by Nicola Sayers

What is it to be twenty? Forty? Sixty? Eighty? These points that mark the four quarters of a life — fifths if you’re lucky, larger portions if you’re not.

What is it to be twenty? Forty? Sixty? Eighty? These points that mark the four quarters of a life — fifths if you’re lucky, larger portions if you’re not.

*

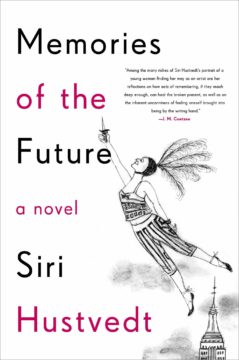

We read the book together, my mother and I. The book, a work of autofiction, is Siri Hustvedt’s Memories of the Future, and it tells the story of a twenty-three year old (S.H.) arriving in New York in 1978, and of the same woman in 2016, aged sixty-one, as she discovers her old journals from that earlier time. As we read, I am forty and my mother over seventy, although how much over I cannot say. I have learnt that there are those who treat you differently when they know your age, regardless of your health or vitality. That age is a signifier that in the end betrays you.

*

‘Then’ and ‘now’. Hustvedt draws attention to these words, these perspectives, again and again as she sets her reader up. Her central concern is with how a person changes between then and now; her central question, what remains of that girl?

*

The young S.H. could be any young, reflective woman setting out to soak up what the world has to offer. I admit to feeling a particular affinity with Hustvedt: Scandinavian roots, Jewish husband, PhD in literature before focussing on her own writing. But her story is in truth an archetypal one. She could be Felicity from the eponymous 90s TV-drama, going to New York in search of her crush Ben and of herself; or Jo from Little Women, heading off with pen and persistence to discover, write and right the world.

And so, I arrive in the city I have seen in films and have read about in books, which is New York City but also other cities, Paris and London and St. Petersburg, the city of the hero’s fortunes and misfortunes, a real city that is also an imaginary city.

I am reminded by Hustvedt’s prose of Joan Didion’s famous essay ‘Goodbye to all That’ about her experiences as a young person in New York, and about leaving it all behind. For both Hustvedt and Didion the defining experience of youth is of life as a field of possibility: Who will you meet? What will you do? Who will you love? What will you be?

I think of my own youth, some of it in New York. Of the many apartments, the many roommates, the many nights out which were also stories to tell. How central a seat the romantic agenda occupied in my emotional landscape. Countless hours spent analysing text messages from boys; every subway ride and book shop lent a frisson by the imagined prospect of meeting a handsome stranger. Once, I even wrote a Craigslist ‘missed encounter’ which read something like ‘cute guy I locked eyes with on the L’: a daydreamer’s modern-day missive, lobbed into the virtual sea to bob along in the fanciful dreamscape of romantics and perverts alike. I am reminded of the dizzying freedom of living in the realm of potential: potential encounters, potential discoveries, potential greatness.

At forty, my perspective on the young character is not that of the older character, reminiscing from far away. The young S.H. is still close, for me. I know all too well what it feels like to be her, I have been her for most of my life. But what grabs me — guts me, in moments — is that she is not that close anymore. My experience is no longer identical with hers: the young, thinking girl. And I don’t know when exactly that happened.

What I’m only really starting to understand now, which I didn’t then, is that as you rush along, chasing feelings, chasing dreams, you are in fact, often unwittingly, making choices. The lightness with which the young wear each next move is a trick of sorts, one played on the naive enthusiasts of the game called life (because to them it is, still, a game). Although each move — where to live, what to do, who to be with, how to dress, what principles to live by — remains in theory reversible, together they start to weave a pattern. And at some point, the scales weighing ‘possibility’ on one side and ‘actuality’ on the other tip.

I no longer contemplate psychoanalyst, lawyer or scuba-diving instructor as equally viable options that still lie ahead of me, but instead preoccupy myself with, say, a new writing idea. I do seriously think about moving to Berlin, but I think about it as a sabbatical, not an entirely new life to begin anew. And needless to say, while I continue to discover what love means in new and surprising ways with my husband, the end of the incessant search for romance has freed up an awful lot of energy for other things.

Then there are children. I’m wary of bringing the young mother’s perspective to bear as I don’t, even for a second, think that having a kid is the only or best path to a meaningful life. But I’m going to do it, briefly, because if we’re talking about the dance between actuality and possibility, a kid is perhaps the best example of something imagined in the abstract that becomes irreversibly tangible. It’s not just that a kid is — God willing — for life. It’s more that this kid, these kids, are the ones you got. I often think about this when I look at my two: my boy, his mischievous smile and love of sea creatures; my girl, her sincere face, which moves so readily between crossness and glee. You, little souls, are the ones that I got. Not the kid I might have wound up with at twenty with my first love. Not even the one I got pregnant with on our honeymoon, the one that we only knew about for five sweet days before that tiny life-spark peaced out, not long enough to count as a tragedy but enough to ponder from time to time. This endless field of possibility got narrowed down to two highly specific, all-fartingly all-screamingly actual beings. And it’s beautiful.

And yet.

If I am nostalgic these days — and sometimes I am — it is not for a specific time, place or person. It is for the sense of radical possibility that used to define the minutes and hours. I don’t think I am alone in this. It is a characteristic of my age group, or many among us. Deep in babies and homes and work and marriages, we pine for the time when we had no idea how our lives were going to turn out.

*

My mother says that the young S.H. feels far away for her. I still viscerally remember the specifics of my various apartments: the fire escape in Williamsburg that I used to sit and smoke on, the window in Tripoli that kept falling open in the middle of the night, the room with no windows in my sad London period. But for my mother — who is also a restless soul, and has lived many lives — the various apartments of her youth now meld into one. Small; charming; sites of many stairs and many hopes. (Many suitors, too, I imagine).

But I wonder how far away that young person really is. My mother has recently been bitten by an urge to buy a small flat in Oxford, where I now live. The reason, ostensibly, is to be near us, near her grandchildren. But watching her on her flat-hunt I see something else, too. She doesn’t look at sensible apartments, happy little granny-flats where the grandchildren might come and while away an afternoon. On the contrary, she is drawn to the quirkiest places. Crooked rooms at the top of winding stairwells otherwise occupied by graduate students of Russian or Theology, enchanted peony gardens down long paths, Juliet balconies that overlook the river. Apartments that might as well be in Paris, or Stockholm, or Amsterdam, the city of the hero’s fortunes and misfortunes, a real city that is also an imaginary city. In the temporary room she rents, she strikes up conversations with people about Pushkin, starts new reading groups with strangers. I see in her something that, for me, in these years of such immediate and often bodily demands, is harder to awaken. In some strange way it is at this juncture she, more than I, who is closer in spirit to the young S.H. She has circled back and is reaching out once again to grasp at the freedom of possibility.

*

It was impossible for me to know at twenty-three that the dreadful phrase “life is short” has meaning, that at sixty-one I know there is far less ahead of me than behind me

At forty, I am only now beginning to grasp the meaning of this well-worn phrase. I still hope to have more ahead of me than behind me — although how those dice fall is anyone’s guess — but I get it, now. Horrifyingly, I get it. I can’t remember who it was who talked about the distinction between ‘knowing about’ something, and knowing something — Rollo May? Paul Tillich? Kierkegaard? — but it strikes me as particularly pertinent here. At over seventy, my mother, of course, knows it too (although it sometimes occurs to me that early midlife is the closest you ever come to looking that truth in the eye; after that you do everything you can to forget it).

In many respects, the elder S.H., and my mother, are different to the young S.H. — to the young Felicity, the young Jo; to the young, thinking girl — but in none more so than this. And yet it is precisely this which makes my mother charging around in the realm of possibility that much better. The young wade around in possibility blithely, because they really do think that life will last forever. If the older can manage to touch it still — the sense of possibility, of the still not, the Not Yet — (and most don’t), it is defiant; brave; a final Fuck You to the Gods of inevitablity that has more genuine existential freedom to it than anything the young, with their lovers and flats and cities, can even begin to muster.