by Andrea Scrima

Adapted from a talk given on April 28, 2017 at the New School, New York City, as part of The Body Artist: A Conference on Don DeLillo.

For some readers, Don DeLillo is a guy thing: an immensely gifted geek whose male characters are incapable of emotional communication; whose dialogue sounds more like the brilliant inner monologues of a mind challenging its own assumptions than individual expressions of distinct personalities; who has examined, analyzed, and celebrated American culture with a wistful nostalgia for baseball, poker, fistfights, and billiards, the kind of rough-and-tumble male bonding that redeems unremarkable domestic existence. Whatever his weaknesses might be, most would agree that DeLillo is a wary paranoiac with an uncanny ability to predict, well in advance, shifts in culture, technology, and the communication media and their effects on individual and collective psychology and to express these phenomena in evocative and hypnotic prose. DeLillo speaks powerfully to American obsessions: our anxiety at being alive, our fear of death, the way in which our efforts to transcend ourselves in some meaningful way are stymied by a culture that both engenders and entraps us. The question now is whether his work can help us analyze the unprecedented political situation we find ourselves in today.

I’ve been living in Berlin for over thirty years. Live outside your native culture long enough, and you begin to see it as a sort of double exposure in which your sense of family and identity and belonging is overlaid with a strange, shape-shifting disturbance pattern in which everything seems normal until it suddenly doesn’t, and you begin to see the country from a foreigner’s point of view. For as long as I can remember, America has enjoyed its superpower status, exporting the products of its creative industries around the globe, often through aggressive means, and showing little sustained interest in the cultures of other countries. Lawrence Venuti, the translation theorist, has spoken of “a trade imbalance with serious cultural ramifications” resulting in “a complacency in Anglo-American relations with cultural others, a complacency that can be described—without too much exaggeration—as imperialistic abroad and xenophobic at home.” Only a tiny percentage of all publications in the United States are works in translation, meaning that we have comparatively meager resources to examine our society and culture in comparison to other societies and cultures, and that this impedes our ability to reflect objectively on ourselves.

What does this have to do with Don DeLillo? Read more »

I think it is fair to say that we usually see science and magic as opposed to one another. In science we make bold hypotheses, subject them to rigorous testing against experience, and tentatively accept whatever survives the testing as true – pending future revisions and challenges, of course. But in magic we just believe what we want to be true, and then we demonstrate irrational exuberance when our beliefs are borne out by experience, and in other cases we explain away the falsifications in one way or another. Science means letting what nature does shape what we believe, while magic means framing our interpretations of experience so that we can keep on believing what feels groovy.

I think it is fair to say that we usually see science and magic as opposed to one another. In science we make bold hypotheses, subject them to rigorous testing against experience, and tentatively accept whatever survives the testing as true – pending future revisions and challenges, of course. But in magic we just believe what we want to be true, and then we demonstrate irrational exuberance when our beliefs are borne out by experience, and in other cases we explain away the falsifications in one way or another. Science means letting what nature does shape what we believe, while magic means framing our interpretations of experience so that we can keep on believing what feels groovy.

Let me recommend a New Year resolution, in case you don’t have one yet: Be nicer to people you disagree with.

Let me recommend a New Year resolution, in case you don’t have one yet: Be nicer to people you disagree with.

The German language is famous for its often long compound words that combine ideas to neatly express in a single word complex notions. Torschlusspanik, (gate-shut-panic), for instance, referred in medieval times to the fear that one was not going to make it back into the city before the gates closed for the night, and now signifies the worry, common among middle aged people, that the opportunities for accomplishing one’s dreams are disappearing for good. Backpfeifengesicht, sometimes translated as “face in need of a fist”, means a face that you feel needs slapping.

The German language is famous for its often long compound words that combine ideas to neatly express in a single word complex notions. Torschlusspanik, (gate-shut-panic), for instance, referred in medieval times to the fear that one was not going to make it back into the city before the gates closed for the night, and now signifies the worry, common among middle aged people, that the opportunities for accomplishing one’s dreams are disappearing for good. Backpfeifengesicht, sometimes translated as “face in need of a fist”, means a face that you feel needs slapping.

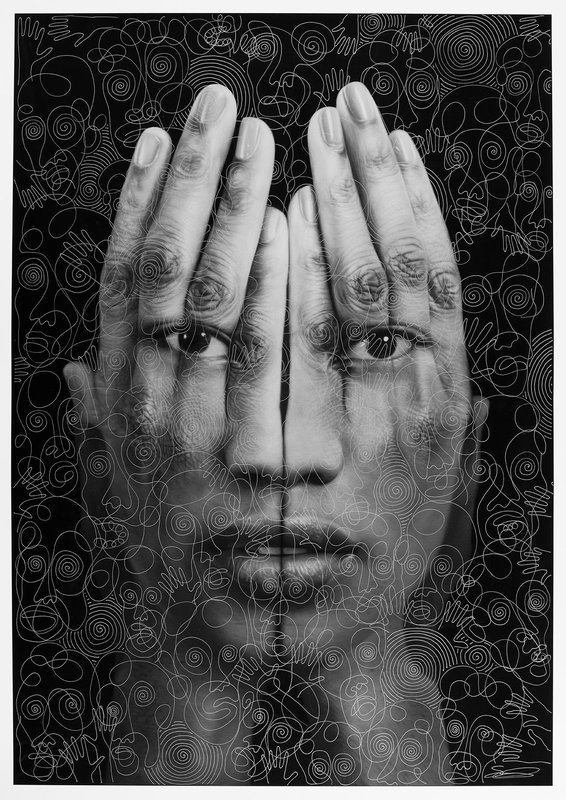

Tigran Tsitoghdzyan. Black Mirror, 2018.

Tigran Tsitoghdzyan. Black Mirror, 2018.