by Martin Butler

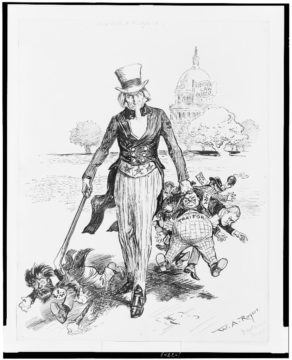

Individualism has been blamed for the break up of communities, personal alienation and rampant western consumerism. At the same time, with its focus on liberty and human rights, it is lauded as the crowning glory of western culture. How do we come to terms with this paradox?

Individualism feels natural to the modern western mind. We balk at the idea of living according to the preconceptions of tradition, religion or authoritarian elites. Individualism is promoted in diverse lifestyles, chosen identities, family structures and types of relationships, in everything from artistic and popular taste to our belief systems and ways of making money. This trend has been turbo-charged by the Internet, as now we all have a mouthpiece through which to proclaim our choices and opinions. The philosopher Charles Taylor recognises that modern western culture is not uniform but identifies three ways in which it embraces individualism: “it prizes autonomy; it gives an important place to self-exploration, in particular of feelings; and its visions of the good life generally involve personal commitment.”[1] He also points out that the political expression of this individualism comes in the modern focus on rights.

On the other hand, individuals need society, but there is a sense in which individualism is anti-social and works against community. Historically, societies have placed limits on autonomy and rights, on personal commitments and even self-exploration. Liberalism was supposed to be the solution through building a society on the acknowledgment of the value of individualism, and so was designed to cope with conflict and difference – this, after all, is the essence of Mill’s harm principle. The modern thinker who has gone furthest in exploring the consequences of full-blown individualism, however, is Robert Nozick. Starting from the simple premise that individuals are autonomous beings with rights, Nozick struggles to form anything we would recognise as a fully functioning society, famously concluding that “Taxation of earnings from labor is on a par with forced labour”.[2] So he avoids the paradox simply by downplaying the social nature of human existence and embracing the individualistic. His insistence on individual rights is so strong that the group can make next to no claims on anyone without their explicit consent. His minimal state does no more than protect these basic rights. Read more »

George Saunders’ recent book, A Swim in a Pond in the Rain, is the most enjoyable and enlightening book on literature I have ever read.

George Saunders’ recent book, A Swim in a Pond in the Rain, is the most enjoyable and enlightening book on literature I have ever read.

It seems as if everyone in the wine industry proclaims that wine tasting is subjective. Wine educators encourage consumers to trust their own palates. “There is no right or wrong when tasting wine,” I heard a salesperson say recently. “Don’t put much stock in what the critics say,” said a prominent winemaker to a large audience when discussing the aromas to be found in a wine. The point is endlessly promoted by wine writers. Wine tasting is wholly subjective. There is no right answer to what a wine tastes like and no standards of correctness for judging wine quality.

It seems as if everyone in the wine industry proclaims that wine tasting is subjective. Wine educators encourage consumers to trust their own palates. “There is no right or wrong when tasting wine,” I heard a salesperson say recently. “Don’t put much stock in what the critics say,” said a prominent winemaker to a large audience when discussing the aromas to be found in a wine. The point is endlessly promoted by wine writers. Wine tasting is wholly subjective. There is no right answer to what a wine tastes like and no standards of correctness for judging wine quality.

On February 18, 2021, NASA landed Perseverance rover on the surface of Mars. Perseverance is the latest of some twenty probes that NASA has sent to bring back detailed information about our neighboring planet, beginning with the Mariner spacecraft fly-by in 1965, which took the first closeup photograph. Though blurry by today’s standards, those grainy images helped ignite widespread wonder and fantasy about space exploration, not long before Star Trek also debuted on television. By the 1970s, science-fiction storytelling was moving from the margins of pop-culture into the mainstream in film and television—and so followed generations of kids, like myself, who grew up expecting off-world adventurism and alien encounters almost as much as we anticipated the invention of video-phones and pocket computers and household robots, as our conceptual bounds for the human story were pushed ever farther outward.

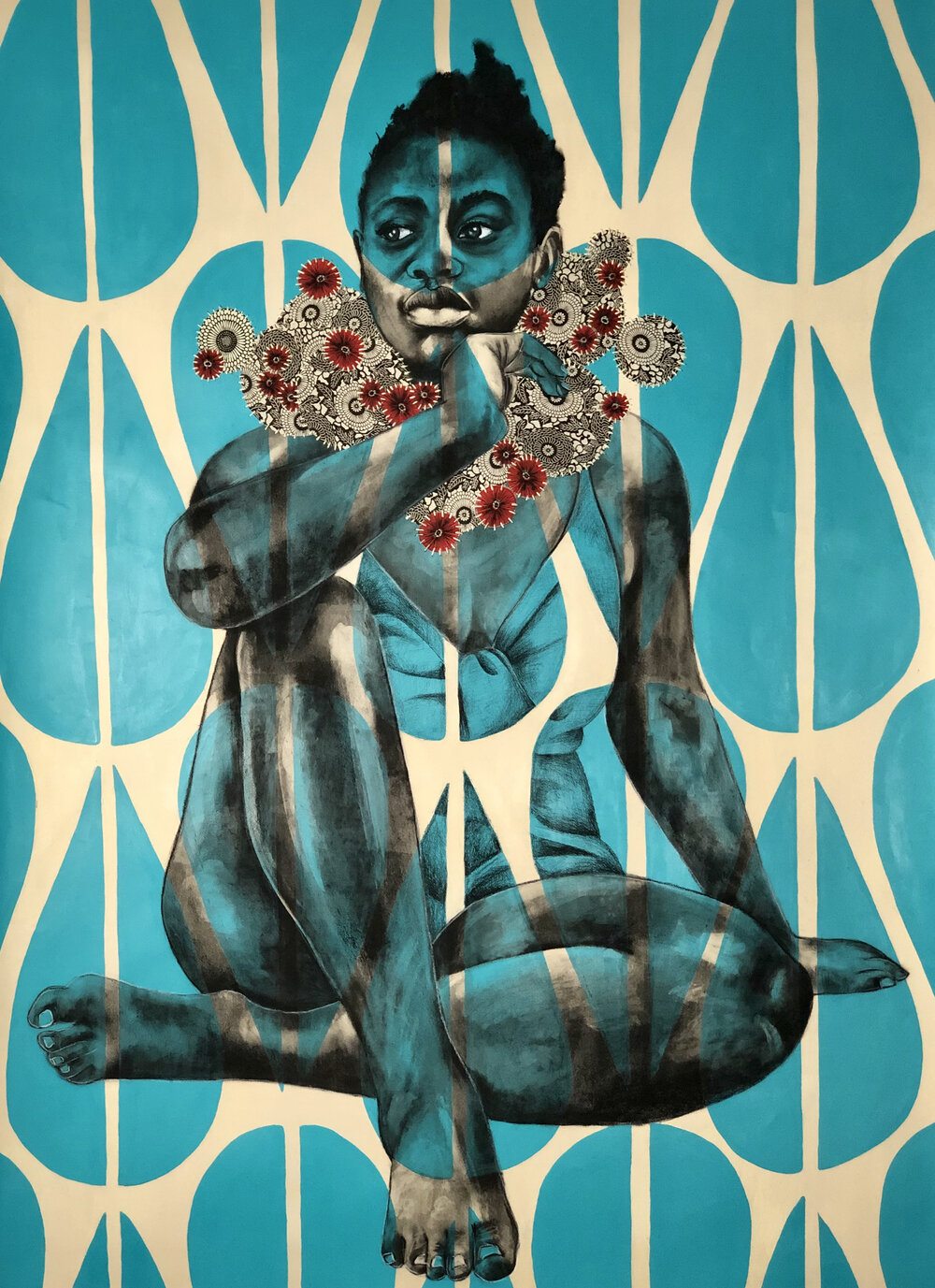

On February 18, 2021, NASA landed Perseverance rover on the surface of Mars. Perseverance is the latest of some twenty probes that NASA has sent to bring back detailed information about our neighboring planet, beginning with the Mariner spacecraft fly-by in 1965, which took the first closeup photograph. Though blurry by today’s standards, those grainy images helped ignite widespread wonder and fantasy about space exploration, not long before Star Trek also debuted on television. By the 1970s, science-fiction storytelling was moving from the margins of pop-culture into the mainstream in film and television—and so followed generations of kids, like myself, who grew up expecting off-world adventurism and alien encounters almost as much as we anticipated the invention of video-phones and pocket computers and household robots, as our conceptual bounds for the human story were pushed ever farther outward. Delita Martin. Rain Falls From The Lemon Tree. 2020

Delita Martin. Rain Falls From The Lemon Tree. 2020 It’s been 40 years this past month since the election of François Mitterrand as President of France. Today, June 21, is the day chosen by his first Minister of Culture for the

It’s been 40 years this past month since the election of François Mitterrand as President of France. Today, June 21, is the day chosen by his first Minister of Culture for the

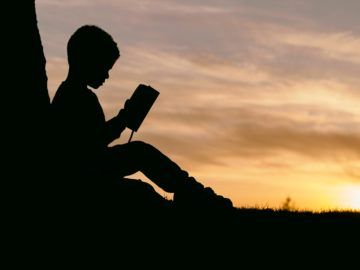

When we were young, most of us indulged in the speculation, “What do I want to be when I grow up?” Many of us said things like a firefighter, a doctor, a nurse, or a teacher. As children, we instinctively looked at the world around us and recognized the careers that seemed to have purpose and meaning, and that seemed to make the world a better place. I can’t imagine that many 5-years olds dreamed of being paper pushers or spending their days doing data entry. But we grow up. People around us have expectations for us; we have expectations for ourselves. We might have academic challenges, financial needs, family obligations. We see the world and the careers open to us as more diverse and as more challenging than the Fisher-Price Little People figures that characterize the world for a child. And so, many of us lose that childhood idealism and just get a job, get on the career ladder, put our noses to the grindstone.

When we were young, most of us indulged in the speculation, “What do I want to be when I grow up?” Many of us said things like a firefighter, a doctor, a nurse, or a teacher. As children, we instinctively looked at the world around us and recognized the careers that seemed to have purpose and meaning, and that seemed to make the world a better place. I can’t imagine that many 5-years olds dreamed of being paper pushers or spending their days doing data entry. But we grow up. People around us have expectations for us; we have expectations for ourselves. We might have academic challenges, financial needs, family obligations. We see the world and the careers open to us as more diverse and as more challenging than the Fisher-Price Little People figures that characterize the world for a child. And so, many of us lose that childhood idealism and just get a job, get on the career ladder, put our noses to the grindstone. The desire to turn failure into a learning opportunity is often generous, and an important way of dealing with the trials and tribulations of life. I first became aware of it as a frequent trope in start-up culture, where, influenced by practices in software development where trying things out and failing is the quickest way to get to something of value, we are constantly subject to exhortations to “fail fast and fail forward”. Many workplaces now lionise (whether sincerely or not is another matter) the importance of learning through failure, and of creating environments that encourage this.

The desire to turn failure into a learning opportunity is often generous, and an important way of dealing with the trials and tribulations of life. I first became aware of it as a frequent trope in start-up culture, where, influenced by practices in software development where trying things out and failing is the quickest way to get to something of value, we are constantly subject to exhortations to “fail fast and fail forward”. Many workplaces now lionise (whether sincerely or not is another matter) the importance of learning through failure, and of creating environments that encourage this.