by Paul Braterman

We all know the story. Socrates has been told by the oracle that he is wisest of men, but he considers that he himself knows nothing. Puzzled, he takes to cross-examining his fellow Athenians about their beliefs, and time and again finds that they will not bear examination. As a result, he is indicted on trumped-up charges of impiety and corrupting the young. After a trial in which he eloquently defends his behaviour, he is condemned to death. A martyr to freedom of expression, and a shocking example of democracy suppressing dissent. Surely there is more to the story than that? Indeed there is.

I am not about to commit the folly of denying the greatness of Socrates. We still, twentyfour cenuries later, praise his methods of investigation. I myself have used an argument taken directly from one of Plato’s Socratic dialogues. The topic was practical ethics, Socrates’ speciality; and the technique used, questioning assumed certainties, his favourite tactic.

Here’s what happened. A few years ago, I was involved in a moderately successful campaign [1] to reduce the statutory role of the Churches in Scotland’s local authority education committees. The Church of Scotland attempted to justify its privileged position by pointing to its distinctive Christian ethos. In reply, I pointed out that to the extent that this ethos is generally shared, we do not need any Church to promote it, while to the extent that it is specific to Christianity, the Churches have no right to impose it on the rest of us.

My reasoning derives directly from Socrates, in The Euthyphro, where Socrates challenges Euthyphro to define pious behaviour. Read more »

The gender wage gap is a well-documented phenomenon. Many are familiar with the claim that women earn 80 cents on the dollar. A more precise statement would be something like, “In the U.S., according to

The gender wage gap is a well-documented phenomenon. Many are familiar with the claim that women earn 80 cents on the dollar. A more precise statement would be something like, “In the U.S., according to

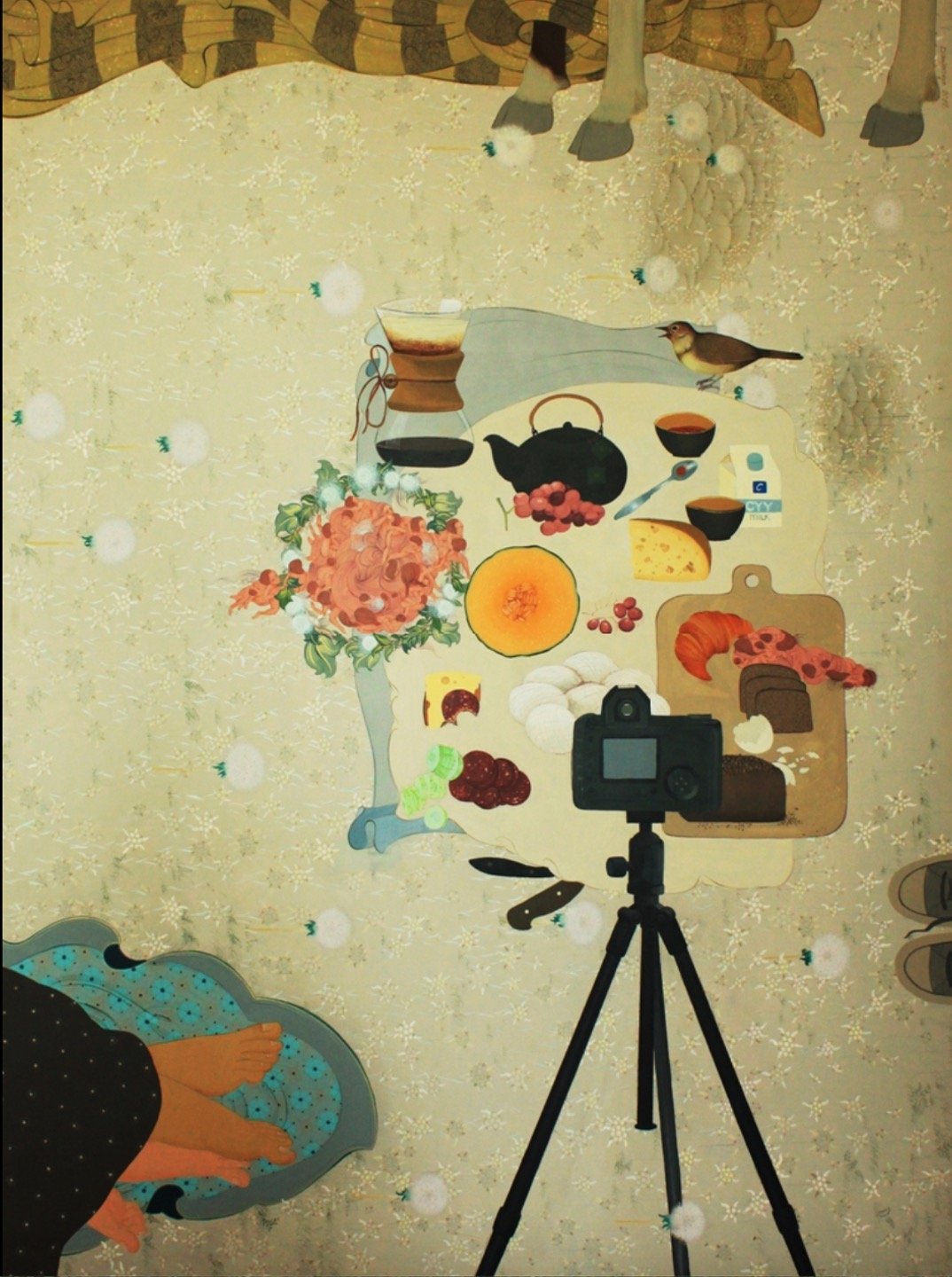

Uuriintuya Dagvasambuu. Aabam Beebem, 2019.

Uuriintuya Dagvasambuu. Aabam Beebem, 2019.

1859 was not a bad year for publishing in Britain. Books that came out that year included Darwin’s On the Origin of Species, John Stuart Mill’s On Liberty, and George Eliot’s Adam Bede. The first installments of Dickens’ A Tale of Two Cities and Wilkie Collins’ The Woman in White also made their appearance. And Samuel Smiles published Self-Help.

1859 was not a bad year for publishing in Britain. Books that came out that year included Darwin’s On the Origin of Species, John Stuart Mill’s On Liberty, and George Eliot’s Adam Bede. The first installments of Dickens’ A Tale of Two Cities and Wilkie Collins’ The Woman in White also made their appearance. And Samuel Smiles published Self-Help.

According to the website Rotten Tomatoes, there are four types of movies: good-good movies, good-bad movies, bad-good movies, and bad-bad movies. These types can be identified using the Rotten Tomatoes score for each movie, particularly the relationship between the critics’ score and the audience’s score. Let me explain. Rotten Tomatoes is a website that collects movie reviews and assigns them a rating of either “fresh” (if the review is positive) or “rotten” (if the review is negative). It then calculates the percentage of fresh reviews and assigns this as a score to the movie. If the score is 60% or greater, the film itself is considered fresh, whereas if the score is lower than 60%, the film is rotten. This is a useful way of rating a movie, but there’s a problem here, too. Let’s imagine every reviewer gives a movie three out of four stars, indicating a good film but not a great one. These reviews would all be classified as fresh, and the film would receive a misleadingly high score of 100% (The Terminator has a 100% rating, for example, while The Godfather does not). Let’s imagine another film receives all two out of four-star reviews. These would be classified as rotten, and the film would receive a rating of 0%, indicating one of the worst movies of all time. But the movie wouldn’t really be that bad.

According to the website Rotten Tomatoes, there are four types of movies: good-good movies, good-bad movies, bad-good movies, and bad-bad movies. These types can be identified using the Rotten Tomatoes score for each movie, particularly the relationship between the critics’ score and the audience’s score. Let me explain. Rotten Tomatoes is a website that collects movie reviews and assigns them a rating of either “fresh” (if the review is positive) or “rotten” (if the review is negative). It then calculates the percentage of fresh reviews and assigns this as a score to the movie. If the score is 60% or greater, the film itself is considered fresh, whereas if the score is lower than 60%, the film is rotten. This is a useful way of rating a movie, but there’s a problem here, too. Let’s imagine every reviewer gives a movie three out of four stars, indicating a good film but not a great one. These reviews would all be classified as fresh, and the film would receive a misleadingly high score of 100% (The Terminator has a 100% rating, for example, while The Godfather does not). Let’s imagine another film receives all two out of four-star reviews. These would be classified as rotten, and the film would receive a rating of 0%, indicating one of the worst movies of all time. But the movie wouldn’t really be that bad. Is loneliness a choice? Is love?

Is loneliness a choice? Is love? Presidency College had a good Department of Economics and Political Science. I’d say that the teaching standard at my time there would compare quite favorably with the standard I found later when teaching undergraduate classes in Berkeley. I remember in my first lecture in Berkeley in a large undergraduate class I was using some bit of calculus. After my class a female student came to see me to complain about the use of calculus in class. I told her that I was not using any advanced calculus, so if she brushed up her high school-level calculus she should have no difficulty in following the class. She said that in her high school in Carmel, a California coastal town, there was the option to take either calculus or yoga, and she had chosen the latter. I told her, unhelpfully, that this was a choice unheard-of in the land of yoga, India, and, I thought to myself, certainly in Presidency College.

Presidency College had a good Department of Economics and Political Science. I’d say that the teaching standard at my time there would compare quite favorably with the standard I found later when teaching undergraduate classes in Berkeley. I remember in my first lecture in Berkeley in a large undergraduate class I was using some bit of calculus. After my class a female student came to see me to complain about the use of calculus in class. I told her that I was not using any advanced calculus, so if she brushed up her high school-level calculus she should have no difficulty in following the class. She said that in her high school in Carmel, a California coastal town, there was the option to take either calculus or yoga, and she had chosen the latter. I told her, unhelpfully, that this was a choice unheard-of in the land of yoga, India, and, I thought to myself, certainly in Presidency College. I live on an island. It happens to be a rather densely populated island, with a surface that seems largely covered by steel, masonry, glass, and architectural curtain wall, with nary a coconut or palm tree in sight. Still, it’s an island.

I live on an island. It happens to be a rather densely populated island, with a surface that seems largely covered by steel, masonry, glass, and architectural curtain wall, with nary a coconut or palm tree in sight. Still, it’s an island.

“The Iliad, or The Poem of Force” is a now-canonical lyrical-critical essay by the French anarchist and Christian mystic, Simone Weil. In it, Weil critiques the

“The Iliad, or The Poem of Force” is a now-canonical lyrical-critical essay by the French anarchist and Christian mystic, Simone Weil. In it, Weil critiques the

In the late 1960s and early 70s, Pocatello, Idaho, was one of the fastest growing towns in the United States. It was, and still is, a bland little place in the arid montane region of the American West. I don’t know why it mushroomed then; it has since stagnated and even shrunk. Nevertheless, the summer I turned four, my family was one among many who moved to reside there. Our little red brick house, still unfinished on the day we moved in, was the last house at the end of a newly laid street, still half-empty of houses. Our street stretched like a solitary finger into a kind of wilderness, an austere, high-desert landscape that surrounded our foundling residential colony. From my vantage as a child, preoccupied with the flowers, spiders, and thistles that stuck to my socks, I would see this place transformed.

In the late 1960s and early 70s, Pocatello, Idaho, was one of the fastest growing towns in the United States. It was, and still is, a bland little place in the arid montane region of the American West. I don’t know why it mushroomed then; it has since stagnated and even shrunk. Nevertheless, the summer I turned four, my family was one among many who moved to reside there. Our little red brick house, still unfinished on the day we moved in, was the last house at the end of a newly laid street, still half-empty of houses. Our street stretched like a solitary finger into a kind of wilderness, an austere, high-desert landscape that surrounded our foundling residential colony. From my vantage as a child, preoccupied with the flowers, spiders, and thistles that stuck to my socks, I would see this place transformed.