The moderator welcomed him and asked how it felt to be back in Berlin—a simple question, a nice, easy opener. Bichsel still seemed tired, but as he leaned back and said, very slowly, in his lilting Swiss accent, “Ja, ja, Berlin,” his eyes lit up and he launched into a story about his first time in the city, in the early 1960s, and how he got caught in the middle of a bar fight with some people! Who turned out to be Swiss! And they all got thrown out onto the street together, and he’ll never forget it! And ja, ja, Berlin—and from his very first word, we all became like delighted children at Grandfather’s feet, totally enraptured, utterly unwilling to go to bed until we’d heard just one more story, pleeeease? And he himself became younger, full of life, charming and hilarious and genuine and profound.

Madeleine LaRue: It did turn out to be pretty mammoth! How about I tell you, by way of introduction, about the first time I met Bichsel in person. He’d come to read at the Literarisches Colloquium in Berlin, the center of the grand old West Berlin literary establishment. It was November, it was dark and cold, and when he emerged at the back of the room and started walking up toward the stage, wearing the same black leather vest he’s been wearing for the past forty years, I think we were all a little worried about him. He was eighty-two then, and he looked exhausted. It had been a while since he’d been on such an extensive reading tour outside of Switzerland. He got to the stage and settled into his chair. The moderator welcomed him and asked how it felt to be back in Berlin—a simple question, a nice, easy opener. Bichsel still seemed tired, but as he leaned back and said, very slowly, in his lilting Swiss accent, “Ja, ja, Berlin,” his eyes lit up and he launched into a story about his first time in the city, in the early 1960s, and how he got caught in the middle of a bar fight with some people! Who turned out to be Swiss! And they all got thrown out onto the street together, and he’ll never forget it! And ja, ja, Berlin—and from his very first word, we all became like delighted children at Grandfather’s feet, totally enraptured, utterly unwilling to go to bed until we’d heard just one more story, pleeeease? And he himself became younger, full of life, charming and hilarious and genuine and profound.  Having before you an iced mango

Having before you an iced mango

I don’t know anything about music. I make art, and like many artists I listen to music while working. Nearly every kind of music, but mostly metal for those time-to-get-serious moments. Atmospheric black metal with little discernible speech tends to work best, because it provides a setting such that one can become lost in the droning distortions when working on something. The music I like to hear is that which Kant would endorse as sublime – enormous walls of sound that result in a distractedness where one can go undeterred by outside forces. Of course an fMRI could show what is happening in the brain, what psychically galvanizes me while I listen to music in those moments, but I’m less interested in what’s happening to me as much as what’s happening to it: what happens to artworks when produced to a soundtrack?

I don’t know anything about music. I make art, and like many artists I listen to music while working. Nearly every kind of music, but mostly metal for those time-to-get-serious moments. Atmospheric black metal with little discernible speech tends to work best, because it provides a setting such that one can become lost in the droning distortions when working on something. The music I like to hear is that which Kant would endorse as sublime – enormous walls of sound that result in a distractedness where one can go undeterred by outside forces. Of course an fMRI could show what is happening in the brain, what psychically galvanizes me while I listen to music in those moments, but I’m less interested in what’s happening to me as much as what’s happening to it: what happens to artworks when produced to a soundtrack?

On a whim I decided to visit the gently sloping hill where the universe announced itself in 1964, not with a bang but with ambient, annoying noise. It’s the static you saw when you turned on your TV, or at least used to back when analog TVs were a thing. But today there was no noise except for the occasional chirping of birds, the lone car driving off in the distance and a gentle breeze flowing through the trees. A recent trace of rain had brought verdant green colors to the grass. A deer darted into the undergrowth in the distance.

On a whim I decided to visit the gently sloping hill where the universe announced itself in 1964, not with a bang but with ambient, annoying noise. It’s the static you saw when you turned on your TV, or at least used to back when analog TVs were a thing. But today there was no noise except for the occasional chirping of birds, the lone car driving off in the distance and a gentle breeze flowing through the trees. A recent trace of rain had brought verdant green colors to the grass. A deer darted into the undergrowth in the distance.

Sughra Raza. Enlightened, April, 2019.

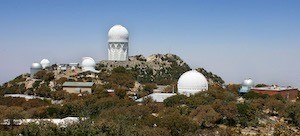

Sughra Raza. Enlightened, April, 2019. When I returned to school after my first marriage ended, I had to decide what to study. I’d been working toward a degree in history when I dropped out of a community college to get married, but I’d always been drawn to astronomy. One of the reasons I chose astronomy over history, or any other option, was that I felt that astronomy contained many of the other things I was interested in. To put it another way, I thought that if I didn’t study astronomy, I would regret it, but if I did study it, I wouldn’t necessarily lose touch with the other things I was interested in because they were all part of astronomy, in one way or another.

When I returned to school after my first marriage ended, I had to decide what to study. I’d been working toward a degree in history when I dropped out of a community college to get married, but I’d always been drawn to astronomy. One of the reasons I chose astronomy over history, or any other option, was that I felt that astronomy contained many of the other things I was interested in. To put it another way, I thought that if I didn’t study astronomy, I would regret it, but if I did study it, I wouldn’t necessarily lose touch with the other things I was interested in because they were all part of astronomy, in one way or another.