by Nicola Sayers

To be clear: I was snooty, too. I first saw colour-coordinated bookshelves in my friend’s home, and I have to admit that, even then, I liked the look. Each neatly stacked shelf, bright and orderly. It reminded me of the new packets of felt-tipped pens I used to love getting as a kid. But in the same moment, a well-trained habit of literary condescension kicked in (I blame grad school – at heart I’m more an enthusiast than a critic, but they beat that out of you pretty quickly) and I heard myself asking a series of cringey questions. Questions designed to belittle, to declare my own bookishness in some way superior to my friend’s. But how do you find the book you’re looking for? Isn’t it weird to separate books by the same author? How do they all look so clean? (Subtext: do you even read these books?)

But several years and a mild-to-moderate Pinterest addiction later, I found myself one rainy morning, stuck at home with a baby whose sweet smile did not, on that day, quite make up for her conversational shortcomings, and in need of some cheer. And so it was that, a few frenzied hours later, my husband came home to find all of our books rearranged according to colour. (His shelves, he’d no doubt want me to point out, have since been returned to what he views as their rightful order – yes, although we share children, a home and a bank account, our respective bookshelves are still clearly demarcated).

My reasoning behind the reorder was admittedly entirely superficial, but the effect was surprising. I look at, engage with, and even re-read my books much more since the change. Before, I had a feeling that I knew what was there: the classics, my Frankfurt School lineup, my ever-expanding gang of contemporary female writers, and so on. Now, my book collection is both more and less familiar to me. The pops of colour draw my eyes in more frequently, but I find that the thematic disorder left in the wake of the coloured order is also strangely welcome. I not only look at the books more often, I also look at them anew. Read more »

In spite of my abiding interest in literature when I came to college I was vaguely inclined to major in History. In the long break between school and college I chanced upon two books of Marxist history which opened me to a new vista of looking at history. The first was Maurice Dobb’s Studies in the Development of Capitalism. This book showed me that there is a discernible pattern in the jumble of facts in history, which attracted me. Soon after, I read a lesser Marxist history book, A.L. Morton’s People’s History of England which showed me how recasting the old widely-known history of England from the people’s perspective gives you new insights. These books whetted my appetite to read more of Marxist history.

In spite of my abiding interest in literature when I came to college I was vaguely inclined to major in History. In the long break between school and college I chanced upon two books of Marxist history which opened me to a new vista of looking at history. The first was Maurice Dobb’s Studies in the Development of Capitalism. This book showed me that there is a discernible pattern in the jumble of facts in history, which attracted me. Soon after, I read a lesser Marxist history book, A.L. Morton’s People’s History of England which showed me how recasting the old widely-known history of England from the people’s perspective gives you new insights. These books whetted my appetite to read more of Marxist history. The events in Afghanistan over the last week are being seen as yet another “hinge moment” in history. The images of helicopters evacuating personnel from embassies and people chasing aircraft in desperation to get on them have been seared into the memories of all who have seen them. As a person from the region (Pakistan), a student of history, and as someone interested in the current state of the world, I too have watched these events with a mixture of amazement, trepidation, horror, and perplexity. It is not clear yet whether “hope” or “fear” – or both – should be added to that list. The things I say in this piece are just the thoughts and speculations of a non-expert lay person trying to make sense of an obscure situation. As will be obvious from the rest of this piece, for all the pain and suffering the new situation in Afghanistan will bring to people in Afghanistan, I think that the American decision to withdraw was the only rational choice. The alternative of staying on for years – perhaps decades – to build a better Afghanistan would just be another exercise in paternalistic colonialism. However, the way the withdrawal is happening is a great failure of American leadership and the blame for that lies mainly with the American policies of the last two decades. Perhaps its biggest failure was in not preparing Afghanistan for this day that was sure to come sooner or later. Now the Afghan people – especially women – will pay a price for that failure, but it may also come back to haunt the United States and other great powers. It has happened before….

The events in Afghanistan over the last week are being seen as yet another “hinge moment” in history. The images of helicopters evacuating personnel from embassies and people chasing aircraft in desperation to get on them have been seared into the memories of all who have seen them. As a person from the region (Pakistan), a student of history, and as someone interested in the current state of the world, I too have watched these events with a mixture of amazement, trepidation, horror, and perplexity. It is not clear yet whether “hope” or “fear” – or both – should be added to that list. The things I say in this piece are just the thoughts and speculations of a non-expert lay person trying to make sense of an obscure situation. As will be obvious from the rest of this piece, for all the pain and suffering the new situation in Afghanistan will bring to people in Afghanistan, I think that the American decision to withdraw was the only rational choice. The alternative of staying on for years – perhaps decades – to build a better Afghanistan would just be another exercise in paternalistic colonialism. However, the way the withdrawal is happening is a great failure of American leadership and the blame for that lies mainly with the American policies of the last two decades. Perhaps its biggest failure was in not preparing Afghanistan for this day that was sure to come sooner or later. Now the Afghan people – especially women – will pay a price for that failure, but it may also come back to haunt the United States and other great powers. It has happened before….

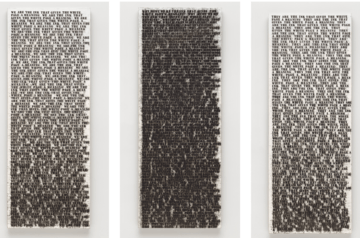

Sughra Raza. Temple Wall Philosophy. Galle, Sri Lanka, 2010.

Sughra Raza. Temple Wall Philosophy. Galle, Sri Lanka, 2010.

Unlike her previous exhibit, James chose not to explicitly market

Unlike her previous exhibit, James chose not to explicitly market

The view that everyone who is capable has a basic duty to work and not be idle is the main tenet of what we call the work ethic. Closely related to this are two other ideas:

The view that everyone who is capable has a basic duty to work and not be idle is the main tenet of what we call the work ethic. Closely related to this are two other ideas: