by Rafaël Newman

I may rise in the morning and notice that a long overdue spring rainfall has revived the flagging vegetation in my kitchen garden. I may give thanks to an unseen, benevolent power for this respite from a protracted and wasting drought. And I may record in my journal: “The heavens cannot horde the juice eternal / The sun draws from the thirsty acres vernal.” In such exercises, I will not have practised rigorous inquiry into the causes of things; I will not have subscribed to any particular view of the metaphysical; and I will certainly not have produced literature. But I will have replicated the conditions for the birth of science, as sketched by Geoffrey Lloyd in his account of the pre-Socratic philosophers, the first thinkers (at least in the Western world) to consider natural phenomena as distinct from the supernatural, however devoutly they may have believed in the latter; and who frequently set down their observations, theories and conclusions in formal language. For my observation of a natural phenomenon (rain and its effect on plant life), while not methodical, would bespeak a willingness to collect and consider empirical data unconstrained by superstitious tradition, and would not necessarily be contradicted by my ensuing prayer of gratitude to a supernatural force; and the verse elaboration of my findings into a speculative theory would not consign them to the realm of poetry (or even doggerel), but would merely represent a formal convention, whose forebears include Hesiod, Xenophanes, Lucretius and Vergil.

I may rise in the morning and notice that a long overdue spring rainfall has revived the flagging vegetation in my kitchen garden. I may give thanks to an unseen, benevolent power for this respite from a protracted and wasting drought. And I may record in my journal: “The heavens cannot horde the juice eternal / The sun draws from the thirsty acres vernal.” In such exercises, I will not have practised rigorous inquiry into the causes of things; I will not have subscribed to any particular view of the metaphysical; and I will certainly not have produced literature. But I will have replicated the conditions for the birth of science, as sketched by Geoffrey Lloyd in his account of the pre-Socratic philosophers, the first thinkers (at least in the Western world) to consider natural phenomena as distinct from the supernatural, however devoutly they may have believed in the latter; and who frequently set down their observations, theories and conclusions in formal language. For my observation of a natural phenomenon (rain and its effect on plant life), while not methodical, would bespeak a willingness to collect and consider empirical data unconstrained by superstitious tradition, and would not necessarily be contradicted by my ensuing prayer of gratitude to a supernatural force; and the verse elaboration of my findings into a speculative theory would not consign them to the realm of poetry (or even doggerel), but would merely represent a formal convention, whose forebears include Hesiod, Xenophanes, Lucretius and Vergil.

Such an accumulation of pursuits may seem bizarre and contradictory to a modern sensibility, which has since relegated each to a separate sphere: the scientist studies the natural world; the cleric provides a conduit to the beyond; and the poet records lived experience in elaborate or heightened language. Read more »

Rutger Bregman’s Humankind: A Hopeful History is a clearly written argument if ever there was one. Bregman believes humans are a kind species and that we should arrange society accordingly. The reason why this thesis needs intellectual support at all is not that it is particularly profound or complicated, but that there are so many misunderstandings to be cleared away, so many apparent objections that need to be overcome.

Rutger Bregman’s Humankind: A Hopeful History is a clearly written argument if ever there was one. Bregman believes humans are a kind species and that we should arrange society accordingly. The reason why this thesis needs intellectual support at all is not that it is particularly profound or complicated, but that there are so many misunderstandings to be cleared away, so many apparent objections that need to be overcome.

Anguilla is a sandbar ten miles long. It’s three miles wide if you’re being generous, but generous isn’t a word that pairs well with the endowments of a small, arid skerry of sand pocked with salt ponds.

Anguilla is a sandbar ten miles long. It’s three miles wide if you’re being generous, but generous isn’t a word that pairs well with the endowments of a small, arid skerry of sand pocked with salt ponds.

Physics writing, let’s face it, is usually pretty boring. In a recent

Physics writing, let’s face it, is usually pretty boring. In a recent

I have a friend who is a self-described “cop magnet.” He’s been arrested six or seven times, just standing there.

I have a friend who is a self-described “cop magnet.” He’s been arrested six or seven times, just standing there.

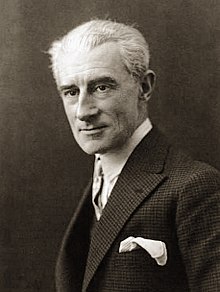

Lately I’ve been craving the music of French composer Maurice Ravel (1875-1937). As reality continues to be fraught, in the midst of a pandemic, social unrest, culture wars, and on and on, Ravel’s music offers an enticing escape. Described by his close friend, concert pianist Ricardo Viñes, as “inclined by temperament toward the poetic and fanciful,” Ravel created music that continues to captivate with its otherworldly beauty. Another reason for his appeal now, when the public health crisis has disrupted all of our quotidian rhythms, is that rhythm is the sine qua non of Ravel’s art. All you have to do is listen to

Lately I’ve been craving the music of French composer Maurice Ravel (1875-1937). As reality continues to be fraught, in the midst of a pandemic, social unrest, culture wars, and on and on, Ravel’s music offers an enticing escape. Described by his close friend, concert pianist Ricardo Viñes, as “inclined by temperament toward the poetic and fanciful,” Ravel created music that continues to captivate with its otherworldly beauty. Another reason for his appeal now, when the public health crisis has disrupted all of our quotidian rhythms, is that rhythm is the sine qua non of Ravel’s art. All you have to do is listen to

Being Korean is a behavioral science all its own. There are formalities at all levels of society and potential affronts lurking in every social engagement. Ageism is set in stone, and in honorifics that define older or younger persons, friends, siblings and relatives, as well as differing levels of social standing. Personal humiliations are many and varied, some of them universally recognizable, some of them exclusive to Korea’s tight-knit family structures or evident hierarchies. It goes beyond how to address someone: How to drink soju, how to pour it for a superior, how to bow, when to bow, who to bow to, when to get down on your knees—the list goes on.

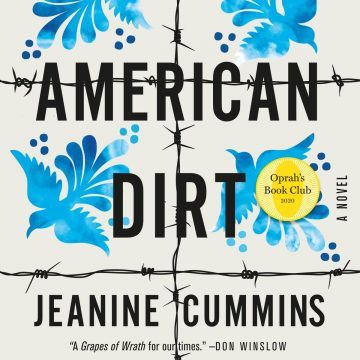

Being Korean is a behavioral science all its own. There are formalities at all levels of society and potential affronts lurking in every social engagement. Ageism is set in stone, and in honorifics that define older or younger persons, friends, siblings and relatives, as well as differing levels of social standing. Personal humiliations are many and varied, some of them universally recognizable, some of them exclusive to Korea’s tight-knit family structures or evident hierarchies. It goes beyond how to address someone: How to drink soju, how to pour it for a superior, how to bow, when to bow, who to bow to, when to get down on your knees—the list goes on. Jeanine Cummins’ American Dirt is a string pulled so tightly it is on the verge, always, of snapping. It is like this from the first sentence, when our protagonist Lydia Quixano Alvarez’s 8-year-old son, Luca, finds himself in a rain of bullets while he uses the bathroom. By the second page, sixteen members of Lydia and Luca’s family are dead, murdered by the reigning drug cartel of Acapulco, Mexico.

Jeanine Cummins’ American Dirt is a string pulled so tightly it is on the verge, always, of snapping. It is like this from the first sentence, when our protagonist Lydia Quixano Alvarez’s 8-year-old son, Luca, finds himself in a rain of bullets while he uses the bathroom. By the second page, sixteen members of Lydia and Luca’s family are dead, murdered by the reigning drug cartel of Acapulco, Mexico.