by Mark Harvey

“I consider it completely unimportant who in the party vote, or how; but what is extraordinarily important is this–who will count the votes and how.” –Joseph Stalin

In the game of chess, there are dramatic moves such as when a knight puts the king in check while at the same time attacking the queen from the same square. Such a move is called a fork, and it’s always a delicious feeling to watch your opponent purse his lips and shake his head when you manage a good fork. The most dramatic move is obviously checkmate, when you capture the king, hide your delight, and put the pieces back in the box. But getting to either the fork or checkmate involves what’s known in chess as positioning, and for the masters, often involves quiet moves long in advance of the victory.

In the game of chess, there are dramatic moves such as when a knight puts the king in check while at the same time attacking the queen from the same square. Such a move is called a fork, and it’s always a delicious feeling to watch your opponent purse his lips and shake his head when you manage a good fork. The most dramatic move is obviously checkmate, when you capture the king, hide your delight, and put the pieces back in the box. But getting to either the fork or checkmate involves what’s known in chess as positioning, and for the masters, often involves quiet moves long in advance of the victory.

I wouldn’t compare Republican operators to a Garry Kasparov or Magnus Carlsen, but in several swing states that could determine the 2024 presidential elections, they are playing their own version of a quiet game and positioning to win the election by hook or by rook. As opposed to a Kasparov or a Carlsen, there’s nothing elegant about their strategy, and what they’re attempting to do is really an end-around any form of democracy. It involves the chess equivalent of mid-level pieces—bishops, knights, and even pawns–and in some cases, political positions you’ve probably never heard of.

The Republicans have taken a clinical look at the demographics, the voting trends, and the results of the 2020 election and concluded that a traditional play of just big money and ugly ads won’t do it next time. Yes, there will be a lot of ads with dark music, photoshopped images (using the darkening and contrast feature), and the menacing voice-over saying, “Candidate X wants to free all the criminals, raise your taxes to Venezuelan levels, and concede Texas to Russia.”

But to win in 2024, Republicans are working to change basic electoral rules, install vote counters and election judges, and make it much more difficult for those who would vote against their candidate to vote. You don’t have to be a grandmaster of politics to understand the plan and to see it happening in plain sight. But I fear that the average American voter, due to either the hazards of having a real life or lacking interest, is missing the beat. Read more »

From the gatherings at Ashis Nandy’s home, and particularly from my numerous discussions with him I learned to think a bit more carefully about three major social concerns in India.

From the gatherings at Ashis Nandy’s home, and particularly from my numerous discussions with him I learned to think a bit more carefully about three major social concerns in India. The philosopher Theodore Adorno, probably with activities such as reading serious literature and listening to classical music in mind, famously said about himself:

The philosopher Theodore Adorno, probably with activities such as reading serious literature and listening to classical music in mind, famously said about himself:

Sughra Raza. Bey Unvaan. Anza-Borrego Desert Park, Calfornia, 2017.

Sughra Raza. Bey Unvaan. Anza-Borrego Desert Park, Calfornia, 2017.

“Sewer designs… For me, it took about a year to exhaust my fascination with the underground maze of waste. That’s when I realized the single most important point to grasp about designing sewer lines is that the shit must flow downhill. That’s all one needs to know. Nothing else matters.” So muses Emma, a smart young sewer engineer and the protagonist of Sara Goudarzi’s debut novel The Almond in the Apricot. The book takes us through the convoluted maze of Emma’s own inner turmoil that begins to blur the boundaries between her physical world and her dreams.

“Sewer designs… For me, it took about a year to exhaust my fascination with the underground maze of waste. That’s when I realized the single most important point to grasp about designing sewer lines is that the shit must flow downhill. That’s all one needs to know. Nothing else matters.” So muses Emma, a smart young sewer engineer and the protagonist of Sara Goudarzi’s debut novel The Almond in the Apricot. The book takes us through the convoluted maze of Emma’s own inner turmoil that begins to blur the boundaries between her physical world and her dreams. When I am not doing well in my own head, I turn to the tarot. While no substitute for therapy or psychiatry, the tarot has an ancient function that is symbiotic with these modern methods for coping with the wild unruliness of the mind. I know it sounds silly. But before there was psychology and medicine, there was magic, and that is not silly at all. People crave rituals and symbols; they crave narratives about themselves with which to play and to experiment. And the tarot is nothing if not an arcane form of play and experimentation with the idea of the self, packed with ritual and narrative and symbol. Magic, you see, is a very minor thing. It does not make great things happen, and, when it is practiced honestly and forthrightly, it does not claim to make great things happen. Instead, magic is meant to open up little moments, little apertures into self-understanding, that allow for the flourishing of subjects in an otherwise mean and obscure world. It is difficult to be a subject in the world; it is a task with no guidebook and with few obvious parameters. Little practices that seek after the integration of the self with the world, that seek to make distinct and clear not only who the self is but what the self means and is capable of accomplishing and being with the materials of the world at hand—these kinds of practices, which include both the tarot and psychotherapy (the latter being perhaps a practice of magic in our modern lives), make it

When I am not doing well in my own head, I turn to the tarot. While no substitute for therapy or psychiatry, the tarot has an ancient function that is symbiotic with these modern methods for coping with the wild unruliness of the mind. I know it sounds silly. But before there was psychology and medicine, there was magic, and that is not silly at all. People crave rituals and symbols; they crave narratives about themselves with which to play and to experiment. And the tarot is nothing if not an arcane form of play and experimentation with the idea of the self, packed with ritual and narrative and symbol. Magic, you see, is a very minor thing. It does not make great things happen, and, when it is practiced honestly and forthrightly, it does not claim to make great things happen. Instead, magic is meant to open up little moments, little apertures into self-understanding, that allow for the flourishing of subjects in an otherwise mean and obscure world. It is difficult to be a subject in the world; it is a task with no guidebook and with few obvious parameters. Little practices that seek after the integration of the self with the world, that seek to make distinct and clear not only who the self is but what the self means and is capable of accomplishing and being with the materials of the world at hand—these kinds of practices, which include both the tarot and psychotherapy (the latter being perhaps a practice of magic in our modern lives), make it

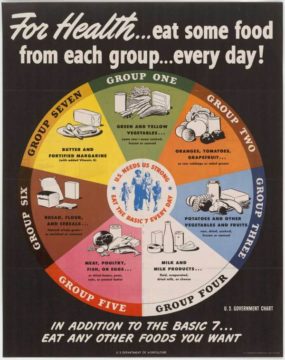

What to eat? A seemingly simple question, but one that has become increasingly difficult to answer. And why is that? My initial hypothesis is that as modern society becomes more and more distanced from traditional and local cuisines, people have less guidance as to what to eat; this puts increased pressure on individuals to make a conscious choice, but with unclear and often conflicting information about how to make this choice. In other words, people used to just eat whatever their grandparents had eaten, and this worked relatively well. Now, with an overabundance of choice and ignorance of one’s own past, we are lost, wandering through the supermarket aisles like a traveler lost in the woods. Thus, we see diets, meal plans, food delivery apps, and a myriad of other things jump in to fill the void that has been abdicated by family and community. But this story is perhaps so obvious that it does not need retelling. It is, after all, the story of the modern, global world. Nevertheless, it’s useful to pause, look around, and ask ourselves, “How did we get here? What is this place?” Let me sketch a few examples of people attempting to answer our initial question, “What to eat?” to help illustrate our general predicament.

What to eat? A seemingly simple question, but one that has become increasingly difficult to answer. And why is that? My initial hypothesis is that as modern society becomes more and more distanced from traditional and local cuisines, people have less guidance as to what to eat; this puts increased pressure on individuals to make a conscious choice, but with unclear and often conflicting information about how to make this choice. In other words, people used to just eat whatever their grandparents had eaten, and this worked relatively well. Now, with an overabundance of choice and ignorance of one’s own past, we are lost, wandering through the supermarket aisles like a traveler lost in the woods. Thus, we see diets, meal plans, food delivery apps, and a myriad of other things jump in to fill the void that has been abdicated by family and community. But this story is perhaps so obvious that it does not need retelling. It is, after all, the story of the modern, global world. Nevertheless, it’s useful to pause, look around, and ask ourselves, “How did we get here? What is this place?” Let me sketch a few examples of people attempting to answer our initial question, “What to eat?” to help illustrate our general predicament.