by Brooks Riley

The first time I ever left home without leaving home I was twelve years old, recently back from a winter trip to Mexico. Routinely sent to bed at 8 pm (my parents were old and old-fashioned), always wondering how to fill the inevitable two hours of insomnia, I opted to return to Mexico, not as the sleepless chiquita that I was, but as the fierce guerilla chief I would become in the narrative, leading a band of outlaw Aztecs in raids against a host of injustices from base camp in a desert. No precedents existed for my leadership skills in real life, but within the carefully sculpted storyline of the daydream, I was both charismatic and respected, not merely proficient but also inspired, a warrior queen to rival any Amazon.

The first time I ever left home without leaving home I was twelve years old, recently back from a winter trip to Mexico. Routinely sent to bed at 8 pm (my parents were old and old-fashioned), always wondering how to fill the inevitable two hours of insomnia, I opted to return to Mexico, not as the sleepless chiquita that I was, but as the fierce guerilla chief I would become in the narrative, leading a band of outlaw Aztecs in raids against a host of injustices from base camp in a desert. No precedents existed for my leadership skills in real life, but within the carefully sculpted storyline of the daydream, I was both charismatic and respected, not merely proficient but also inspired, a warrior queen to rival any Amazon.

Where did this come from, this semi-androgenous role so foreign to my timid female self? I may have been feeling powerless back then, on the verge of puberty and alone in my ignorance. My daydream could just as easily have come from a twelve-year-old boy but more likely it incubated in the tomboy I sometimes was. Gender had little to do with it, though. Empowerment is what mattered, something I desperately needed, as well as a jolly exciting way to pass the time until I fell asleep.

Daydreams have served the needs of human beings since the evolution of the imagination a few million years ago. The caveman who dreamed of bagging a boar pictured an encounter in his mind and practiced his moves. Except for those with aphantasia, we can all visualize places we’ve been and people we’ve seen. This ‘inner eye’ allows us to do much more than that—to create people and places that we’ve never seen, that don’t exist, and to give them life, context, and raisons d’être. This is how fiction is born, before the first word has even hit the page.

We all indulge in daydreams, those reticules in the mind that hold our most vivid hopes in the form of mise-en-scène, endowing our bucket list with emotional nuance and narrative—however improbable the reality. With age, however, imagining a dazzling future no longer seems viable, as the scope of our hopes and desires shrink, like the law of diminishing returns. Daydreaming is eventually reduced to hardly more than an imagined walk in the park when you’re stuck at home. Much of my bucket list has been accomplished, in sometimes surprising ways. My life has been eclectic, peripatetic, unexpected, and gratifying. I’ve been places, done things. What more could there be to dream about?

Then along came the pandemic, adding personal peril to the suffocating, four-year omnipresence of Donald Trump, itself a form of detention. In spite of the cornucopia of available digital entertainment, I found myself resurrecting the old childhood habit, flexing the muscles of my imagination and launching into an imagined series of events. Now is a time when daydreams serve a therapeutic role, as crucial escape mechanisms for those who are locked down, locked up or locked into a toxic GIF that keeps on giving. Daydreaming is no longer a luxurious diversion but a psychological necessity, an imaginary social contract with what’s left of the world. Just as daydreams maintain sanity for those in solitary confinement, they also have the potential to provide an alternative universe where it’s safe to roam around without a mask, for instance, or hug a friend. But such an environment may require constant maintenance for it to enrich the long days and nights of reduced mobility and isolation. It’s worth the effort.

The burgeoning syllabus of pandemic lockdown pastimes now includes a genre on pretending. The New York Times publishes a whole travel series called ‘How to pretend you’re in [insert a city] tonight’, offering tips for feeling just a bit closer to somewhere you’re not, especially since you can’t actually go there right now. Movies, music, language and recipes are suggested to flesh out the pretense. This idea is fine as far as it goes. But where’s the story?

The daydream is a novel with a readership of one. Published fiction could be described as other people’s daydreams and for avid readers a more satisfying diversion than inventing one’s own scenario. But there’s a lot to be said for tailoring a story to one’s idiosyncrasies and following through without having to hold to someone else’s tempo or descriptive choices.

This time around, my Mexico became South Korea, a land I knew little about until I saw the series Mr. Sunshine a year ago. Like Mexico, South Korea is not without its dark side, its social problems. But from afar, it seemed the perfect antidote to the misery at home: the expressive language, the formalities, the modesty, the talent, the humor, the outrageous feats of storytelling, the warm social rituals, the gestures, the refreshing silliness, the love of aphorisms. After binging on a few more Hallyu highlights, I was unable to watch fare from the West anymore.

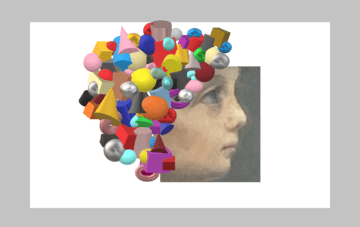

In daydreams, verisimilitude hardly matters. Although I could remember the smell of the desert and feel the hot, dusty air in my childhood fantasies of Mexico, I might have been mistaken about tiny details. With Korea, it’s different. I’ve never been there. My Seoul is a collage of impressions gleaned from films, TV series, documentaries, and daily reads of the Korea Times or Korea Herald. I’ve imagined the taste of kimchi, but my memory from the one time I ate it long ago could be all wrong. For the purposes of the world I’ve created, that doesn’t matter. I’ve attached a taste to kimchi that is probably close to the truth. The same goes for Jajangmyeon, the ubiquitous noodles with black bean sauce that get slurped up in nearly every Korean series I’ve seen. I can imagine what pork belly smells like on the grills at each restaurant table.

But what about the stories? The stories unfold like movies in the mind, some set in the present, and one in the early Joseon period. Forging my way through the plots is a nightly ritual before sleep, a mental activity that overrides worry and anxiety. I wander through the city to soak up the details. I design the sets, find locations and write dialogue. I choose the cast and play a role too, but not one that reflects my actual age or origin. In most of these daydreams I am Korean and ageless, effectively fictionalizing my entire being for the purposes of escape. Korea looks like home to me, the faces familiar and reassuring. I am in total immersion.

Will I go to Korea when the pandemic ends? I hope so, even if the chances are slim, even if the Korea of my dreams doesn’t exist. But for now, without leaving home, I want to fully function somewhere other than where I am in time and space, somewhere once upon a time, far, far away.