by Eric J. Weiner

If it looks like a duck, swims like a duck, and quacks like a duck,

then it’s probably a duck.

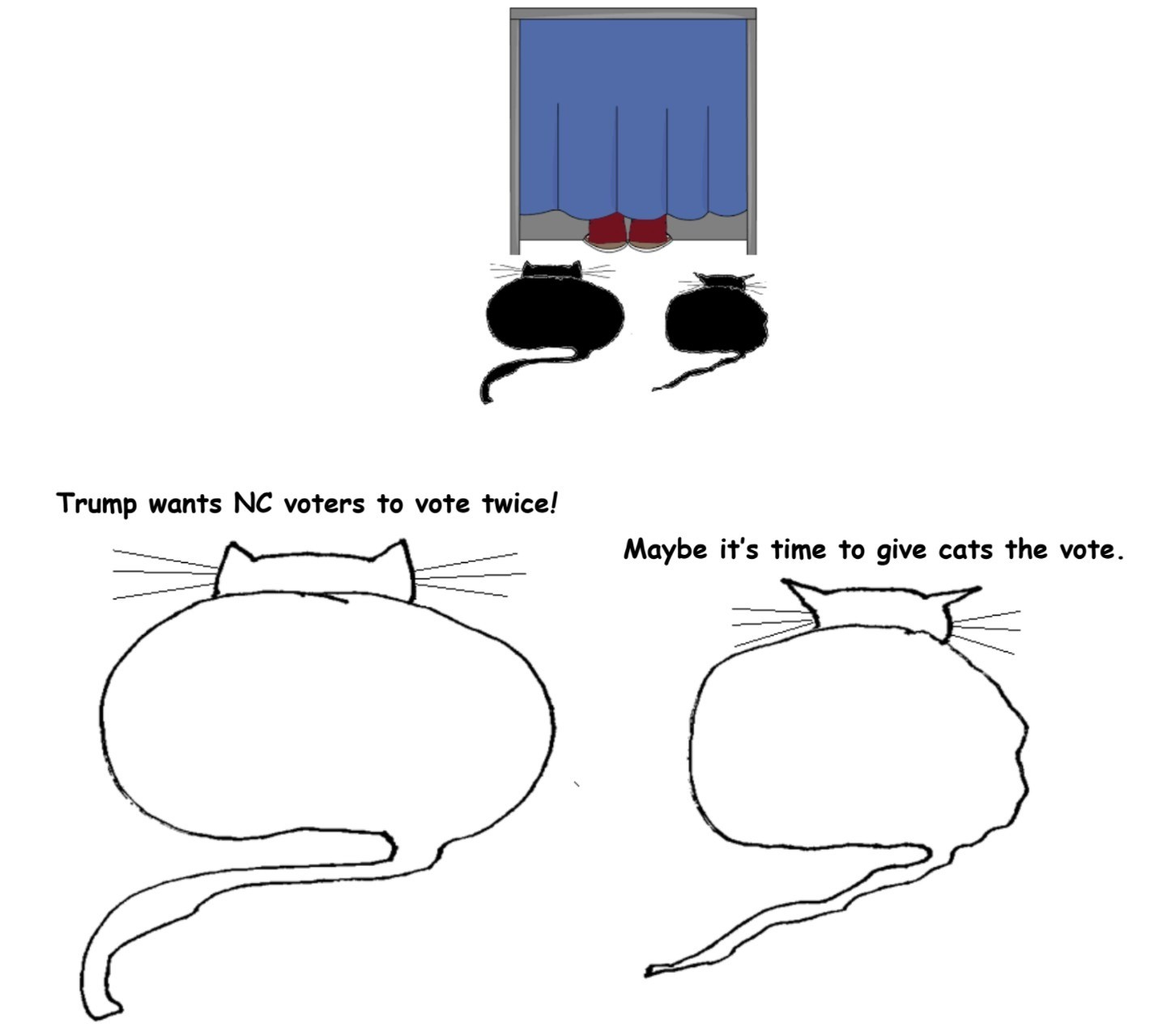

Over the course of two days in early September, the Trump administration quietly formalized its commitment to the ideology of white supremacy within the context of schooling and public education. In two separate but parallel moves, both of which would have made Senator Joe McCarthy proud, Trump announced that the Department of Education (DOE) would investigate public schools to determine if they were using the Pulitzer-Prize winning curriculum, The New York Times’ “1619 Project” while also decreeing that federal employees would no longer receive professional development education about white privilege from the perspective of Critical Race Theory (CRT).[1] If the DOE discovers that schools are using the 1619 Project, Trump has promised, regardless of whether he has the authority to do so, to defund those schools. In spite of the enormous support the 1619 Project has received from educators, intellectuals, and many (but not all) historians, Trump has declared the curriculum “un-American” and a form of anti-American propaganda.[2] The 1619 Project’s goal “to reframe American history by considering what it would mean to regard 1619 as our nation’s birth year [thereby placing] the consequences of slavery and the contributions of black Americans at the very center of the story we tell ourselves about who we are as a country” could only be considered “un-American” by those refusing to acknowledge the historical record: The culture and ideology of white supremacy was foundational and fundamental to the Nation’s birth and history. There is nothing more American than the ideology of white supremacy and Trump’s attempt to declare the 1619 Project “un-American” shows that it is not going away without a fight. With Trump as white supremacist cheerleader, America’s historic connection to the culture and ideology of white supremacy is front and center for the world to see. Read more »

Over the course of two days in early September, the Trump administration quietly formalized its commitment to the ideology of white supremacy within the context of schooling and public education. In two separate but parallel moves, both of which would have made Senator Joe McCarthy proud, Trump announced that the Department of Education (DOE) would investigate public schools to determine if they were using the Pulitzer-Prize winning curriculum, The New York Times’ “1619 Project” while also decreeing that federal employees would no longer receive professional development education about white privilege from the perspective of Critical Race Theory (CRT).[1] If the DOE discovers that schools are using the 1619 Project, Trump has promised, regardless of whether he has the authority to do so, to defund those schools. In spite of the enormous support the 1619 Project has received from educators, intellectuals, and many (but not all) historians, Trump has declared the curriculum “un-American” and a form of anti-American propaganda.[2] The 1619 Project’s goal “to reframe American history by considering what it would mean to regard 1619 as our nation’s birth year [thereby placing] the consequences of slavery and the contributions of black Americans at the very center of the story we tell ourselves about who we are as a country” could only be considered “un-American” by those refusing to acknowledge the historical record: The culture and ideology of white supremacy was foundational and fundamental to the Nation’s birth and history. There is nothing more American than the ideology of white supremacy and Trump’s attempt to declare the 1619 Project “un-American” shows that it is not going away without a fight. With Trump as white supremacist cheerleader, America’s historic connection to the culture and ideology of white supremacy is front and center for the world to see. Read more »

I’ve telecommuted from home for many years now. Before COVID-19, I would rarely turn my camera on when I was on video chats. And if I did, I’d make sure to put makeup on and look somewhat professional and put together from at least the waist up. But since lockdown started in March, I now turn my camera on for almost every video call and I don’t bother to put makeup on or to change my clothes from whatever ratty t-shirt I happen to be wearing. And I don’t care. I sit in my armchair au natural, secure in the knowledge that everyone I’m on calls with is likely dressed casually and taking the call from some room in their home. We’ve seen each other badly in need of haircuts. Then, in some cases, with bad haircuts that we did ourselves or let family members do to us. And we’ve grown familiar with each other’s living spaces, pets, and sometimes family members. I know the view outside of one colleague’s window, the clock on the wall behind another and I always admire the piece of art behind my colleague in Austin. Except for the occasional vacation house rental for a week or two, we’ve all been working out of our homes, living a more lockdown, limited version of the work-life we lived before. It made sense to stay put while lockdown was at its peak. But as it eases up, at least in some places, and while its clear that office life isn’t going back to normal anytime soon, is there a different, new way to live and work?

I’ve telecommuted from home for many years now. Before COVID-19, I would rarely turn my camera on when I was on video chats. And if I did, I’d make sure to put makeup on and look somewhat professional and put together from at least the waist up. But since lockdown started in March, I now turn my camera on for almost every video call and I don’t bother to put makeup on or to change my clothes from whatever ratty t-shirt I happen to be wearing. And I don’t care. I sit in my armchair au natural, secure in the knowledge that everyone I’m on calls with is likely dressed casually and taking the call from some room in their home. We’ve seen each other badly in need of haircuts. Then, in some cases, with bad haircuts that we did ourselves or let family members do to us. And we’ve grown familiar with each other’s living spaces, pets, and sometimes family members. I know the view outside of one colleague’s window, the clock on the wall behind another and I always admire the piece of art behind my colleague in Austin. Except for the occasional vacation house rental for a week or two, we’ve all been working out of our homes, living a more lockdown, limited version of the work-life we lived before. It made sense to stay put while lockdown was at its peak. But as it eases up, at least in some places, and while its clear that office life isn’t going back to normal anytime soon, is there a different, new way to live and work?

We are not dead yet. Battered a little, yes. Frustrated, anxious, wondering about our jobs, our neighborhoods, our schools, absolutely. Definitely not dead.

We are not dead yet. Battered a little, yes. Frustrated, anxious, wondering about our jobs, our neighborhoods, our schools, absolutely. Definitely not dead.

Harold Newton. Untitled, 1960s.

Harold Newton. Untitled, 1960s.

researchers, as well. Indeed,

researchers, as well. Indeed,

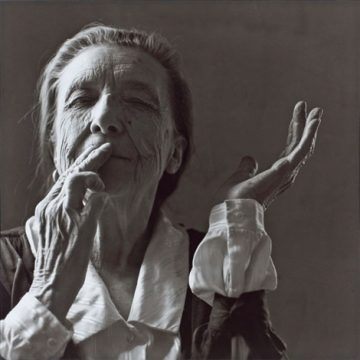

Louise Bourgeois

Louise Bourgeois