by Carol A Westbrook

It is 42,000 years ago, somewhere in central Europe. A human hunter treks through the forest, dressed in furs. He is carrying a large pack. Alongside him is his mate, a short, blond Neanderthal woman, and their son, about 8 years old, with features of both.

They reach their destination, a Neanderthal dwelling adjacent to the winder cave.

A man walks out, pleased to see his daughter and her mate, along with their son.

“Greetings and welcome, he said.

“Greetings back to you,” the human says. “I have brought some gifts.”

He presents the two saber-tooth tiger pelts and the large teeth to the Neanderthal man. The man reciprocates by giving him some well-crafted flint tools, a spear tip and a scraper.

“Today, I will show my grandson how to chip flint.”The H. sapiens thanks him. He is anxious to bring this expertise to his tribe. The Neanderthal flints were the finest in the area.

His wife goes off to help her mother cook the food. The Neanderthal man said to the homo sapiens man,

“I’m so glad you took my daughter to mate. It is getting hard to find any of my tribe, and few sons of an age to mate. We have grown scarce as a people.”

He replies,”Thank you, old father. Your daughter is a good wife, she is kind and hard-working and will bear me many children.”

For several weeks they shared food, slept in their furs, and the old Neanderthal man taught the boy to chip flint tools. After one moon cycle they left for their own valley, with fond good-byes.

This is a very different portrayal of Neanderthal life from what we previously imagined. Ever since 1859, when the first Neanderthal bones were discovered in a cave of Germany’s Neander Valley, these creatures were thought to be sub-human primates, living in caves like animals, hunted to extinction by our ancestor homo sapiens. Recent scientific and archeologic studies suggest that this was not the case at all; rather, the Neanderthals were humans, too, who lived very much like their homo sapiens counterparts, with speech, fire, stone tools, and artwork! They were human in many respects, and the homo sapiens tribes that met up with them probably regarded them as just another tribe of people, with whom they traded and intermarried.

The DNA record tells us much about this extinct race. The first Neanderthal genome was sequenced in 2013 from a female skeleton in Croatia. The sequence opened up a wealth of information about our distant relatives. Homo neanderthalensis and Homo sapiens were found to be species of the genus homini. A genus is a taxonomic group of related species who share a common ancestor. The DNA record shows that H. sapiens and H neanderthalensis had a common ancestor about 500,000 years ago in Africa. The two races may not have been distinct during this time, but after 100,000 years the groups went their separate ways. Their DNA continued to evolve, as the Neanderthals developed traits such as fair skin, freckles, and red hair, but their basic chromosome structure remained the same. This enabled both species to mate and produce fertile offspring, which was not possible with other primates such as the great apes. Homo sapiens remained in Africa, while Homo neanderthalensis began to settled the Indo-European continent, about 100,000 year ago, before Homo sapiens arrived. Then, about 50 – 60,000 years ago, groups of Homo sapiens began to migrate north, away from their cradle in Africa, when they again encountered Neanderthals, this time in Europe. DNA studies show that the humans and Neanderthals interbred during this time, which is the reasons humans like us have so much Neanderthal DNA in our genome.

Many of the features we attribute to Neanderthal DNA were inherited by humans through interbreeding, and can still be found in modern populations. These include large hands prominent brow ridges, red hair, immunity to some Indo-European pathogens, and tendencies toward Type 2 Diabetes and lupus. In spite of their different appearances, culture and language, it seems that Homo sapiens did not regard Neanderthals as sub-human creatures worthy of extermination, but rather as just another tribe with different culture and language.

It seems very likely that Neanderthals had the capacity for complex speech. A computerized 3-D modeling system was used to examine fossilized hyoid bone, a throat bone that supports the base of the tongue, and allows for complex sounds to be made with the tongue. In other primates, the hyoid bone is elsewhere in the throat and they cannot produce speech sounds. So Neanderthal skull structure suggests that speech and laughter were present in this race. The ability to communicate in complex language, rather than sign language, frees up hands for other activities and further develops the brain capacity to do so.

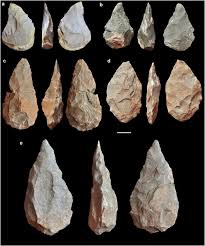

Neanderthals crafted stone tools, such as scrapers, knives, and spear points. These were well-made tools that were as good as those of the homo sapiens, with beauty, balance, and utilitarian design. Furthermore the Neanderthals were able to craft these points into very functional instruments, including throwing spears, something that was initially felt to be done only by Homo sapiens. Throwing spears have significant advantages over stabbing tools; it’s easier to sneak up on an animal and is safer for the hunter, and their vocal language allowed them to communicate and coordinate their attacks from a distance.

In addition to their cave dwellings, Neanderthals built wooden structures. Few of these structures survive from so long ago, but there is one site with wood posts arranged in the shape of a large room outside of a cave. These house posts might have held up roofs, or be covered in skin or bark. They were probably used as summer residences, while in the winter the tribes sheltered in caves, building fires to keep warm, to protect themselves from dangerous animals, and to cook the meat that they hunted.

So we see that Neanderthals were not wild animals, grunting and huddling together in caves. They were humans. They had speech, and showed signs of higher intelligence in their toolmaking, group activities, and shelter building. Did they have dreams and aspirations? Did they have imagination and abstract thought? I believe they did. The most compelling evidence is their artwork, recently discovered deep in caves in France. These paintings were done about 64,000 years ago, long before homo sapiens arrived in Europe, so they could only have been done by the Neanderthals.This video is a tour of the artwork in one of these caves: Neanderthal Cave Art.

The artists used red and black pigments, and depicted groups of animals, hand stencils, and geometric designs. The hand prints are especially compelling.  What do they say to us? “This is me. This is my signature. This is my work.”

What do they say to us? “This is me. This is my signature. This is my work.”

Neanderthals were our cousins. We had the same grandparents at one time in Africa. Then the populations that would give rise to homo sapiens and Neanderthals separated, with Homo sapiens staying in Africa and Homo neanderthalensis migrating to Europe. They were separated for 4,0000 generations, during which time the Neanderthals developed much genetic diversity. Homo sapiens evolved, too, with their face and jaw shape becoming more streamlined and losing the brow ridges. Then the distant cousins met again, in Europe and Indochina. For about 2,500 years they co-existed and intermarried, probably regarding each other as just different tribes, rather than different species. We know we have a genetic legacy of about 1 – 4 % Neanderthal DNA. But what happened to our cousins? Where did they go?

It’s unlikely that humans hunted the Neanderthals to extinction, as was previously thought; none of the encampments showed signs of violent deaths. Instead, there is evidence that the Neanderthals were already dying out, for whatever reason. Their numbers were dwindling, and there was less genetic diversity. Climate change may have been a factor, as the earth was getting colder. Perhaps a pandemic finished them off. We can speculate, but we’ll never know.

The Neanderthal may be gone, but they live on in our genome. Twenty percent of Neanderthal DNA currently survives in modern humans. These genes provided us with additional genetic diversity, ironically as the Neanderthals were losing theirs. So when you get your DNA test results back, and find that you have some Neanderthal DNA, think fondly of your cousins, and long distant grandparent. And wonder what happened to their tribe.