by Eric J. Weiner

The delicate balance of mentoring someone is not creating them in your own image, but giving them the opportunity to create themselves. — Steven Spielberg

All mentors teach, but not all teachers become mentors. Mentors nurture, guide, teach, support, protect, challenge, help, listen, defend, critique, and unselfishly share their knowledge, time, and skills with their protégés. The mentor is father, mother, friend, platonic lover, healer, advisor, advocate, confidant, translator, and intellectual broker. The mentor/protégé relationship is not equal nor does it trouble itself with questions of equity. But it is consensual in that the mentor and protégé must both want and agree to the normative demands of the relationship. This does not mean the protégé might not resist, question or challenge his/her mentor. On the contrary, conflict between a mentor and protégé is normal and necessary. But instead of walking away from the relationship because of the tensions and conflicts that might arise, the mentor and protégé work them out, lean into them and, as a consequence, become stronger and more deeply connected. The one hold that is barred from the mentor/protégé relationship is disrespect.[i] Without mutual respect the relationship cannot function as it should and will dissolve, often bitterly.

I have been fortunate to have several mentors throughout my life that have taken me under their care, generously shared their knowledge and time, courageously challenged me when I was wrongheaded, and opened themselves up to my endless inquiries. They showed considerable patience in the face of my tenacious ignorance, insecurity/arrogance, quickness to rage, and tendency toward theoretical abstraction, paralyzing hypocrisy, and self-righteous indignation. My mentors, in different ways, deeply affected who I am today, although I take full responsibility for the tragic flaws and continuing struggles with the aforementioned dispositions of character that still burden me and those closest to me. In the spirit of auld lang syne and from the tradition of Hip-Hop–to look back to pay it forward–I want to give a shout-out to each of my mentors, some of whom I still depend on to set me straight if/when I inevitably go off the rails: (in alphabetical order) Elizabeth “Libby” Fay, Henry Giroux, Jaime Grinberg, Donaldo Macedo, Cindy Onore, and Pat Shannon. Read more »

Adlai Stevenson, in the concession speech he gave after being thoroughly routed by Ike in the 1952 Election, referenced a possibly apocryphal quote by Abraham Lincoln: “He felt like a little boy who had stubbed his toe in the dark. He said that he was too old to cry, but it hurt too much to laugh.”

Adlai Stevenson, in the concession speech he gave after being thoroughly routed by Ike in the 1952 Election, referenced a possibly apocryphal quote by Abraham Lincoln: “He felt like a little boy who had stubbed his toe in the dark. He said that he was too old to cry, but it hurt too much to laugh.”

It’s Monday, 1:45, and six men and I sit in a circle with our German-trained psychotherapist, an imperious woman who reminds us that she is here to help only if we get bogged down or offer guidance and that we men need to find our own way through our turmoil, which is the point of the group and the point of each of us paying $3000 per year. I’m fairly new, so before I speak, I’m seeking some level of comfort or commonality among us, and every week I come up short. I’m not yet adjusted and unsure what I should be adjusting to.

It’s Monday, 1:45, and six men and I sit in a circle with our German-trained psychotherapist, an imperious woman who reminds us that she is here to help only if we get bogged down or offer guidance and that we men need to find our own way through our turmoil, which is the point of the group and the point of each of us paying $3000 per year. I’m fairly new, so before I speak, I’m seeking some level of comfort or commonality among us, and every week I come up short. I’m not yet adjusted and unsure what I should be adjusting to.

We are entering the aftermath. Two of the most epic and wrenching struggles in American history are finally playing out to their conclusions. At last we see a conclusive democratic rejection of a presidency built on systematic lying and racism. At the same time we look just weeks or months ahead for vaccines that will liberate us from our deadly yearlong pandemic.

We are entering the aftermath. Two of the most epic and wrenching struggles in American history are finally playing out to their conclusions. At last we see a conclusive democratic rejection of a presidency built on systematic lying and racism. At the same time we look just weeks or months ahead for vaccines that will liberate us from our deadly yearlong pandemic. A Task for the Left

A Task for the Left

The first time I ever left home without leaving home I was twelve years old, recently back from a winter trip to Mexico. Routinely sent to bed at 8 pm (my parents were old and old-fashioned), always wondering how to fill the inevitable two hours of insomnia, I opted to return to Mexico, not as the sleepless chiquita that I was, but as the fierce guerilla chief I would become in the narrative, leading a band of outlaw Aztecs in raids against a host of injustices from base camp in a desert. No precedents existed for my leadership skills in real life, but within the carefully sculpted storyline of the daydream, I was both charismatic and respected, not merely proficient but also inspired, a warrior queen to rival any Amazon.

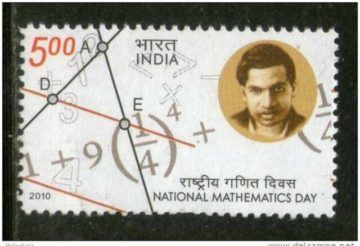

The first time I ever left home without leaving home I was twelve years old, recently back from a winter trip to Mexico. Routinely sent to bed at 8 pm (my parents were old and old-fashioned), always wondering how to fill the inevitable two hours of insomnia, I opted to return to Mexico, not as the sleepless chiquita that I was, but as the fierce guerilla chief I would become in the narrative, leading a band of outlaw Aztecs in raids against a host of injustices from base camp in a desert. No precedents existed for my leadership skills in real life, but within the carefully sculpted storyline of the daydream, I was both charismatic and respected, not merely proficient but also inspired, a warrior queen to rival any Amazon. In the summer of 2000, after completing my bachelor’s degree in engineering, I had to decide where to go next. I could either take up a job offer at a motorcycle manufacturing plant in south India, or I could, like many of my college friends, head to a university in the United States. Most of my friends had assistantships and tuition waivers. I had been admitted to a couple of state universities but did not have any financial support. Out a feeling that if I stayed back in India, I’d be ‘left behind’ – whatever that meant: it was only a trick of the mind, left unexamined – I took a risk, and decided to try graduate school at Arizona State University. I hoped that funding would work out somehow.

In the summer of 2000, after completing my bachelor’s degree in engineering, I had to decide where to go next. I could either take up a job offer at a motorcycle manufacturing plant in south India, or I could, like many of my college friends, head to a university in the United States. Most of my friends had assistantships and tuition waivers. I had been admitted to a couple of state universities but did not have any financial support. Out a feeling that if I stayed back in India, I’d be ‘left behind’ – whatever that meant: it was only a trick of the mind, left unexamined – I took a risk, and decided to try graduate school at Arizona State University. I hoped that funding would work out somehow. One of the most interesting and memorable characters in sci-fi films is the

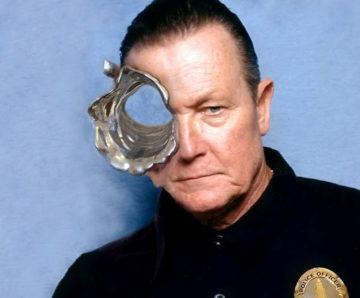

One of the most interesting and memorable characters in sci-fi films is the