by Tim Sommers

Suppose on your way to work every day you pass a small, shallow pond. One day as you approach it, you hear a commotion and cries of “Help!” When you get close enough, you can see a small child is drowning in the pond. You could save them. The only problem is you are wearing new shoes for a big meeting today and they will get very muddy, probably ruined, if you save the child.

Should you save the child?

It seems like you should, right? At least, morally, you should. Peter Singer who came up with that example wanted to derive a very simple principle from it.

The Singer Principle: If it is in our power to prevent something very bad from happening, without sacrificing anything morally significant, we ought, morally, to do it.

What might be significant enough to make you hesitate to save the child? What if you might lose your job over it? And what if, when you lose your job, you and your family will quickly become homeless? What if the pond were deeper and you might drown yourself trying to save the kid?

Consider this.

You’re on your way to the movies. You’ve got your ticket money and your popcorn money. Let’s say $20. You run into an old friend of yours out front collecting money to save people from some far away catastrophe. You have complete faith and trust in her, so when she tells you that every $5 will save the life of one person, you believe her. And when she tells you that the catastrophe is likely short-lived and there’s no reason to think that anyone you save will die soon after. One life? $5. Two lives? $10. Do you give her anything? Your popcorn money? The whole $20? Do you go the ATM and withdrawal all you have? Would you be willing to remortgage your house? Read more »

Sughra Raza. Starry Night, October 2021.

Sughra Raza. Starry Night, October 2021.

The soon-to-be famous ship is part-way around the world. It will eventually become only the second vessel in recorded history to achieve the complete circumnavigation – after Magellan. But the ship is poised over disaster. Somewhere in the seas off present-day Indonesia, the captain has ordered full sail and then retired to his cabin. The ship hits something – there’s an awful shudder and it stops dead in the water. A reef, probably.

The soon-to-be famous ship is part-way around the world. It will eventually become only the second vessel in recorded history to achieve the complete circumnavigation – after Magellan. But the ship is poised over disaster. Somewhere in the seas off present-day Indonesia, the captain has ordered full sail and then retired to his cabin. The ship hits something – there’s an awful shudder and it stops dead in the water. A reef, probably.

Everyone knows—or should know—how burdensome a pregnancy is on a woman. It’s especially hard now if you live in Texas where a fetal heartbeat detected at six weeks means by law the woman cannot terminate her pregnancy; she must carry it to term. The burden of having a child, whether planned for or forced, is made worse by the financial responsibility of raising that offspring, for parents and families, through childhood and adolescence, the next eighteen years. Would any man argue that such a load, for poor women in particular, is among the toughest things she’ll ever face?

Everyone knows—or should know—how burdensome a pregnancy is on a woman. It’s especially hard now if you live in Texas where a fetal heartbeat detected at six weeks means by law the woman cannot terminate her pregnancy; she must carry it to term. The burden of having a child, whether planned for or forced, is made worse by the financial responsibility of raising that offspring, for parents and families, through childhood and adolescence, the next eighteen years. Would any man argue that such a load, for poor women in particular, is among the toughest things she’ll ever face? When Robert Solow asked me in Cambridge if I’d like to join the faculty at MIT in the other Cambridge, I was taken aback, and asked for some time to think about it. Until then I never imagined living in the US, a country I had never visited before, and what I saw in Hollywood films was not always attractive. I was planning to go back to India where my aging parents, younger siblings, and the majority of my friends were.

When Robert Solow asked me in Cambridge if I’d like to join the faculty at MIT in the other Cambridge, I was taken aback, and asked for some time to think about it. Until then I never imagined living in the US, a country I had never visited before, and what I saw in Hollywood films was not always attractive. I was planning to go back to India where my aging parents, younger siblings, and the majority of my friends were.

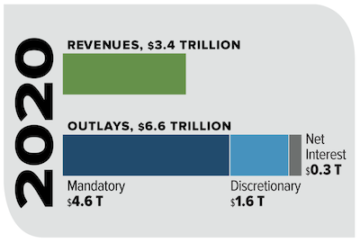

Someone described the US Federal Government as a huge insurance company that has its own army. There’s real truth to that description. The vast majority of the federal budget goes to Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid. Those entitlement programs take up about 65% of the federal budget, while the military takes up about 11% of the federal budget. The interest on the federal debt takes up another 8%, leaving only about 15% for “discretionary” spending. The money spent on the military is also considered discretionary but given our vast reach with hundreds of military bases in dozens of countries, voting to reduce the military budget much would be political suicide.

Someone described the US Federal Government as a huge insurance company that has its own army. There’s real truth to that description. The vast majority of the federal budget goes to Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid. Those entitlement programs take up about 65% of the federal budget, while the military takes up about 11% of the federal budget. The interest on the federal debt takes up another 8%, leaving only about 15% for “discretionary” spending. The money spent on the military is also considered discretionary but given our vast reach with hundreds of military bases in dozens of countries, voting to reduce the military budget much would be political suicide. Last year the federal government took in $3.4 trillion of taxes and spent $6.6 trillion, nearly twice its revenues. A trillion dollars is a vast, almost inconceivable amount of money. And yet our government spends money in such cosmic sums that congresspeople and senators toss around the word trillion as if it’s the cost of a night’s stay in a Motel 8. Perhaps the two best quotes about casually spending and losing vast sums of money come from the late Texas oilman Nelson Bunker Hunt. When asked about his $1.7 billion losses after he tried to corner the silver market, he replied, “A billion dollars isn’t what it used to be.” Then at a congressional hearing when asked about his net worth, Hunt replied, “I don’t have the figures in my head. People who know how much they’re worth aren’t usually worth that much.”

Last year the federal government took in $3.4 trillion of taxes and spent $6.6 trillion, nearly twice its revenues. A trillion dollars is a vast, almost inconceivable amount of money. And yet our government spends money in such cosmic sums that congresspeople and senators toss around the word trillion as if it’s the cost of a night’s stay in a Motel 8. Perhaps the two best quotes about casually spending and losing vast sums of money come from the late Texas oilman Nelson Bunker Hunt. When asked about his $1.7 billion losses after he tried to corner the silver market, he replied, “A billion dollars isn’t what it used to be.” Then at a congressional hearing when asked about his net worth, Hunt replied, “I don’t have the figures in my head. People who know how much they’re worth aren’t usually worth that much.”  Tanya Goel. Mechanisms 3, 2019.

Tanya Goel. Mechanisms 3, 2019.

Clairvoyant of the Small, Susan Bernofsky’s long-awaited biography of the Swiss modernist writer Robert Walser, is erudite, painstakingly thorough, and sensitively written. Readers of Walser finally have a volume that connects the development of the writer’s work and its publishing history to the various episodes of his peripatetic adult life in the cities of Biel, Bern, Zurich, Berlin, and finally the sanatoriums in Waldau and later Herisau, where Walser—revered by Franz Kafka and Max Brod, Walter Benjamin, W. G. Sebald, and many others—presumably ceased writing altogether.

Clairvoyant of the Small, Susan Bernofsky’s long-awaited biography of the Swiss modernist writer Robert Walser, is erudite, painstakingly thorough, and sensitively written. Readers of Walser finally have a volume that connects the development of the writer’s work and its publishing history to the various episodes of his peripatetic adult life in the cities of Biel, Bern, Zurich, Berlin, and finally the sanatoriums in Waldau and later Herisau, where Walser—revered by Franz Kafka and Max Brod, Walter Benjamin, W. G. Sebald, and many others—presumably ceased writing altogether.