by Joan Harvey

On this last Veterans Day, a young friend shared an essay on Facebook by veteran Rory Fanning about his wish that Veterans Day, which celebrates militarism, be changed back to Armistice Day, to celebrate those working for justice and peace. I hadn’t known that Armistice Day, which was established after WWI, had been replaced in 1954 by Veterans Day. Veterans Day, Fanning writes, “instead of looking toward a future of peace, celebrates war ‘heroes’ and encourages others to play the hero themselves. . . going off to kill and be killed in a future war—or one of our government’s current, unending wars.”

My father enlisted the first day America joined WWII, but he almost never talked about his experience. I heard about WWII mostly from my grandparents who were active in the Austrian Resistance, and in my twenties, at the urging of a Native American man I knew, I read book after book on the Holocaust. It is hard not to believe that WW II was one of the few necessary and just wars. But in this war, as in all wars, men were used senselessly, and the experience of the men fighting was often less that of achieving a clear useful goal and more of mismanaged chaos.

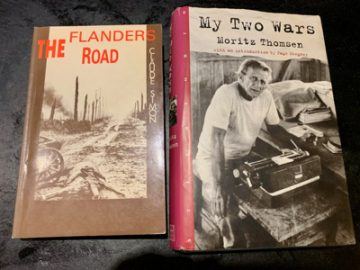

I’ve concurrently been reading a biography of Napoleon and listening to War and Peace. Being neither a war nor a history buff, I read descriptions of battle after battle and look at diagrams of landscapes with arrows and dots, with very little real comprehension of the topography and maneuvers and strategies implemented. But it is impossible to come away from both books without the sense of the millions of lives rapidly, brutally, and very often meaninglessly expended, the millions of young men offering themselves up to be butchered or die of disease or cold or starvation. And these descriptions recalled to my mind two great, but not much read, writers who wrote about fighting in WWII, and who gave me the strongest sense of what combat in that war was like. Read more »

Despite Vonnegut’s strong counsel to babies entering the world, kindness seems to be in short supply. Little wonder. Our news media portray to us a world of power politics, corporate greed, murders, and cruel policies which are anything but kind. Our popular forms of entertainment, much more often than not, are stories about battles that shock and thrill us and gratify our lust for bloody vengeance, leaving no room for wimpy, kind sentiments. Success is advertised to us as requiring harsh discipline, dedication, and focus, and kindness, it appears, need not apply. Even though we all like to give and receive kindnesses, they seem to play no role in our political, social, and cultural economies.

Despite Vonnegut’s strong counsel to babies entering the world, kindness seems to be in short supply. Little wonder. Our news media portray to us a world of power politics, corporate greed, murders, and cruel policies which are anything but kind. Our popular forms of entertainment, much more often than not, are stories about battles that shock and thrill us and gratify our lust for bloody vengeance, leaving no room for wimpy, kind sentiments. Success is advertised to us as requiring harsh discipline, dedication, and focus, and kindness, it appears, need not apply. Even though we all like to give and receive kindnesses, they seem to play no role in our political, social, and cultural economies. In a

In a

A few tall, dreamy-eyed Sikh men were on my plane to Lahore.

A few tall, dreamy-eyed Sikh men were on my plane to Lahore.

I never met Jeremy Spencer, so I can only guess. I suspect he was searching for something. Only 23 years old, perhaps he was unhappy with himself, or the world around him. Perhaps he was scared and craving shelter from the storm. Perhaps he dreamed of what could be, or pined for a grand voyage. Maybe he just got lost.

I never met Jeremy Spencer, so I can only guess. I suspect he was searching for something. Only 23 years old, perhaps he was unhappy with himself, or the world around him. Perhaps he was scared and craving shelter from the storm. Perhaps he dreamed of what could be, or pined for a grand voyage. Maybe he just got lost. In Homo Deus, the 2017 follow-up to his widely read Sapiens, Yuval Noah Harari dismisses the idea of free will in cavalier fashion. Contemporary science, he argues, has proved it to be a fiction. In support of this claim, he offers several arguments.

In Homo Deus, the 2017 follow-up to his widely read Sapiens, Yuval Noah Harari dismisses the idea of free will in cavalier fashion. Contemporary science, he argues, has proved it to be a fiction. In support of this claim, he offers several arguments.

Once upon a time, in a beautiful but endangered forest far far away a prince and princess met, fell in love and married. They were blessed with a hundred children. “I wonder,” said the princess, somewhat exhausted from her exertions, “how best to raise our dear ones to care for each other and their beautiful forest home?” “I have heard,” replied her husband “that reading to children matters.”

Once upon a time, in a beautiful but endangered forest far far away a prince and princess met, fell in love and married. They were blessed with a hundred children. “I wonder,” said the princess, somewhat exhausted from her exertions, “how best to raise our dear ones to care for each other and their beautiful forest home?” “I have heard,” replied her husband “that reading to children matters.”

Wine is a living, dynamically changing, energetic organism. Although it doesn’t quite satisfy strict biological criteria for life, wine exhibits constant, unpredictable variation. It has a developmental trajectory of its own that resists human intentions and an internal structure that facilitates exchange with the external environment thus maintaining a process similar to homeostasis. Organisms are disposed to respond to changes in the environment in ways that do not threaten their integrity. Winemakers build this capacity for vitality in the wines they make.

Wine is a living, dynamically changing, energetic organism. Although it doesn’t quite satisfy strict biological criteria for life, wine exhibits constant, unpredictable variation. It has a developmental trajectory of its own that resists human intentions and an internal structure that facilitates exchange with the external environment thus maintaining a process similar to homeostasis. Organisms are disposed to respond to changes in the environment in ways that do not threaten their integrity. Winemakers build this capacity for vitality in the wines they make.