by Ashutosh Jogalekar

I have been thinking a lot about change recently. 2020 seemed like a good year to do this, for several reasons. There was the political turmoil in the United States where I live. There was the global pandemic. There was the birth of our daughter. There were a few projects I worked on related to long term change on evolutionary timescales. All of these issues gave me the opportunity to think about change and some of the paradoxes associated with it. Everybody defines change in their own way, and some changes may be more important to some of us than to others, so how we react to, adapt to and enable change is ultimately very subjective. And yet we all have to deal with some very objective measures of change, at the very least those pertaining to life and death. So the paradox of change is that while it impacts us on a very subjective, personal level and each of us perceives it very differently, on another level it also unites us because of its universal aspects, aspects that can help us define our common humanity.

There was of course the pandemic that forced great changes. A way of life which we took for granted was suddenly and irrevocably changed. Careers and lives ended, we hunkered down in our homes, stopped traveling and started looking inward. For some of us who had been caught up in immediate matters of family, the pandemic even came as a welcome respite in which we got to spend more time with our significant others and children. We stepped back and reevaluated our life on the treadmill. For others, it posed a constant challenge to get work done, especially with kids whose schools were closed. For my wife and me, the pandemic was a chance to spend more time with our newborn daughter and avoid the stresses and boredom of the commute and stresses of physical meetings in the office. What can be unwelcome change for one can be unexpectedly welcome for another. In this particular case we were privileged, but the tables could well be turned. Read more »

I think it is fair to say that we usually see science and magic as opposed to one another. In science we make bold hypotheses, subject them to rigorous testing against experience, and tentatively accept whatever survives the testing as true – pending future revisions and challenges, of course. But in magic we just believe what we want to be true, and then we demonstrate irrational exuberance when our beliefs are borne out by experience, and in other cases we explain away the falsifications in one way or another. Science means letting what nature does shape what we believe, while magic means framing our interpretations of experience so that we can keep on believing what feels groovy.

I think it is fair to say that we usually see science and magic as opposed to one another. In science we make bold hypotheses, subject them to rigorous testing against experience, and tentatively accept whatever survives the testing as true – pending future revisions and challenges, of course. But in magic we just believe what we want to be true, and then we demonstrate irrational exuberance when our beliefs are borne out by experience, and in other cases we explain away the falsifications in one way or another. Science means letting what nature does shape what we believe, while magic means framing our interpretations of experience so that we can keep on believing what feels groovy.

Let me recommend a New Year resolution, in case you don’t have one yet: Be nicer to people you disagree with.

Let me recommend a New Year resolution, in case you don’t have one yet: Be nicer to people you disagree with.

The German language is famous for its often long compound words that combine ideas to neatly express in a single word complex notions. Torschlusspanik, (gate-shut-panic), for instance, referred in medieval times to the fear that one was not going to make it back into the city before the gates closed for the night, and now signifies the worry, common among middle aged people, that the opportunities for accomplishing one’s dreams are disappearing for good. Backpfeifengesicht, sometimes translated as “face in need of a fist”, means a face that you feel needs slapping.

The German language is famous for its often long compound words that combine ideas to neatly express in a single word complex notions. Torschlusspanik, (gate-shut-panic), for instance, referred in medieval times to the fear that one was not going to make it back into the city before the gates closed for the night, and now signifies the worry, common among middle aged people, that the opportunities for accomplishing one’s dreams are disappearing for good. Backpfeifengesicht, sometimes translated as “face in need of a fist”, means a face that you feel needs slapping.

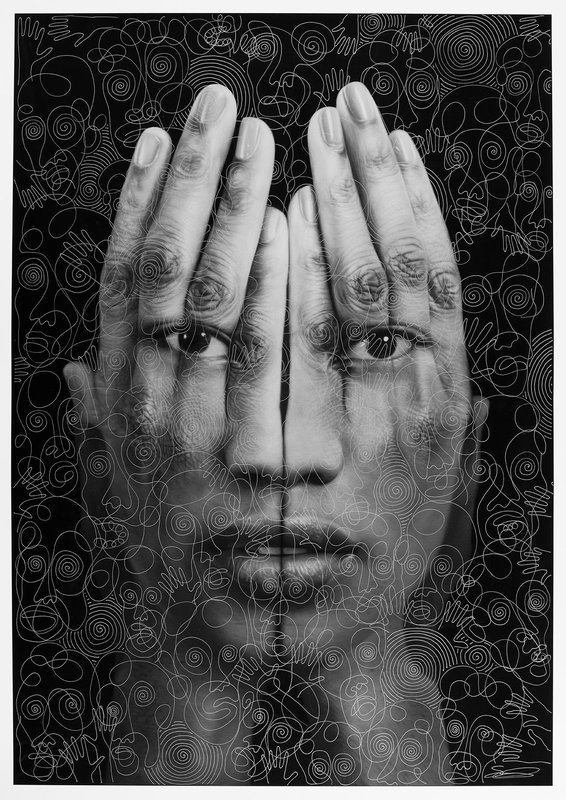

Tigran Tsitoghdzyan. Black Mirror, 2018.

Tigran Tsitoghdzyan. Black Mirror, 2018.