by Chris Horner

A Task for the Left

A Task for the Left

‘Freedom’ must be about the most popular term in the world of politics, and not only in that world. But what does it actually mean, in social and political terms? How should people who want to be broadly progressive understand it? Too often the Left finds it hard to articulate just how they stand in relation to it and the effect is to cede the term to the Right. This is important, as the word, vague as it is, carries enormous affective force. It matters to people, because it represents a vital human aspiration. And so it’s too important to be abandoned to the people who are, for all their rhetoric, actually the enemies of freedom. On their account of it, freedom is just about individuals having more choices. This is a very weak account of freedom that ought to be met head on and refuted. It won’t do to change the subject, or talk vaguely about equality and solidarity: the Left needs make it clear what freedom is, what it isn’t, and what it could be. If it doesn’t, it risks being portrayed as being ‘against’ freedom, and in favour of mediocre uniformity and regimentation. So we end up with two caricatures, one about freedom and the other about its supposed enemies.

2020 had plenty of examples of this weak version of ‘freedom’. The Covid pandemic led to masks being rejected, vaccines shunned and lockdowns attacked and breached, all in the name of individuals’ rights and freedoms and ‘freedom of choice’. Beyond Covid, in the UK the freedom flag has been waved in support of Brexit, which apparently also means freedom, via the sloughing off of regulations. In the UK and US the word is hardly ever out of the mouths of Prime Ministers and Presidents. Hardy perennials of the right continue to be diatribes against against Health and Safety at work (‘red tape’), tax (the freedom to spend the money one earns as one pleases) and of course, in favour of arrangements that allow ‘flexible working’ – supposedly to free up the choices of employer and employee, but which in fact confirm the precarious status of hundreds of thousands of workers. Then there are ‘free schools’, free markets and much more. It’s an extremely long list. The Left is generally cast as the enemy of all this, the enemy of aspiration, of social mobility, of the opportunity to become a billionaire. It just wants equality, which stifles freedom.

How should one respond to this?

Certainly not by trying to change the subject to some other desirable social goal, like equality, or community. Sure, these are important things to argue for, but the challenge ought to be to show what is wrong with this freedom argument, and to show that it is a false bill of goods, a promise that vanishes like scotch mist when one actually tries to grasp it. Too many on the left cede this ground, assuming the social good of, say, equality, must eat into that of freedom, as if the alternative was between freedom or equality. But this is quite wrong. What we need isn’t a retreat on the freedom issue as it is presented by conservatives, ‘centrists’, libertarians and others but a better account of what freedom actually is: control over one’s life.

Neoliberal freedom

Something else lies behind the noise that is made about freedom of choice. That something is a particularly twisted notion of the relation of the individual to society that we have had promoted at us in recent decades. It is a neoliberal account, based on the idea that the individual should self identify as an ‘entrepreneur of the self’. More than an idea, it is an attempt to mould a new kind of person, a subject-consumer understood in cost/benefit terms, who only thinks in terms of self and (maybe) her family. On this model of the self, only the  individual and her self chosen commitments matter. Freedom is freedom of choice, nothing more, and the more one has of it, the freer one is. The state can only get in the way here and should be limited to policing cases of clear harm to others arising from the unwise or malicious use of individual freedom. However, the language of choices, limited by what is sometimes called the ‘harm principle’, tends only to be really useful in situations where an individual is at risk of harm, or may to cause harm to others. It is harder to apply it to, say, the employer trying to worm his way out of financial responsibilities to his workers by claiming that they are self employed, while actually treating them as his employees in every other respect.

individual and her self chosen commitments matter. Freedom is freedom of choice, nothing more, and the more one has of it, the freer one is. The state can only get in the way here and should be limited to policing cases of clear harm to others arising from the unwise or malicious use of individual freedom. However, the language of choices, limited by what is sometimes called the ‘harm principle’, tends only to be really useful in situations where an individual is at risk of harm, or may to cause harm to others. It is harder to apply it to, say, the employer trying to worm his way out of financial responsibilities to his workers by claiming that they are self employed, while actually treating them as his employees in every other respect.

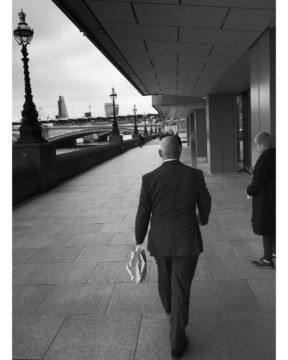

The neoliberal view of the individual and her freedom is bogus, and the proponents of it are often insincere, outside of a hard core of ‘libertarian’ fanatics. It is a ‘choice agenda’ that collapses in the face of the deep inequalities of power in today’s society, which is why it never delivers on its promises. The individual, freed from the ‘nanny state’, is dwarfed by the power of the Corporation, the Employer, and ultimately Capital.

Freedom as Control

The Left should reframe the freedom question as one that concerns the degree of real control people have over key aspects of their lives: things like work (or the lack of it), basic services, democracy and more. In each case we should ask: does this increase the amount of control a person has over their life? Instead of the view that freedom is just about making choices, this shifts the emphasis onto the question of how much real autonomy one has. And this immediately opens up wider issues.

Work

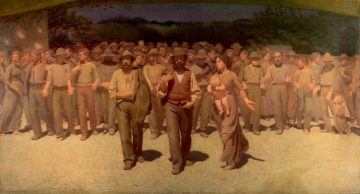

Think of the world of work, and that of non work. Too many of us work too many hours of our lives in jobs that are either unrewarding, badly paid or unnecessary – and sometimes all three. Freedom, here, is the right to sell one’s labour power in order to get the means to live, if we are lucky to have a job that pays in the first place. If we are not lucky we may subsist on a punitive benefits system designed to humiliate and break the spirit. What kind of freedom is this? And many more do the kinds of work that the market doesn’t see as ‘value producing’: think, for instance of the hours of unpaid labour people, mainly women, do in caring for the sick and the elderly. If we work long hours, if we are exhausted by our labour, whether ‘productive’ or not in market terms, if we are deprived of the resources to do more than stay alive, we are not free, and we are not living as fully as we might. If automation is going to transform the world of work, then we should make sure that it begins to change all that for the better. People need less time at work and more resources and opportunities to enjoy their free time. For life could be something with more in it than hard labour and the struggle to keep one’s head above water. Something in which can find out what kind of things they can do, or want to do, a thing where they can grow and learn, play and discover. A thing to enjoy and not just endure.

Basic Services

Basic Services

Freedom, if it is to be real, implies a certain kind of social arrangement. It won’t do to roll the state back and leave the individual to his or her devices, sink or swim. If I want the freedom to be educated, then it follows that there should be a properly funded education system; if I want to be free of illness so I can get on with my life, I need a health system, and so on. If such things are left to the market, they will tend to enrich and assist the few, while loading the rest with debt. All this implies a social dimension, not just an individual one. It means a tax system that can fund such things, and it means that my freedom will be dependent on the work and will of many others. None of this is glamorous, but it is vital, and it touches peoples’ lives in a very real way.

Some important facts have stared us in the face in 2020. It is that the picture of the society as a mass of independent individuals bouncing around like ping pong balls is fatuous. All of us are connected in multiple, uncountable ways to others. Family, yes, but also neighbourhood, fellow workers and so on. Beyond them, we rely on the others unknown to us who provide the services that are the basis for our lives: water and power, transport and so on. I need these to work well so I don’t have to think about them, so I can get on with doing what I want to do. What I don’t need are more false ‘choices’ between water, rail or internet companies – which often turn out to be de facto monopolies in any case. I depend on the multitudes of others who work to keep me healthy and safe -the many who labour, who produce the value that that keeps the economy functioning, who transport things to my door, who get me to the hospital, who put out the fires. Society is a complex network that enables rather than constrains. My freedom depends on it.

The Consumer

The Consumer

Choice certainly has its place, when we go shopping for instance, although it has its limits even there. How many kinds of toothbrush to choose from do I really need to be happy? More complex buying decisions that the ‘entrepreneur of the self’ is supposed to make for herself can be fraught with danger. The single person trying to find a way through the complexities of investments, pensions, insurance and so on, can be gulled out of their savings or just make unwise decisions that cost them dear. The free market isn’t free for most people, as there is no equal distribution of knowledge, and power manifests itself through inequality of access to information. Not many of us have the time or expertise to master the complexities of the world of financial services. Even in a world in which everyone acted honestly, lack of knowledge would mean vulnerability for the ordinary person. And not everyone is honest. At the very least, proper oversight and regulation is essential for the welfare of the many; in many cases the return of a major role for the state or other non profit agencies would be welcome. For truly, freedom for the pike is death to the minnows.

Democracy

There is a real democratic deficit in almost all areas of our lives, and in most of the institutions we come in contact with. Many places of work, for instance, are run in a hierarchical manner reminiscent of feudalism, combined with a level of surveillance unknown to our peasant ancestors. And in local government we often find that the supposed organs of local democracy are more responsive to the rich and powerful than they are to those whom they are supposed to represent. Where I live developers are getting a free pass to gentrify the neighbourhood, regardless of the wishes of the people who live there, and which will have the effect of pricing out local people. This was after a show of ‘consultation’ by the local authority that was really a formality, since the development was foregone conclusion. Powerlessness and lack of effective local democracy is a denial of freedom. We must make that case, loudly and repeatedly.

Society is composed of more than lots of individuals. It is characterised by the presence of larger structures than the lonely self: institutions. We are formed by them and must contend with them in one way or another: families, schools, the media, the workplace, etc. It is quite misleading to imagine one can do without them, or that their only role is to limit our freedom. They can limit or crush freedom, of course – or they can act as the means by which it is nurtured and preserved. The key thing is how we fashion them, together, with the goal of enhancing everyone’s freedom. Democratising institutions is an essential part of ensuring people have a measure of control over what happens to them and their communities.

Arguing for freedom

Arguing for freedom

The Left needs to make the argument that we are indeed ‘all in this together’ but that the institutions of a predatory capitalism – the same capitalism that prates about the freedom of the market – are the enemies of any real freedom. If you are worked to exhaustion, deprived of the financial means to live a decent life, confronted with insecure or non existing housing and precarious jobs, if the very environment is poisoned, if the place you live in is the prey to developers, then you aren’t genuinely free.

How can the political left make all this concrete? It can seem a daunting task. I wouldn’t advise any political activist to try to launch a discussion about social ontology on the doorstep. Yet people are not unaware of the current way ‘freedom’ is used as bait and switch, nor are they unaware of what they owe to the efforts of others. People tend to respond, in my experience, less to general arguments and more to specific issues. Sometimes it is a matter of right time and place, and about quite unglamorous things, like a free high speed broadband, a better funded and more effective health service, an affordable and effectively integrated transport system. And then there is the challenge of automation. Instead of seeing the decreasing need for living labour in the economy as a threat, we could see it as an opportunity to transition to a shorter working week. The case of that should be made now.

Genuine freedom is linked to the ability to have real control over how I live my life, and the market solution of freedom as choice simply cannot meet that need. Only collective action and a recognition that we are part of something bigger than our selves can begin to do this. Another word for this is ‘socialism’: we should go out and argue for it.