by Scott F. Aikin and Robert B. Talisse

Here’s a reasonable rule for critical discussion: all views for consideration should receive the same degree of scrutiny. Subjecting one account to a low level of critical evaluation, but another to a higher level, is not only unfair, but it clearly risks incorrect outcomes. In retrospect, it is easy to see how such a shift can occur, especially when the claims on offer are controversial and when one sees some in the conversation as adversaries or allies. When a person we despise says something, we might even positively want them to be wrong. So, when they say something anodyne, like the sky is blue, we may be motivated to reply in the following fashion:

Oh yeah? Well, sometimes, it’s red, purple, and yellow. That’s called sunset. And sometimes, it’s grey. That’s called overcast. Oh, and sometimes, it’s just black. That’s called night. Nice job overgeneralizing from sunny and cloudless days, you jerk.

You get the picture. Yet when a friendly interlocutor offers up the sky is blue, we tend to treat it with the modest degree of scrutiny that it calls for – as a general statement, with many exceptions. No problem.

One reason why the shift in critical scrutiny is hard to detect in situ is that it happens over time and with a background assumption about the exchange established in the process. This overall pattern we call the clearing the decks fallacy. Here’s how it unfolds. Step 1: Subject your opponents to the highest degree of scrutiny. Step 2: Once it is clear that the opponent’s views cannot satisfy that degree of scrutiny, conclude that they are nonviable and unsalvageable. Step 3: Pronounce your own view, but in a way that assumes that the appropriate degree of scrutiny has greatly diminished (after all, the opposition has been refuted). Step 4: If objections do appear, reply with a reminder of Step 2 – that the alternatives have been eliminated, so objections that must be based on their assumptions are undercut. It’s a neat dialectical strategy: one clears the decks of one’s opposition by adopting an unforgiving critical stance, but then one proceeds as if those same standards are inappropriate when it comes time to articulate one’s own view. In short, one applies demanding standards to clear the decks of one’s opposition, but then retracts those standards when presenting one’s own position once the opposition has been eliminated. Two features of the clearing the decks fallacy deserve emphasis. Read more »

For the past year or so there have been a considerable number of cases of teachers or authors or journalists who have been threatened with sanctions, had sanctions imposed, or lost their positions, because of articles they wrote or statements they made as part of their occupations. Many of these cases involved the appearance of the N-word in their speech or written work. Here are some of them.

For the past year or so there have been a considerable number of cases of teachers or authors or journalists who have been threatened with sanctions, had sanctions imposed, or lost their positions, because of articles they wrote or statements they made as part of their occupations. Many of these cases involved the appearance of the N-word in their speech or written work. Here are some of them. Please, See My Innocence

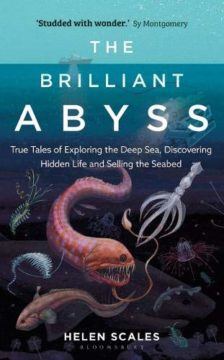

Please, See My Innocence Marine biologist Helen Scales’ book, The Brilliant Abyss: True Tales of Exploring the Deep Sea, Discovering Hidden Life and Selling the Seabed is a triumph. The four major sections in the book, ‘Explore’, ‘Depend’, ‘Exploit’ and ‘Preserve’ are indicators of the breadth of issues addressed in the book: the variety of life forms in the different levels of the oceans; the significance of the oceans to life on the planet; the various ways in which human activity exploits the oceans resources, and concludes with her ideas about how to prevent the ocean from becoming just another area of resources of the planet for exploitation by human beings.

Marine biologist Helen Scales’ book, The Brilliant Abyss: True Tales of Exploring the Deep Sea, Discovering Hidden Life and Selling the Seabed is a triumph. The four major sections in the book, ‘Explore’, ‘Depend’, ‘Exploit’ and ‘Preserve’ are indicators of the breadth of issues addressed in the book: the variety of life forms in the different levels of the oceans; the significance of the oceans to life on the planet; the various ways in which human activity exploits the oceans resources, and concludes with her ideas about how to prevent the ocean from becoming just another area of resources of the planet for exploitation by human beings. Sughra Raza. River Magic. May, 2021.

Sughra Raza. River Magic. May, 2021. Small poetry presses are the gold dust of the publishing world, glittering yet easy to miss. And of enduring cumulative value.

Small poetry presses are the gold dust of the publishing world, glittering yet easy to miss. And of enduring cumulative value.

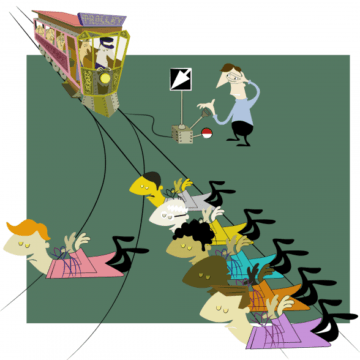

The first part of the original trolley problem goes like this. A runaway trolley is careening towards five people tied to the tracks. There’s a lever in front of you that could divert it onto a second set of tracks. Unfortunately, there is also a person tied to those tracks. You can either do nothing and let five people die or throw the switch and kill one person – but save the five. What do you do?

The first part of the original trolley problem goes like this. A runaway trolley is careening towards five people tied to the tracks. There’s a lever in front of you that could divert it onto a second set of tracks. Unfortunately, there is also a person tied to those tracks. You can either do nothing and let five people die or throw the switch and kill one person – but save the five. What do you do?

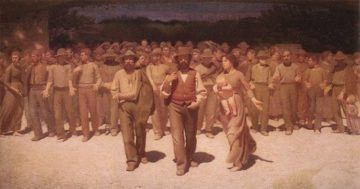

How should people on the ‘progressive’ side of politics view patriotism? That question continues to vex those who would connect with what they suppose are the feelings of the bulk of the population. The answer will vary a good deal according to which country we are considering – the French left, for instance, has a very different relationship to la patrie to that of the US or the UK. In the case of the former, the side cast as traitors has historically been seen as the right. In the USA, at least in the second half of the 20th century it has been very different: those who protested against the Vietnam war were cast as the anti patriots. And today, we still hear that the left ‘hates our country’. The accusation is a damaging one, and has been wielded with glee by conservatives whenever they have the chance. So there is a tricky task for the left, it seems: to be seen as with and not against the mass of people in their identification with the nation and its history, without abandoning an internationalist perspective that rises above the narrow nationalism of the conservative.

How should people on the ‘progressive’ side of politics view patriotism? That question continues to vex those who would connect with what they suppose are the feelings of the bulk of the population. The answer will vary a good deal according to which country we are considering – the French left, for instance, has a very different relationship to la patrie to that of the US or the UK. In the case of the former, the side cast as traitors has historically been seen as the right. In the USA, at least in the second half of the 20th century it has been very different: those who protested against the Vietnam war were cast as the anti patriots. And today, we still hear that the left ‘hates our country’. The accusation is a damaging one, and has been wielded with glee by conservatives whenever they have the chance. So there is a tricky task for the left, it seems: to be seen as with and not against the mass of people in their identification with the nation and its history, without abandoning an internationalist perspective that rises above the narrow nationalism of the conservative.

Talking about “The Enlightenment”, when understood as something like “an intellectual and philosophical movement that dominated the world of ideas in Europe during the 17th and 18th centuries” (thanks,

Talking about “The Enlightenment”, when understood as something like “an intellectual and philosophical movement that dominated the world of ideas in Europe during the 17th and 18th centuries” (thanks,

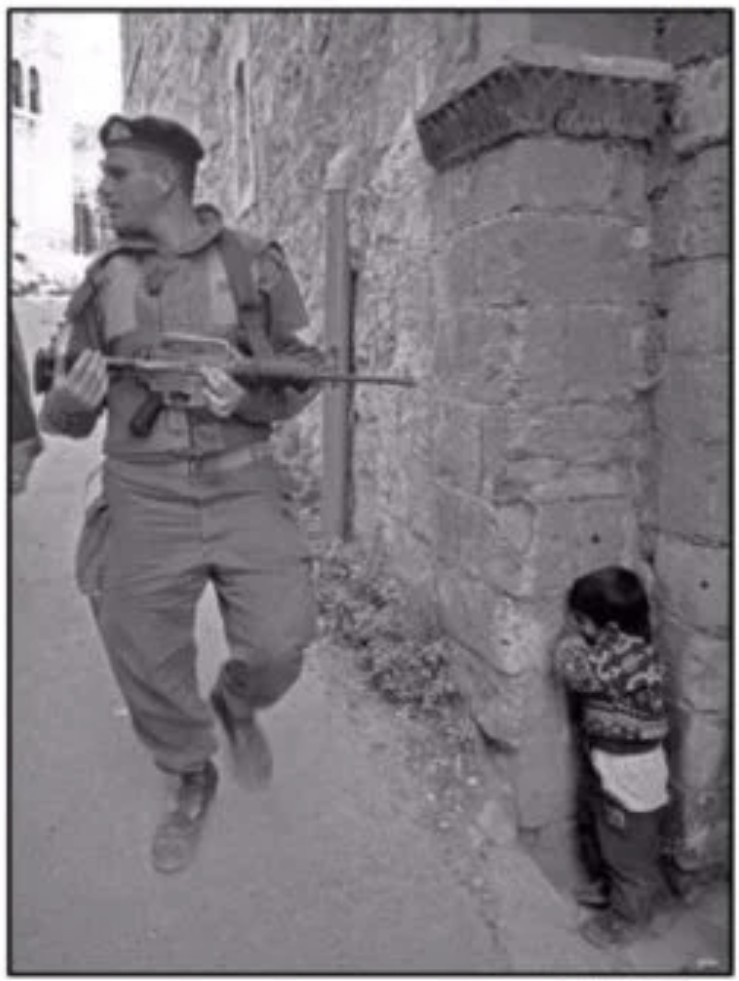

Sughra Raza. Untitled, April 2021.

Sughra Raza. Untitled, April 2021.