by Emrys Westacott

In Homo Deus, the 2017 follow-up to his widely read Sapiens, Yuval Noah Harari dismisses the idea of free will in cavalier fashion. Contemporary science, he argues, has proved it to be a fiction. In support of this claim, he offers several arguments.

In Homo Deus, the 2017 follow-up to his widely read Sapiens, Yuval Noah Harari dismisses the idea of free will in cavalier fashion. Contemporary science, he argues, has proved it to be a fiction. In support of this claim, he offers several arguments.

- Everything we do is fully determined by our “genes, hormones, and neurons,” and these “obey the same physical and chemical laws governing the rest of reality.” So from a scientific point of view, if we ask why a man performed any act, “answering ‘Because he chose to’ doesn’t cut the mustard. Instead, geneticists and brain scientists provide a much more detailed answer: ‘He did it due to such-and-such electro-chemical processes in the brain that were shaped by a particular genetic make-up, which in turn reflect evolutionary pressures coupled with random mutations.”[1]

- The concept of free will is incompatible with the theory of evolution. According to Darwin’s theory, we came to be what we are by passing on genes that proved useful in the struggle to survive. If human actions (e.g. eating and mating) were freely chosen, then we couldn’t explain our evolution in terms of natural selection.

- Recent laboratory research proves that our feeling that we make free choices is an illusion. Subjects whose brains are being monitored are told to press one of two switches. They think they are making a free choice; but a scientist watching a brain scanner can predict which switch they will press before the subject is even aware of having made a choice. This shows, says Harari, that “I don’t choose my desires. I only feel them, and act accordingly.”[2]

- The idea of free will is bound up with the idea of an individual self that constitutes the inner essence of each human being. This modern notion of the self is really just a hangover from the religious concept of the soul. But all these notions–soul, self, essence–are outmoded; “so to ask, ‘How does the self choose its desires?’ …[is] like asking a bachelor, ‘How does your wife choose her clothes?’ In reality there is only a stream of consciousness, and desires arise and pass away within this stream, but there is no permanent self that owns the desires…”[3]

Harari advances these arguments with great confidence. Yet they are far from conclusive. Read more »

Once upon a time, in a beautiful but endangered forest far far away a prince and princess met, fell in love and married. They were blessed with a hundred children. “I wonder,” said the princess, somewhat exhausted from her exertions, “how best to raise our dear ones to care for each other and their beautiful forest home?” “I have heard,” replied her husband “that reading to children matters.”

Once upon a time, in a beautiful but endangered forest far far away a prince and princess met, fell in love and married. They were blessed with a hundred children. “I wonder,” said the princess, somewhat exhausted from her exertions, “how best to raise our dear ones to care for each other and their beautiful forest home?” “I have heard,” replied her husband “that reading to children matters.”

Wine is a living, dynamically changing, energetic organism. Although it doesn’t quite satisfy strict biological criteria for life, wine exhibits constant, unpredictable variation. It has a developmental trajectory of its own that resists human intentions and an internal structure that facilitates exchange with the external environment thus maintaining a process similar to homeostasis. Organisms are disposed to respond to changes in the environment in ways that do not threaten their integrity. Winemakers build this capacity for vitality in the wines they make.

Wine is a living, dynamically changing, energetic organism. Although it doesn’t quite satisfy strict biological criteria for life, wine exhibits constant, unpredictable variation. It has a developmental trajectory of its own that resists human intentions and an internal structure that facilitates exchange with the external environment thus maintaining a process similar to homeostasis. Organisms are disposed to respond to changes in the environment in ways that do not threaten their integrity. Winemakers build this capacity for vitality in the wines they make.

I was always a skinny fuck. Forever the thinnest kid in the class, and for a longtime the second shortest boy (thank you, David Mehler). My stick-figure proportions were the thing of legend. I could suck my stomach in so far that some people swore they could touch the inside of my spine. My uncle used to refer to me as the Biafra Boy, a tasteless reference to the gruesome famine that accompanied the Nigerian Civil War (1967 – 70). In an effort to fatten me up, my grandmother would serve me breakfast cereal with half-and-half instead of milk. It was to no avail. A growth spurt in the 8th grade got me well above the short kids, but my body didn’t fill out. I graduated high school standing five feet, nine and a half inches tall, and weighing less than 120 pounds.

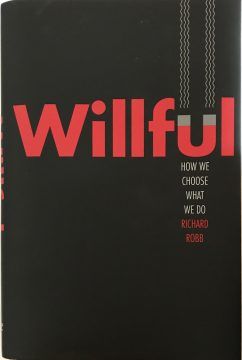

I was always a skinny fuck. Forever the thinnest kid in the class, and for a longtime the second shortest boy (thank you, David Mehler). My stick-figure proportions were the thing of legend. I could suck my stomach in so far that some people swore they could touch the inside of my spine. My uncle used to refer to me as the Biafra Boy, a tasteless reference to the gruesome famine that accompanied the Nigerian Civil War (1967 – 70). In an effort to fatten me up, my grandmother would serve me breakfast cereal with half-and-half instead of milk. It was to no avail. A growth spurt in the 8th grade got me well above the short kids, but my body didn’t fill out. I graduated high school standing five feet, nine and a half inches tall, and weighing less than 120 pounds. Economics. The dismal science. All those numbers and graphs, formulas and derivations, tombstone-sized copies of Paul Samuelson and William Nordhaus’s Macroeconomics (now apparently in its 19th edition), and memories of the detritus that came with them: half-filled coffee cups and overfilled ashtrays, mechanical pencils and HP-45s.

Economics. The dismal science. All those numbers and graphs, formulas and derivations, tombstone-sized copies of Paul Samuelson and William Nordhaus’s Macroeconomics (now apparently in its 19th edition), and memories of the detritus that came with them: half-filled coffee cups and overfilled ashtrays, mechanical pencils and HP-45s.

The opening lines to the French philosopher and mathematician René Descartes’ classic philosophical text, the

The opening lines to the French philosopher and mathematician René Descartes’ classic philosophical text, the  The blog post screams: “If you think 2 + 2 always equals 4, you’re a racist oppressor.”

The blog post screams: “If you think 2 + 2 always equals 4, you’re a racist oppressor.”