Leroy “Lee” Edward Hood is a Senior Vice President and Chief Science Officer, Providence St. Joseph Health; Chief Strategy Officer, Co-founder and Professor at Institute for Systems Biology. Previously Dr. Hood served on the faculties at the California Institute of Technology (Caltech) and the University of Washington. Dr. Hood is a world-renowned scientist and a recipient of the National Medal of Science in 2011. He has developed ground-breaking scientific instruments which made possible major advances in the biological sciences and the medical sciences. These include the first gas phase protein sequencer, a DNA synthesizer, a peptide synthesizer, the first automated DNA sequencer, ink-jet oligonucleotide technology for synthesizing DNA and nanostring technology for analyzing single molecules of DNA and RNA. He is a member of the National Academy of Sciences, the National Academy of Engineering, and the National Academy of Medicine. Of the more than 6,000 scientists worldwide who belong to one or more of these academies, Dr. Hood is one of only 20 people elected to all three.

Azra Raza, author of The First Cell: And the Human Costs of Pursuing Cancer to the Last, oncologist and professor of medicine at Columbia University, and 3QD editor, decided to speak to more than 20 leading cancer investigators and ask each of them the same five questions listed below. She videotaped the interviews and over the next months we will be posting them here one at a time each Monday. Please keep in mind that Azra and the rest of us at 3QD neither endorse nor oppose any of the answers given by the researchers as part of this project. Their views are their own. One can browse all previous interviews here.

1. We were treating acute myeloid leukemia (AML) with 7+3 (7 days of the drug cytosine arabinoside and 3 days of daunomycin) in 1977. We are still doing the same in 2019. What is the best way forward to change it by 2028?

2. There are 3.5 million papers on cancer, 135,000 in 2017 alone. There is a staggering disconnect between great scientific insights and translation to improved therapy. What are we doing wrong?

3. The fact that children respond to the same treatment better than adults seems to suggest that the cancer biology is different and also that the host is different. Since most cancers increase with age, even having good therapy may not matter as the host is decrepit. Solution?

4. You have great knowledge and experience in the field. If you were given limitless resources to plan a cure for cancer, what will you do?

5. Offering patients with advanced stage non-curable cancer, palliative but toxic treatments is a service or disservice in the current therapeutic landscape?

Gibraltar in the background, I pose sideways, wearing a Spanish Chrysanthemum claw in my hair, gitana style, taking a dare from my husband. The photo is from an August afternoon, captured in the sun’s manic glare. My shadow in profile, with the oversized flower behind my ear, mirrors the shape of Gibraltar, Jabl ut Tariq or “Tariq’s rock.” An actual visit to Gibraltar is more than a decade ahead in the future. I would spend years researching the civilization of al Andalus (Muslim Spain, 711-1492) and publish a book about the convivencia of the Abrahamic people before finally setting foot on Gibraltar. “In Cordoba,” I write, “I’m inside the tremor of exile— the primeval, paramount home of poetry” and that “I am drawn to the world of al Andalus because it is a gift of exiles, a celebration of the cusp and of plural identities, the meeting point of three continents and three faiths, where the drama of boundaries and their blurring took place.” At the heart of this pursuit is my own story, one that is illuminated only recently when I see in Gibraltar more facets of my own exile and encounter with borders.

Gibraltar in the background, I pose sideways, wearing a Spanish Chrysanthemum claw in my hair, gitana style, taking a dare from my husband. The photo is from an August afternoon, captured in the sun’s manic glare. My shadow in profile, with the oversized flower behind my ear, mirrors the shape of Gibraltar, Jabl ut Tariq or “Tariq’s rock.” An actual visit to Gibraltar is more than a decade ahead in the future. I would spend years researching the civilization of al Andalus (Muslim Spain, 711-1492) and publish a book about the convivencia of the Abrahamic people before finally setting foot on Gibraltar. “In Cordoba,” I write, “I’m inside the tremor of exile— the primeval, paramount home of poetry” and that “I am drawn to the world of al Andalus because it is a gift of exiles, a celebration of the cusp and of plural identities, the meeting point of three continents and three faiths, where the drama of boundaries and their blurring took place.” At the heart of this pursuit is my own story, one that is illuminated only recently when I see in Gibraltar more facets of my own exile and encounter with borders.

Most people associate the Cold War with several decades of intense political and economic competition between the United States and Soviet Union. A constant back and forth punctuated by dramatic moments such as the Berlin Airlift, the Berlin Wall, the arms race, the space race, the Bay of Pigs, the Cuban Missile Crisis, Nixon’s visit to China, the Olympic boycotts, “Mr. Gorbachev, tear down this wall!” and eventually the collapse of the Soviet system.

Most people associate the Cold War with several decades of intense political and economic competition between the United States and Soviet Union. A constant back and forth punctuated by dramatic moments such as the Berlin Airlift, the Berlin Wall, the arms race, the space race, the Bay of Pigs, the Cuban Missile Crisis, Nixon’s visit to China, the Olympic boycotts, “Mr. Gorbachev, tear down this wall!” and eventually the collapse of the Soviet system.

Where is philosophy in public life? Can we point to how the world in 2020 is different than it was in 2010 or 1990 because of philosophical research?

Where is philosophy in public life? Can we point to how the world in 2020 is different than it was in 2010 or 1990 because of philosophical research?

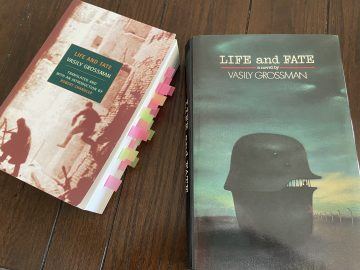

On June 22, 1941, Nazi Germany attacked the Soviet Union in a typhoon of steel and firepower without precedent in history. In spite of telltale signs and repeated warnings, Joseph Stalin who had indulged in wishful thinking was caught completely off guard. He was so stunned that he became almost catatonic, shutting himself in his dacha, not even coming out to make a formal announcement. It was days later that he regained his composure and spoke to the nation from the heart, awakening a decrepit albeit enormous war machine that would change the fate of tens of millions forever. By this time, the German juggernaut had advanced almost to the doors of Moscow, and the Soviet Union threw everything that it had to stop Hitler from breaking down the door and bringing the whole rotten structure on the Russian people’s heads, as the Führer had boasted of doing.

On June 22, 1941, Nazi Germany attacked the Soviet Union in a typhoon of steel and firepower without precedent in history. In spite of telltale signs and repeated warnings, Joseph Stalin who had indulged in wishful thinking was caught completely off guard. He was so stunned that he became almost catatonic, shutting himself in his dacha, not even coming out to make a formal announcement. It was days later that he regained his composure and spoke to the nation from the heart, awakening a decrepit albeit enormous war machine that would change the fate of tens of millions forever. By this time, the German juggernaut had advanced almost to the doors of Moscow, and the Soviet Union threw everything that it had to stop Hitler from breaking down the door and bringing the whole rotten structure on the Russian people’s heads, as the Führer had boasted of doing.

Ryan Ruby is a novelist, translator, critic, and poet who lives, as I do, in Berlin. Back in the summer of 2018, I attended an event at TOP, an art space in Neukölln, where along with journalist Ben Mauk and translator Anne Posten, his colleagues at the Berlin Writers’ Workshop, he was reading from work in progress. Ryan read from a project he called Context Collapse, which, if I remember correctly, he described as a “poem containing the history of poetry.” But to my ears, it sounded more like an academic paper than a poem, with jargon imported from disciplines such as media theory, economics, and literary criticism. It even contained statistics, citations from previous scholarship, and explanatory footnotes, written in blank verse, which were printed out, shuffled up, and distributed to the audience. Throughout the reading, Ryan would hold up a number on a sheet of paper corresponding to the footnote in the text, and a voice from the audience would read it aloud, creating a spatialized, polyvocal sonic environment as well as, to be perfectly honest, a feeling of information overload. Later, I asked him to send me the excerpt, so I could delve deeper into what he had written at a slower pace than readings typically afford—and I’ve been looking forward to seeing the finished project ever since. And now that it is, I am publishing the first suite of excerpts from Context Collapse at Statorec, where I am editor-in-chief.

Ryan Ruby is a novelist, translator, critic, and poet who lives, as I do, in Berlin. Back in the summer of 2018, I attended an event at TOP, an art space in Neukölln, where along with journalist Ben Mauk and translator Anne Posten, his colleagues at the Berlin Writers’ Workshop, he was reading from work in progress. Ryan read from a project he called Context Collapse, which, if I remember correctly, he described as a “poem containing the history of poetry.” But to my ears, it sounded more like an academic paper than a poem, with jargon imported from disciplines such as media theory, economics, and literary criticism. It even contained statistics, citations from previous scholarship, and explanatory footnotes, written in blank verse, which were printed out, shuffled up, and distributed to the audience. Throughout the reading, Ryan would hold up a number on a sheet of paper corresponding to the footnote in the text, and a voice from the audience would read it aloud, creating a spatialized, polyvocal sonic environment as well as, to be perfectly honest, a feeling of information overload. Later, I asked him to send me the excerpt, so I could delve deeper into what he had written at a slower pace than readings typically afford—and I’ve been looking forward to seeing the finished project ever since. And now that it is, I am publishing the first suite of excerpts from Context Collapse at Statorec, where I am editor-in-chief.