by Peter Wells

Corporal punishment is a sickening and ugly procedure. Apart from the fact that one person is deliberately hurting another (usually smaller) at close quarters, it is often associated with anger, and even sadism. It is too often administered without reflection, too soon after a perceived offence has been committed. It is humiliating for the victim, especially if done in public, possibly causing lasting resentment and/or low self-esteem. It may encourage the development of violent attitudes among its recipients. The recent efforts to outlaw it are therefore humane and well-intentioned and, as far as they go, praiseworthy.

Unless, as in the case of Capital Punishment (q.v.), the alternatives turn out to be worse.

Let us look in turn at three loci in which corporal punishment has been used (and is now outlawed) in the UK: school, the home, and the criminal justice system.

As a teacher for half a century, I’ve given a lot of thought to how classes might be managed and children’s misdemeanours dealt with, and much has changed in that time. In the past, in addition to formal canings or beatings, administered by a headteacher or a responsible deputy, teachers in the classroom were given unofficial licence to strike children – which, as they were usually sitting in desks, meant hitting the part of the body most exposed: the head. Sometimes they threw things – chalk, if you were lucky. Aside from the obvious physical danger of this practice, it was inconsistent and suffered from flawed motivations. Teachers developed irrational hatreds for particular students, and therefore punished them with exceptional savagery. They were sometimes angry for some extraneous reason. The relationship between the crime and the punishment was ill-defined. I can remember dropping off to sleep in a warm classroom after lunch, and waking to find my head ringing from a blow, my spectacles broken on the floor beside me, and the red face of my French teacher a few inches from mine, roaring with rage. QED – it was a long time ago, and I still remember it vividly! And I particularly resented it because I was a keen student, who normally kept to the rules. Read more »

As a consequential Supreme Court term gets underway, with potentially large consequences for women’s autonomy and health, it’s worth thinking about the ways in which judges do or do not consider the real world consequences of their decisions.

As a consequential Supreme Court term gets underway, with potentially large consequences for women’s autonomy and health, it’s worth thinking about the ways in which judges do or do not consider the real world consequences of their decisions.

I knew that Cambridge was by the river Cam, but the first day when I looked for it I could not find it. From the map I knew that on my way to the Economics Department I had to cross it, I stopped and looked around but I could not see anything like a river. Then I asked a passerby, and he pointed to what I had thought was a small ditch or a canal. It was difficult to take it as a river, as in India I was used to much bigger rivers. Over time, however, I saw the serene beauty of this mini-river, with its placid water by the weeping willows, the swans, gliding boats and all.

I knew that Cambridge was by the river Cam, but the first day when I looked for it I could not find it. From the map I knew that on my way to the Economics Department I had to cross it, I stopped and looked around but I could not see anything like a river. Then I asked a passerby, and he pointed to what I had thought was a small ditch or a canal. It was difficult to take it as a river, as in India I was used to much bigger rivers. Over time, however, I saw the serene beauty of this mini-river, with its placid water by the weeping willows, the swans, gliding boats and all.

The well-known counterintuitive Monty Hall problem continues to baffle people if the emails I receive are any indication. A meta-problem is to understand why so many people are unconvinced by the various solutions. Sometimes people even cite the large number of the unconvinced as proof that the solution is a matter of real controversy, just as in politics an inconvenient fact, such as the ubiquity of Covid-19, is obscured by fake controversies.

The well-known counterintuitive Monty Hall problem continues to baffle people if the emails I receive are any indication. A meta-problem is to understand why so many people are unconvinced by the various solutions. Sometimes people even cite the large number of the unconvinced as proof that the solution is a matter of real controversy, just as in politics an inconvenient fact, such as the ubiquity of Covid-19, is obscured by fake controversies.

It had been a long time since I thought about lawns. I don’t mean in a grand philosophical sense, or the stoned contemplation of a single blade of grass. I mean thought about them at all. Before moving to Mississippi we had lived in Vancouver for 13 years, where we felt lucky to have a place to store our toothbrushes and maybe an extra pair of slacks; we really hit the jackpot when we acquired a postage-stamp-sized balcony on which we could murder tomato plants. Actual yards were out of the question for anyone who hadn’t bought a house on the west end of town 30 years ago; by the time we moved to Vancouver in 2006 as a tenure-track assistant professor and a trailing-spouse adjunct, it was already clear that we would never own a lawn.

It had been a long time since I thought about lawns. I don’t mean in a grand philosophical sense, or the stoned contemplation of a single blade of grass. I mean thought about them at all. Before moving to Mississippi we had lived in Vancouver for 13 years, where we felt lucky to have a place to store our toothbrushes and maybe an extra pair of slacks; we really hit the jackpot when we acquired a postage-stamp-sized balcony on which we could murder tomato plants. Actual yards were out of the question for anyone who hadn’t bought a house on the west end of town 30 years ago; by the time we moved to Vancouver in 2006 as a tenure-track assistant professor and a trailing-spouse adjunct, it was already clear that we would never own a lawn.

Robert Dash. Flower Bud of the Arbequina Olive Tree (black olives).

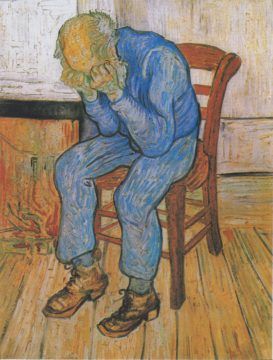

Robert Dash. Flower Bud of the Arbequina Olive Tree (black olives). What is it to be twenty? Forty? Sixty? Eighty? These points that mark the four quarters of a life — fifths if you’re lucky, larger portions if you’re not.

What is it to be twenty? Forty? Sixty? Eighty? These points that mark the four quarters of a life — fifths if you’re lucky, larger portions if you’re not.  1. The public library is holding a book or DVD for me.

1. The public library is holding a book or DVD for me.