by Michael Abraham

Imagine a boy, and then call him Oliver. His eyes are olive, and this is why you will call him Oliver. Oliver is not his real name, but this is no matter. None of the names in a fable are real names. In a fable, characters are named things like Fox and Hare; they have names for reasons, to tell us what they are. Hence, we will name the boy Oliver because of his bright, olive eyes—his eyes which betray so much of the intensity of him.

Oliver has sparks inside him. Sometimes, Oliver thinks that he has these sparks inside him because he is a faggot; he believes, now and again, that faggots know more about the world than other people. He believes in what the scholar Jack Babuscio argues in a 1978 essay titled “Camp and the Gay Sensibility,” namely in “the gay sensibility as a creative energy reflecting a consciousness that is different from the mainstream; a heightened awareness of certain human complications of feeling that springs from the fact of social oppression; in short, a perception of the world which is coloured, shaped, directed, and defined by the fact of one’s gayness.” It is very certain that Oliver’s gayness is a spark inside of him, but Oliver has another spark inside of him, a wildness, a sparkling desire for the wideness and the depth of human experience. These twin sparks will inform and shape all of Oliver’s life, and, one day, that other spark will drive him mad. But, right now, Oliver is only sixteen, and the faggot spark is much brighter than the madness spark. Right now, Oliver is desperate for someone to love, for the overwhelm of another boy’s nakedness. In Autobiography of Red, Anne Carson writes that “Up against another human being one’s own procedures take on definition,” and though Oliver has not read Anne Carson yet, and though Oliver has limited experience with being up against another human being (a couple blowjobs, a couple kisses), Oliver intuits this already; intrinsically, Oliver knows that Oliver will not know himself until he is loved by another. It is in the midst of knowing this, in the midst of being quite troubled over it, that Oliver encounters Ezra. Read more »

“

“ In recent years the institution in England I have visited frequently is London School of Economics (LSE), in 1998 as a STICERD Distinguished Visitor, and in 2010-11 as a BP Centennial Professor (this was shortly after the disastrous BP oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico, so I hesitated telling people about my designation), and numerous times as visitor just for a few days. In recent times most of my interactions there have been with the development economists Tim Besley and Maitreesh Ghatak in the Economics Department and with Robert Wade, economist Jean-Paul Faguet and some years earlier, John Harriss (the political sociologist specializing in India) in the International Development Department. In recent years, apart from departmental seminars, I also gave two somewhat formal public lectures in a large LSE auditorium, once on China and India, and the other time on A New Agenda for Global Labor.

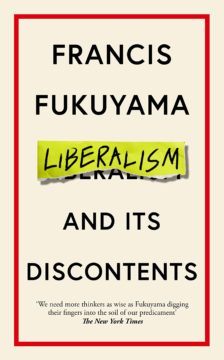

In recent years the institution in England I have visited frequently is London School of Economics (LSE), in 1998 as a STICERD Distinguished Visitor, and in 2010-11 as a BP Centennial Professor (this was shortly after the disastrous BP oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico, so I hesitated telling people about my designation), and numerous times as visitor just for a few days. In recent times most of my interactions there have been with the development economists Tim Besley and Maitreesh Ghatak in the Economics Department and with Robert Wade, economist Jean-Paul Faguet and some years earlier, John Harriss (the political sociologist specializing in India) in the International Development Department. In recent years, apart from departmental seminars, I also gave two somewhat formal public lectures in a large LSE auditorium, once on China and India, and the other time on A New Agenda for Global Labor. Francis Fukuyama does not mind having to play defense. Recognizing that the problems plaguing liberal societies result in no small part from the flaws and weaknesses of liberalism itself, he argues in Liberalism and its Discontents (Profile Books: 2022) that the response to these problems, all said and done, is liberalism. This requires some courage: three decades ago, Fukuyama may have captured the spirit of the age, but the spirit has grown impatient with liberalism as of late. Fukuyama, however, does not think of it as a worn-out ideal. He has taken note of right-wing assaults, as well as progressive criticisms that suggest a need to go beyond it; and his verdict is that any attempt at improvement will either stay in a liberal orbit or lead to political decay. Liberalism is still the best we have got.

Francis Fukuyama does not mind having to play defense. Recognizing that the problems plaguing liberal societies result in no small part from the flaws and weaknesses of liberalism itself, he argues in Liberalism and its Discontents (Profile Books: 2022) that the response to these problems, all said and done, is liberalism. This requires some courage: three decades ago, Fukuyama may have captured the spirit of the age, but the spirit has grown impatient with liberalism as of late. Fukuyama, however, does not think of it as a worn-out ideal. He has taken note of right-wing assaults, as well as progressive criticisms that suggest a need to go beyond it; and his verdict is that any attempt at improvement will either stay in a liberal orbit or lead to political decay. Liberalism is still the best we have got. Every now and then, a nation becomes modern. Greeks and Poles and Russians were modern, for a time. Now it’s the Ukrainians’ turn.

Every now and then, a nation becomes modern. Greeks and Poles and Russians were modern, for a time. Now it’s the Ukrainians’ turn. As the January 6th hearings continue and Americans watch

As the January 6th hearings continue and Americans watch  I knew it was coming, yet I was still surprised when it hit my classroom.

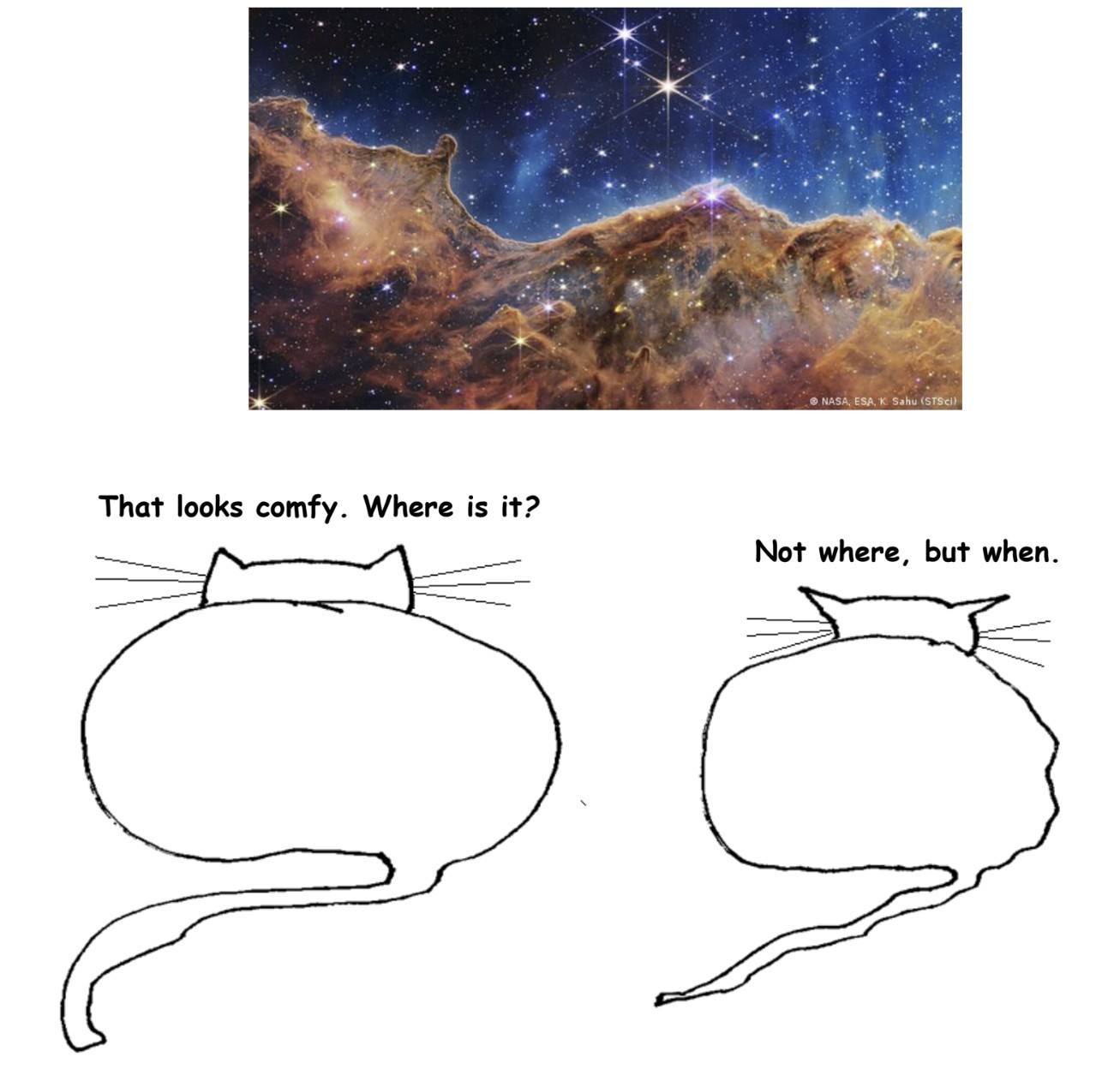

I knew it was coming, yet I was still surprised when it hit my classroom.  I think a lot about the fate of human civilization these days.

I think a lot about the fate of human civilization these days. Lorenza Böttner. Face Art, 1983.

Lorenza Böttner. Face Art, 1983.

Elections have consequences. Sometimes those consequences may be unintended, but they are always there. Elections have consequences. You can’t say it too many times because too many voters don’t act if they believe it. They should. Elections have consequences.

Elections have consequences. Sometimes those consequences may be unintended, but they are always there. Elections have consequences. You can’t say it too many times because too many voters don’t act if they believe it. They should. Elections have consequences.