by Abigail Akavia

On permanent display in the MFA in Boston is a bust by Oskar Kokoschka, “Self-Portrait as a Warrior.” The sculpture is a dramatic head with bulging features: bridge of the nose, cheek bones, and creased brows. The eyeballs are painted azure blue, the parts around them bright orange. The head’s wrinkled features are highlighted by an unnatural yellow and raw red, which make it look like exposed flesh. The mouth is open. It is this last feature in particular that I found striking: the man portrayed lets out a “violent scream,” as Kokoschka himself puts it in his biography. The portrait, ridiculed when it was first shown in 1909 and later condemned by the Nazi regime as “degenerate,” is an image of torment. This artist-warrior figure of anguish, and the question whether (or how) he is giving voice to his suffering, reminded me of the ancient Greek hero Philoctetes.

A famed archer, Philoctetes was one of the warriors that embarked on the initial expedition against Troy. On the way, he was bit on the foot by a snake. The wound festered and became putrid; Philoctetes screamed in pain so badly that the fleet could not carry out the required sacrifices to the gods. Philoctetes’ suffering presence, in short, was so repulsive and disruptive that the Greeks had to get rid of him. They abandoned him on the island Lemnos, where he remained for ten years, periodically visited by bouts of pain. In the version of his story that has come down to us, a tragedy by Sophocles first performed in 409 BCE, Lemnos is uninhabited. The only thing keeping Philoctetes alive on this desolate place is a magical bow he inherited from his friend Heracles (i.e. the legendary Hercules), with which he preys on wild beasts and birds. Ten years after first leaving him there to fend for himself, the Greeks learn by prophecy that Philoctetes and his bow are necessary to take Troy down. Odysseus sets out to Lemnos to bring him back, with the help of the young Neoptolemus, son of Achilles. Odysseus, forever conniving, deduces rightly that Philoctetes would sooner die than help the Greeks, and concocts a scheme in which it is Neoptolemus’ job to trick Philoctetes into joining him.

To make a long story short, things do not quite go as planned, especially from the moment Neoptolemus witnesses Philoctetes’ excruciating pain. Sophocles’ play is a plot-twisting, complex exploration of the power of language in its various manifestations—sophistry, lies, pleas, inarticulate cries, and poetic invocations, to name some of the drama’s expressive linguistic media. What becomes of humanity when language is used to defy its proclaimed ends? Can language help restore trust and reintegrate into human community a man that has been so traumatized, physically and emotionally, that he can no longer envision camaraderie—no longer imagine any existence other than his beastly exile? Can this trauma be voiced, and responded to, in language? Read more »

I could not believe my luck when I woke up this morning. It had rained last night, but this morning the sky was blue the breeze gentle,and the wild grass along the smelly sluggish, open sewer that meanders through the swanky Defense Housing Authority—home to lush golf courses and palatial villas—past the gates of the elite Lahore University of Management Sciences, was audaciously green. The mango tree in the front yard of my mother’s house—quiet after a fertile summer of exuberant fruiting—balances the crow’s nest full of chattering chicks in its gently swaying branches. All God’s creations bask in the mellow sunshine. No more the snow and ice and cold of Eastern US. For these weeks, it’s going to be this bliss in Lahore. I was glad to be me, and to be alive. I say to myself “Thank God I am on this side of the earth, rather than under it.” What a beautiful world. So much to see and so much to do. I could live like this for a hundred years like William Hazlitt, who claimed to have spent his life “reading books, looking at pictures, going to plays, hearing, thinking, writing on what pleased me best.” I’ll add eating to that list, at the top of it, fried eggs and buttered toast.

I could not believe my luck when I woke up this morning. It had rained last night, but this morning the sky was blue the breeze gentle,and the wild grass along the smelly sluggish, open sewer that meanders through the swanky Defense Housing Authority—home to lush golf courses and palatial villas—past the gates of the elite Lahore University of Management Sciences, was audaciously green. The mango tree in the front yard of my mother’s house—quiet after a fertile summer of exuberant fruiting—balances the crow’s nest full of chattering chicks in its gently swaying branches. All God’s creations bask in the mellow sunshine. No more the snow and ice and cold of Eastern US. For these weeks, it’s going to be this bliss in Lahore. I was glad to be me, and to be alive. I say to myself “Thank God I am on this side of the earth, rather than under it.” What a beautiful world. So much to see and so much to do. I could live like this for a hundred years like William Hazlitt, who claimed to have spent his life “reading books, looking at pictures, going to plays, hearing, thinking, writing on what pleased me best.” I’ll add eating to that list, at the top of it, fried eggs and buttered toast.

American writer Rebecca Solnit laments that few writers have had quite as much scrutiny directed toward their laundry habits as Transcendentalist writer Henry David Thoreau, best known for his 1854 memoir Walden. “Only Henry David Thoreau,” she claims in Orion Magazine’s article “Mysteries of Thoreau, Unsolved,” “has been tried in the popular imagination and found wanting for his cleaning arrangements.”

American writer Rebecca Solnit laments that few writers have had quite as much scrutiny directed toward their laundry habits as Transcendentalist writer Henry David Thoreau, best known for his 1854 memoir Walden. “Only Henry David Thoreau,” she claims in Orion Magazine’s article “Mysteries of Thoreau, Unsolved,” “has been tried in the popular imagination and found wanting for his cleaning arrangements.” Among the best books I’ve read about wine are the two by wine importer Terry Theise.

Among the best books I’ve read about wine are the two by wine importer Terry Theise.

I saw Joker last week. I think it’s an excellent film. But the two friends I was with, whose tastes often overlap with my own, really hated it, and we spent the ensuing 90 minutes examining and debating the film. Critics are likewise fiercely divided. Towards the end of our conversation, one friend admitted that, love it or hate it, the film evokes strong reactions; it’s difficult to ignore.

I saw Joker last week. I think it’s an excellent film. But the two friends I was with, whose tastes often overlap with my own, really hated it, and we spent the ensuing 90 minutes examining and debating the film. Critics are likewise fiercely divided. Towards the end of our conversation, one friend admitted that, love it or hate it, the film evokes strong reactions; it’s difficult to ignore.

The terror of the unforeseen is what the science of history hides, turning a disaster into an epic. —Philip Roth, The Plot Against America

The terror of the unforeseen is what the science of history hides, turning a disaster into an epic. —Philip Roth, The Plot Against America “What is hidden is for us Westerners more ‘true’ than what is visible,” Roland Barthes proposed, in Camera Lucida, his phenomenology of the photograph, almost forty years ago. In the decades since, the internet, nanotechnology, and viral marketing have challenged his privileging of the unseen over the seen by developing a culture of total exposure, heralding the death of interiority and celebrating the cult of instant celebrity. The icon of this movement, the selfie, is now produced and displayed, in endless daily iterations, in a ritual staging of eyewitness testimony to the festival of self-fashioning.

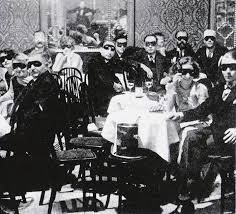

“What is hidden is for us Westerners more ‘true’ than what is visible,” Roland Barthes proposed, in Camera Lucida, his phenomenology of the photograph, almost forty years ago. In the decades since, the internet, nanotechnology, and viral marketing have challenged his privileging of the unseen over the seen by developing a culture of total exposure, heralding the death of interiority and celebrating the cult of instant celebrity. The icon of this movement, the selfie, is now produced and displayed, in endless daily iterations, in a ritual staging of eyewitness testimony to the festival of self-fashioning.