by Robert Frodeman and Evelyn Brister

People sometimes express confusion about what public philosophy is. We see the point as straightforward: it’s a matter of location. Public philosophy consists of all those efforts that aren’t centered on university life. Public philosophers write op-eds for newspapers, work on disability issues and penal reform, serve on expert committees for government agencies, teach in prisons and schools, and help community groups balance considerations of justice with economic development. But while the possibilities for public philosophy are infinite, the distinction is clear: are your attentions directed toward other philosophers? That’s academic philosophy. Are your efforts aimed at the wider world? That’s public philosophy.

People sometimes express confusion about what public philosophy is. We see the point as straightforward: it’s a matter of location. Public philosophy consists of all those efforts that aren’t centered on university life. Public philosophers write op-eds for newspapers, work on disability issues and penal reform, serve on expert committees for government agencies, teach in prisons and schools, and help community groups balance considerations of justice with economic development. But while the possibilities for public philosophy are infinite, the distinction is clear: are your attentions directed toward other philosophers? That’s academic philosophy. Are your efforts aimed at the wider world? That’s public philosophy.

We’re pluralists in our attitude toward public philosophy: all of these varieties are useful in a world that too often assumes that the answers to societal questions come down to science or economics. But we want to emphasize one particular strain of public philosophy: what we call field philosophy. By analogy with field science, field philosophers work on-site with non-philosophers over an extended period of time. These are philosophers who are not simply writing about public problems but are engaged in projects, working alongside people as they confront real-world issues.

In a recent 3QD piece, Scott F. Aikin and Robert B. Talisse sound dubious about the usefulness of public philosophy. They claim that public philosophy has a distressing retrospective quality: by commenting on a situation philosophers are likely to affect that situation, and so are engaged in a continual process of catch-up. We grant the point, but we fail to see it as a problem. Public philosophy does not only consist of external, after-the-fact historical commentary. Particularly in the case of field philosophy, it actively participates in making sense of unfolding cultural events and reveals the conflicting pulls that make for difficult decisions. This iterative loop forms part of the dynamics of thinking, where an account adjusts to changed circumstances. The philosopher thinks with the scientist, the engineer, the businessperson, or the stakeholders’ group. Adjustment in the face of real-world conditions is how things are supposed to work. Read more »

1.

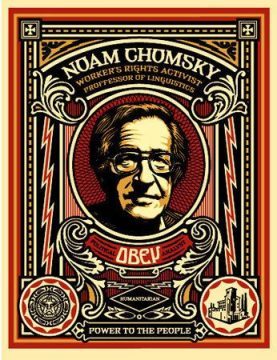

1. A lot has changed since 1967, the year Noam Chomsky published “The Responsibility of Intellectuals.” His essay threw damning shade at the intelligentsia—particularly those in the social and political sciences—as well as those that supported what he called the “cult of expertise,” an ideological formation of professors, philosophers, scientists, military strategists, economists, technocrats, and foreign policy wonks, some of who believed the general public was ill-equipped (i.e., too stupid) to make decisions about the Vietnam war without experts to make it for them. For others in this cult, the public represented a real threat to established power and its operations in Vietnam, not because they were too stupid to understand foreign policy, but because they would understand it all too well. They had a sense that the public, if they learned the facts, wouldn’t support their foreign policy. Of course, in retrospect, we know that this is exactly what happened. Once the facts of the operation leaked out or were exposed by Chomsky and others like him, the majority of people disagreed with the “experts.” Soon there were new experts to provide rationalizations for why and how the old experts got it wrong, but not before a groundswell of popular protest and resistance turned the political tide and gave a glimpse at the power of everyday people—the “excesses of democracy”—to control the fate of the nation and the world.

A lot has changed since 1967, the year Noam Chomsky published “The Responsibility of Intellectuals.” His essay threw damning shade at the intelligentsia—particularly those in the social and political sciences—as well as those that supported what he called the “cult of expertise,” an ideological formation of professors, philosophers, scientists, military strategists, economists, technocrats, and foreign policy wonks, some of who believed the general public was ill-equipped (i.e., too stupid) to make decisions about the Vietnam war without experts to make it for them. For others in this cult, the public represented a real threat to established power and its operations in Vietnam, not because they were too stupid to understand foreign policy, but because they would understand it all too well. They had a sense that the public, if they learned the facts, wouldn’t support their foreign policy. Of course, in retrospect, we know that this is exactly what happened. Once the facts of the operation leaked out or were exposed by Chomsky and others like him, the majority of people disagreed with the “experts.” Soon there were new experts to provide rationalizations for why and how the old experts got it wrong, but not before a groundswell of popular protest and resistance turned the political tide and gave a glimpse at the power of everyday people—the “excesses of democracy”—to control the fate of the nation and the world. Chomsky has consistently been confident that people who were not considered experts in foreign affairs were as capable if not more so to decide what was right and wrong without the expert as a guide. This is one of the things that continues to make Chomsky such a threat to the established order. He has faith in the public’s ability to think critically (i.e., reasonably, morally, and logically) about foreign affairs and other governmental actions at the local and national levels. For Chomsky, the promise of democracy begins and ends with the people. He does not have the same confidence that those in positions of power will give the public the facts so that they can make good and reasonable decisions. But this does not mean that Chomsky uncritically embraces the public simply because it is the public. He does not support, nor has he ever, the cult of willful ignorance; that is, those members of the public—experts, intellectuals or laypeople—who, as Kierkegaard wrote, “refuse to believe what is true.”

Chomsky has consistently been confident that people who were not considered experts in foreign affairs were as capable if not more so to decide what was right and wrong without the expert as a guide. This is one of the things that continues to make Chomsky such a threat to the established order. He has faith in the public’s ability to think critically (i.e., reasonably, morally, and logically) about foreign affairs and other governmental actions at the local and national levels. For Chomsky, the promise of democracy begins and ends with the people. He does not have the same confidence that those in positions of power will give the public the facts so that they can make good and reasonable decisions. But this does not mean that Chomsky uncritically embraces the public simply because it is the public. He does not support, nor has he ever, the cult of willful ignorance; that is, those members of the public—experts, intellectuals or laypeople—who, as Kierkegaard wrote, “refuse to believe what is true.”

If you have read reports about Mr. Barr’s remarks, you probably already know they have been criticized for their ferocious partisanship. There is unquestionably a considerable amount of energy devoted to critiquing those who get in President Trump’s way (Congress, the federal courts, Progressives, and private citizens who exercise their right of free speech). But M

If you have read reports about Mr. Barr’s remarks, you probably already know they have been criticized for their ferocious partisanship. There is unquestionably a considerable amount of energy devoted to critiquing those who get in President Trump’s way (Congress, the federal courts, Progressives, and private citizens who exercise their right of free speech). But M Theodore M. Bernstein – Miss Thistlebottom’s Hobgoblins: The Careful Writer’s Guide to the Taboos, Bugbears, and Outmoded Rules of English Usage (1971)

Theodore M. Bernstein – Miss Thistlebottom’s Hobgoblins: The Careful Writer’s Guide to the Taboos, Bugbears, and Outmoded Rules of English Usage (1971)

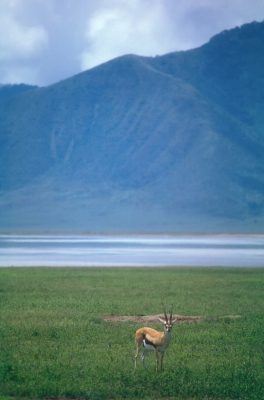

Godfrey points the Land Rover toward Ngorongoro Crater. The road is fine to lull the unwary, but before you know it there is one lane, then no tarmac, then mud and potholes and empty hills.

Godfrey points the Land Rover toward Ngorongoro Crater. The road is fine to lull the unwary, but before you know it there is one lane, then no tarmac, then mud and potholes and empty hills.

Europeans spent 400 years killing, raping, lying to, and robbing Indigenous Americans. And then, when they’d taken most everything they wanted, they turned Native peoples into tokens, costumes, mascots, and fashion accessories. Like most fashion trends, it’s gone in cycles.

Europeans spent 400 years killing, raping, lying to, and robbing Indigenous Americans. And then, when they’d taken most everything they wanted, they turned Native peoples into tokens, costumes, mascots, and fashion accessories. Like most fashion trends, it’s gone in cycles.

Childrearing practices in the United States underwent a radical alteration during a period from the last decade of the nineteenth century through the first few decades of the twentieth. In 1929, psychologists William Blatz and Helen Bott looked back on the changes they credited to Dr. Luther Emmett Holt, whose childcare manual was first published in 1894 and continued to come out in new editions every few years:

Childrearing practices in the United States underwent a radical alteration during a period from the last decade of the nineteenth century through the first few decades of the twentieth. In 1929, psychologists William Blatz and Helen Bott looked back on the changes they credited to Dr. Luther Emmett Holt, whose childcare manual was first published in 1894 and continued to come out in new editions every few years: I recently read Jill Lepore’s

I recently read Jill Lepore’s  At the heart of French existentialism – and especially the version associated with its most famous representative, Jean Paul Sartre – was the notion of radical freedom. On this view, when we choose, we choose our values and thus what kind of person we are going to be. Nothing can prescribe to us what we ought to value, and the responsibility of freedom is to accept this fact of the human condition without falling into the ‘bad faith’ which would deny it. The moment of existentialism may have passed, but the view that we are radical choosers of our values persists in many quarters, and so I want to consider how well this idea holds up, and what an alternative to it might look like.

At the heart of French existentialism – and especially the version associated with its most famous representative, Jean Paul Sartre – was the notion of radical freedom. On this view, when we choose, we choose our values and thus what kind of person we are going to be. Nothing can prescribe to us what we ought to value, and the responsibility of freedom is to accept this fact of the human condition without falling into the ‘bad faith’ which would deny it. The moment of existentialism may have passed, but the view that we are radical choosers of our values persists in many quarters, and so I want to consider how well this idea holds up, and what an alternative to it might look like.