by Mindy Clegg

Welcome to the future, which is now the past. As James Gleick argued (in his thoughtful and entertaining book, Time Travel: A History) the concept of the future is now fodder for historical understanding. As Gleick notes in his book, popular culture provides a key insight into how ideas about the future shaped the past, present, and the actual future.1

Pop culture during the twentieth century has long imagined the near and far future. Such imaginings became a running gag for talk show host Conan O’Brien. Back in the late 1990s, he started a new segment on his show, called “In the Year 2000.” It started first with him and his co-host Andy Richter (and later guests he was interviewing) donning collars and lighting up their faces with flashlights, while the band played futuristic sounding music in the background. Then, a round of predictions based on current events, ridiculous and silly predictions, all set to happen in the far off future of the year 2000. This bit continued well into the new millennium. Only during O’Brien’s all too-short stint hosting the famed Tonight Show did the format change to predict events in the year 3000 (with Captain Kirk himself, William Shatner providing a regular voice over—although once it was Lt. Sulu instead, George Takei).

The joke revolved around the idea that the future was already here, but the year “2000” still sounds pretty futuristic. Plus, it plays on how we viewed the future across the breadth of the twentieth century, as culminating in a utopia of technological progress, inevitably leading to social progress. Think Disney’s Epcot Center or Gene Roddenberry’s hopeful, post-scarcity, racially unified vision of the future in Star Trek. But O’Brien also pointed to a new phenomenon, when dates from popular culture in what was once the future recede into the past. I argue in this essay that the future we imagined in the past both shaped the present and contradicts it. This becomes clearest when we examine how some science fiction films or TV shows imagined a future date in our recent past. I’ll take three examples, the first being the classic anime, Neon Genesis Evangelion (set in 2015). The second is Ridley Scott’s classic adaptation of Phillip K. Dick’s novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep, Blade Runner (set in 2019). Last will be two events in the Star Trek universe: one set in our recent past (the Eugenics Wars) and one in the near future (the Bell riots). Read more »

I was always a skinny fuck. Forever the thinnest kid in the class, and for a longtime the second shortest boy (thank you, David Mehler). My stick-figure proportions were the thing of legend. I could suck my stomach in so far that some people swore they could touch the inside of my spine. My uncle used to refer to me as the Biafra Boy, a tasteless reference to the gruesome famine that accompanied the Nigerian Civil War (1967 – 70). In an effort to fatten me up, my grandmother would serve me breakfast cereal with half-and-half instead of milk. It was to no avail. A growth spurt in the 8th grade got me well above the short kids, but my body didn’t fill out. I graduated high school standing five feet, nine and a half inches tall, and weighing less than 120 pounds.

I was always a skinny fuck. Forever the thinnest kid in the class, and for a longtime the second shortest boy (thank you, David Mehler). My stick-figure proportions were the thing of legend. I could suck my stomach in so far that some people swore they could touch the inside of my spine. My uncle used to refer to me as the Biafra Boy, a tasteless reference to the gruesome famine that accompanied the Nigerian Civil War (1967 – 70). In an effort to fatten me up, my grandmother would serve me breakfast cereal with half-and-half instead of milk. It was to no avail. A growth spurt in the 8th grade got me well above the short kids, but my body didn’t fill out. I graduated high school standing five feet, nine and a half inches tall, and weighing less than 120 pounds. Economics. The dismal science. All those numbers and graphs, formulas and derivations, tombstone-sized copies of Paul Samuelson and William Nordhaus’s Macroeconomics (now apparently in its 19th edition), and memories of the detritus that came with them: half-filled coffee cups and overfilled ashtrays, mechanical pencils and HP-45s.

Economics. The dismal science. All those numbers and graphs, formulas and derivations, tombstone-sized copies of Paul Samuelson and William Nordhaus’s Macroeconomics (now apparently in its 19th edition), and memories of the detritus that came with them: half-filled coffee cups and overfilled ashtrays, mechanical pencils and HP-45s.

The opening lines to the French philosopher and mathematician René Descartes’ classic philosophical text, the

The opening lines to the French philosopher and mathematician René Descartes’ classic philosophical text, the  The blog post screams: “If you think 2 + 2 always equals 4, you’re a racist oppressor.”

The blog post screams: “If you think 2 + 2 always equals 4, you’re a racist oppressor.”

“I don’t like Polish people,” he says, and raises an eyebrow suggesting “How could anybody, really?”

“I don’t like Polish people,” he says, and raises an eyebrow suggesting “How could anybody, really?”  are suitable to it. The computer is ontologically ambiguous. Can it think, or only calculate? Is it a brain or only a machine?

are suitable to it. The computer is ontologically ambiguous. Can it think, or only calculate? Is it a brain or only a machine?

Last year we drove across the country. We had one cassette tape to listen to on the entire trip. I don’t remember what it was. —Steven Wright

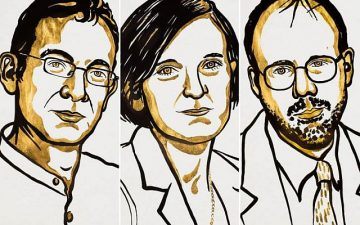

Last year we drove across the country. We had one cassette tape to listen to on the entire trip. I don’t remember what it was. —Steven Wright As a development economist I am celebrating, along with my co-professionals, the award of the Nobel Prize this year to three of our best development economists, Abhijit Banerjee, Esther Duflo and Michael Kremer. Even though the brilliance of these three economists has illuminated a whole range of subjects in our discipline, invariably, the write-ups in the media have referred to their great service to the cause of tackling global poverty, with their experimental approach, particularly the use of Randomized Control Trial (RCT).

As a development economist I am celebrating, along with my co-professionals, the award of the Nobel Prize this year to three of our best development economists, Abhijit Banerjee, Esther Duflo and Michael Kremer. Even though the brilliance of these three economists has illuminated a whole range of subjects in our discipline, invariably, the write-ups in the media have referred to their great service to the cause of tackling global poverty, with their experimental approach, particularly the use of Randomized Control Trial (RCT).

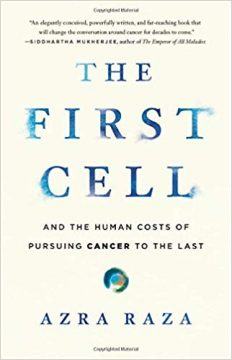

When I was a young attending surgeon on the faculty in the Division of Cardiothoracic Surgery, one of the things I got frequently called for was management of malignant pleural or pericardial effusions. Once a patient develops malignant pleural or pericardial effusion the median survival is only two months, so I would do things that would relieve the acute symptoms and perhaps try to prevent fluid from reaccumulating, but nothing drastic or major. One evening in late October, one of the nurses who had known me called to say that her father was being treated for lung cancer but had to be admitted with a large pleural effusion and that she and her father’s Oncologist would like me to manage it. I met the fine 72-year old retired banker, and while he was short of breath even as he talked, he was in a very upbeat mood. I decided to insert a chest tube to drain the pleural fluid and relieve his symptoms. As I was doing the procedure at the bedside the patient mentioned to me that his oncologist has assured him that once his fluid is out he will start him on a new regimen of chemotherapy and he should expect to live for a few more years. I was disturbed to hear the false hope he was being given.

When I was a young attending surgeon on the faculty in the Division of Cardiothoracic Surgery, one of the things I got frequently called for was management of malignant pleural or pericardial effusions. Once a patient develops malignant pleural or pericardial effusion the median survival is only two months, so I would do things that would relieve the acute symptoms and perhaps try to prevent fluid from reaccumulating, but nothing drastic or major. One evening in late October, one of the nurses who had known me called to say that her father was being treated for lung cancer but had to be admitted with a large pleural effusion and that she and her father’s Oncologist would like me to manage it. I met the fine 72-year old retired banker, and while he was short of breath even as he talked, he was in a very upbeat mood. I decided to insert a chest tube to drain the pleural fluid and relieve his symptoms. As I was doing the procedure at the bedside the patient mentioned to me that his oncologist has assured him that once his fluid is out he will start him on a new regimen of chemotherapy and he should expect to live for a few more years. I was disturbed to hear the false hope he was being given.