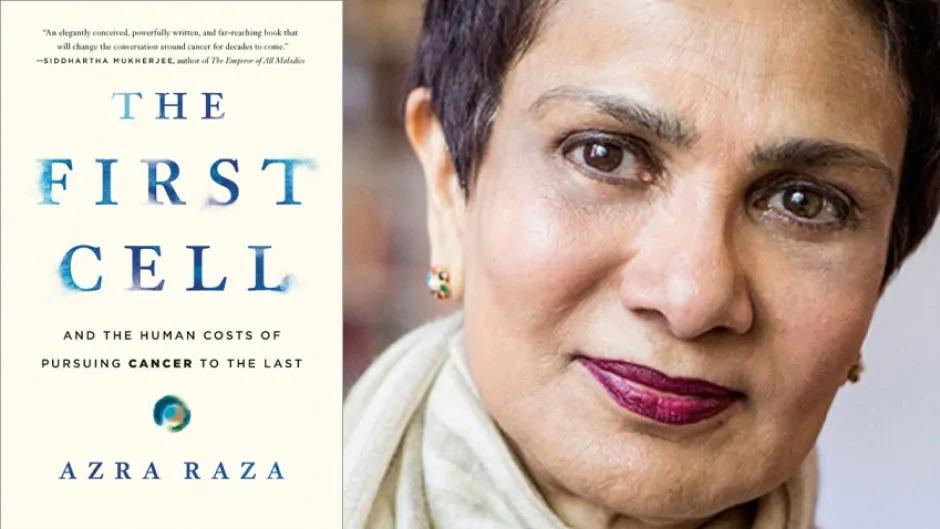

Editor’s Note: This is a letter sent by Dr. Audeh to my sister about her recent book, The First Cell: And the Human Costs of Pursuing Cancer to the Last, and I am publishing it here as a review with his permission.

by M. William Audeh

May 26, 2020

May 26, 2020

Dear Azra,

I am happy to inform you that upon the end our phone conversation, I opened your book, which had been on my Kindle since its publication, and read it over the long weekend.

My apologies for not having read it earlier, but I had my reasons, which I will explain below. However, let me begin by saying that I thoroughly enjoyed your book, not least because your passionate voice comes through the pages so clearly in your writing. I feel as if I have had the privilege of spending several evenings in your lucid company, discussing these fundamental scientific ideas and sharing the heartfelt sorrows. It is eloquent and wonderfully written; a deeply passionate yet sharply rationale argument and memoir. Congratulations!

I will confess, that although I was quite interested to read your book, having spoken with you about its inception, development and impending publication, I was ultimately hesitant. My reluctance stemmed from two regrettable impulses, about which I am not proud, but will readily admit to you, as a dear friend. One was simple jealousy, that you had written and published a book which expressed your long-held beliefs, and anger at myself, for not having found the time and energy to do so myself. Perhaps reading your book will now inspire me to write my own. The other source of my hesitancy was the belief, not entirely unfounded, that I would find myself disagreeing with you on many points of your discourse and did not want to experience that discomfort in relation to you as a friend and colleague. In truth, I am in agreement with you on so very many aspects of your book, that I feel foolish in having held that concern. However, now that I have read your work, and understand the manner in which you have chosen to lay out your argument, I would like to express my thoughts on what you have written. Read more »

Have a look at the

Have a look at the  In thinking about knowledge and consciousness, it is just about irresistible to distinguish between the basic facts of what we observe and interpretations or beliefs about those facts. You and I see the same glass of water – maybe our perceptions of the glass are nearly identical – and yet you see it has half full while I see it as half empty. We look at the same economic reports, and you find reason to celebrate while I find cause to worry. We see an artificial satellite in orbit, and you see it an incursion of government and industry into space while I see it as a glory of science and engineering. And so on – it seems obvious that there is a divide between what everyone can plainly see and what’s a matter of interpretation.

In thinking about knowledge and consciousness, it is just about irresistible to distinguish between the basic facts of what we observe and interpretations or beliefs about those facts. You and I see the same glass of water – maybe our perceptions of the glass are nearly identical – and yet you see it has half full while I see it as half empty. We look at the same economic reports, and you find reason to celebrate while I find cause to worry. We see an artificial satellite in orbit, and you see it an incursion of government and industry into space while I see it as a glory of science and engineering. And so on – it seems obvious that there is a divide between what everyone can plainly see and what’s a matter of interpretation.

When I feel myself becoming irritable, disheartened, or just plain fed-up with life during the pandemic, I find it helpful to conduct a thought-experiment familiar to the ancient Stoics. I reflect on how much I have to be grateful for, and how things could be so much worse. That prompts the more general question: Who are the fortunate, and who are the unfortunate at this time?

When I feel myself becoming irritable, disheartened, or just plain fed-up with life during the pandemic, I find it helpful to conduct a thought-experiment familiar to the ancient Stoics. I reflect on how much I have to be grateful for, and how things could be so much worse. That prompts the more general question: Who are the fortunate, and who are the unfortunate at this time?

Colson Whitehead won his second Pulitzer Prize for The Nickel Boys in 2020, joining the ranks of three other writers recognized for the rare honor. His first was for another historical fiction The Underground Railroad in 2017. What are the odds of winning the Pulitzer for two books that deal with the same subject – the troubled race relations in America? Pretty good, I would say, if your second book is as brilliant as The Nickel Boys.

Colson Whitehead won his second Pulitzer Prize for The Nickel Boys in 2020, joining the ranks of three other writers recognized for the rare honor. His first was for another historical fiction The Underground Railroad in 2017. What are the odds of winning the Pulitzer for two books that deal with the same subject – the troubled race relations in America? Pretty good, I would say, if your second book is as brilliant as The Nickel Boys.

It feels impossible this week not to talk about George Floyd, and yet it feels as if talk has become egregiously cheap, less a mechanism for change than a means of resting in paralyses of complacency, disbelief, or comfort. When rage, grief, frustration, and loss take over communities, states, and entire countries as they have this week, words feel at once like our most important tool and a frantic means of filling what could otherwise be a devastating silence. How do we address a racism so deeply ingrained in society that it feels woven into every fiber of our country’s foundation—and, indeed, was there at the United States’ genesis, when black bodies bolstered a white economy at the expense of their lives, health, and humanity, and in the process built what we so misguidedly call the land of the free, the world’s first great democracy?

It feels impossible this week not to talk about George Floyd, and yet it feels as if talk has become egregiously cheap, less a mechanism for change than a means of resting in paralyses of complacency, disbelief, or comfort. When rage, grief, frustration, and loss take over communities, states, and entire countries as they have this week, words feel at once like our most important tool and a frantic means of filling what could otherwise be a devastating silence. How do we address a racism so deeply ingrained in society that it feels woven into every fiber of our country’s foundation—and, indeed, was there at the United States’ genesis, when black bodies bolstered a white economy at the expense of their lives, health, and humanity, and in the process built what we so misguidedly call the land of the free, the world’s first great democracy?