by David J. Lobina

A number of issues in the study of nationalism ought to be widely accepted nowadays, most notably perhaps the claim that political nationalism – the idea that a citizen pledges allegiance to a nation-state rather than to a village or a town – is a modern phenomenon. After all, nationalism properly takes hold in a territory when modern tools such as universal schooling are employed to produce a national identity – the inhabitants of a territory must speak the same language and recognise a common culture if a nation is to surface – and this is a product of the last 200 years. A national identity doesn’t come about on its own.

A number of issues in the study of nationalism ought to be widely accepted nowadays, most notably perhaps the claim that political nationalism – the idea that a citizen pledges allegiance to a nation-state rather than to a village or a town – is a modern phenomenon. After all, nationalism properly takes hold in a territory when modern tools such as universal schooling are employed to produce a national identity – the inhabitants of a territory must speak the same language and recognise a common culture if a nation is to surface – and this is a product of the last 200 years. A national identity doesn’t come about on its own.

A particularly prominent aspect of how political nationalism does actually take hold in a large territory involves the central role a common language typically plays in the establishment of a national identity, a topic that has been at the heart of many studies of nationalism, though it is rarely treated satisfactorily.

Take two examples from the field of history, chosen almost at random but which nonetheless showcase some of the issues at stake. The author and historian Adrian Hastings once argued that England was already a nation-state in the 11th century, which he claimed was the case, in part, because of ‘the stabilising of an intellectual and linguistic world through a thriving vernacular literature’,[i] while the more modern historian Caspar Hirschi has recently paid attention to linguistic exchanges between different regions of Europe in the Middle Ages in order to probe what these interactions can tell us about how medieval peoples thought of each other. In particular, Hirschi points out that, as a case in point, hardly anyone in medieval Italy could understand what the merchants ‘coming from the north of the Alps were saying’, and it was precisely because of this that these people ‘were able to perceive the strange sounds as a ‘common’ language’, presumably thus identifying a common people to boot.[ii]

Such discourse is common enough and not too dissimilar to how laypeople talk of matters to do with language; it is, however, rather misleading and can sometimes lead scholars astray. In this sense, the study of nationalism could certainly benefit from the input of professional linguists. Read more »

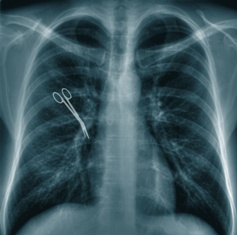

When I finished my residency in 1980, I chose Medical Oncology as my specialty. I would treat patients with cancer.

When I finished my residency in 1980, I chose Medical Oncology as my specialty. I would treat patients with cancer.

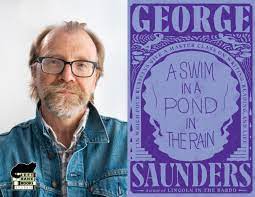

George Saunders’ recent book, A Swim in a Pond in the Rain, is the most enjoyable and enlightening book on literature I have ever read.

George Saunders’ recent book, A Swim in a Pond in the Rain, is the most enjoyable and enlightening book on literature I have ever read.