by Brooks Riley

Of all the secondary discomforts imposed by the pandemic, the most treacherous may be inertia. Life, interrupted, can be characterized as an absence of movement, like a stream that stops running, stagnating as the surface begins to cloud with algae and other still-standing detritus. Inertia that stems from the current situation can quelch any creative impulse. Even cinema, that paradigm of life in motion—the moving picture—isn’t much help if we expect our own lives to keep moving as well as movies do. They don’t, at least not right now.

Of all the secondary discomforts imposed by the pandemic, the most treacherous may be inertia. Life, interrupted, can be characterized as an absence of movement, like a stream that stops running, stagnating as the surface begins to cloud with algae and other still-standing detritus. Inertia that stems from the current situation can quelch any creative impulse. Even cinema, that paradigm of life in motion—the moving picture—isn’t much help if we expect our own lives to keep moving as well as movies do. They don’t, at least not right now.

Now we sit at home and consume an ersatz elixir of motion on our streaming platforms, and without quite realizing it, get our kinetic gratification by surfing a narrative, instead of going out for a drive or a walk and seeing our visual field alter naturally.

Movement in this case is not about physical activity, or what we do, but rather about what we see, the perception of changing location in one or another direction—forward, out, away, off, back. On a walk, we may be thinking about our muscles, or about the surrounding nature. But we are mostly oblivious to the subtle changes in our field of vision as we move forward—that constant progress of our steps which alters the panorama ever so slightly. Seen this way, movement feeds our perceptions at the instinctual level. This is where the brain boards a train, metaphorically, to exercise its ability to adjust to change.

I miss trains. I miss the way the scene outside the window rapidly evolves as the miracle of speed presses ever new images on my retina. I miss the way my mind comes alive and cranks out thoughts and ideas at a similar speed. That there is a connection between what we see and what we think, even if none seems to exist, can be explained this way: Motion embodies two accelerators of thought, energy and change, both of which are in short supply if we’re locked down somewhere. The more sedentary and static our lives become the more we depend on the illusion of motion provided by second-hand sources. As the pandemic wears on, I find myself spending less time reading and more time on YouTube, not chasing stories to get lost in, but seeking some kind of eye candy that moves.

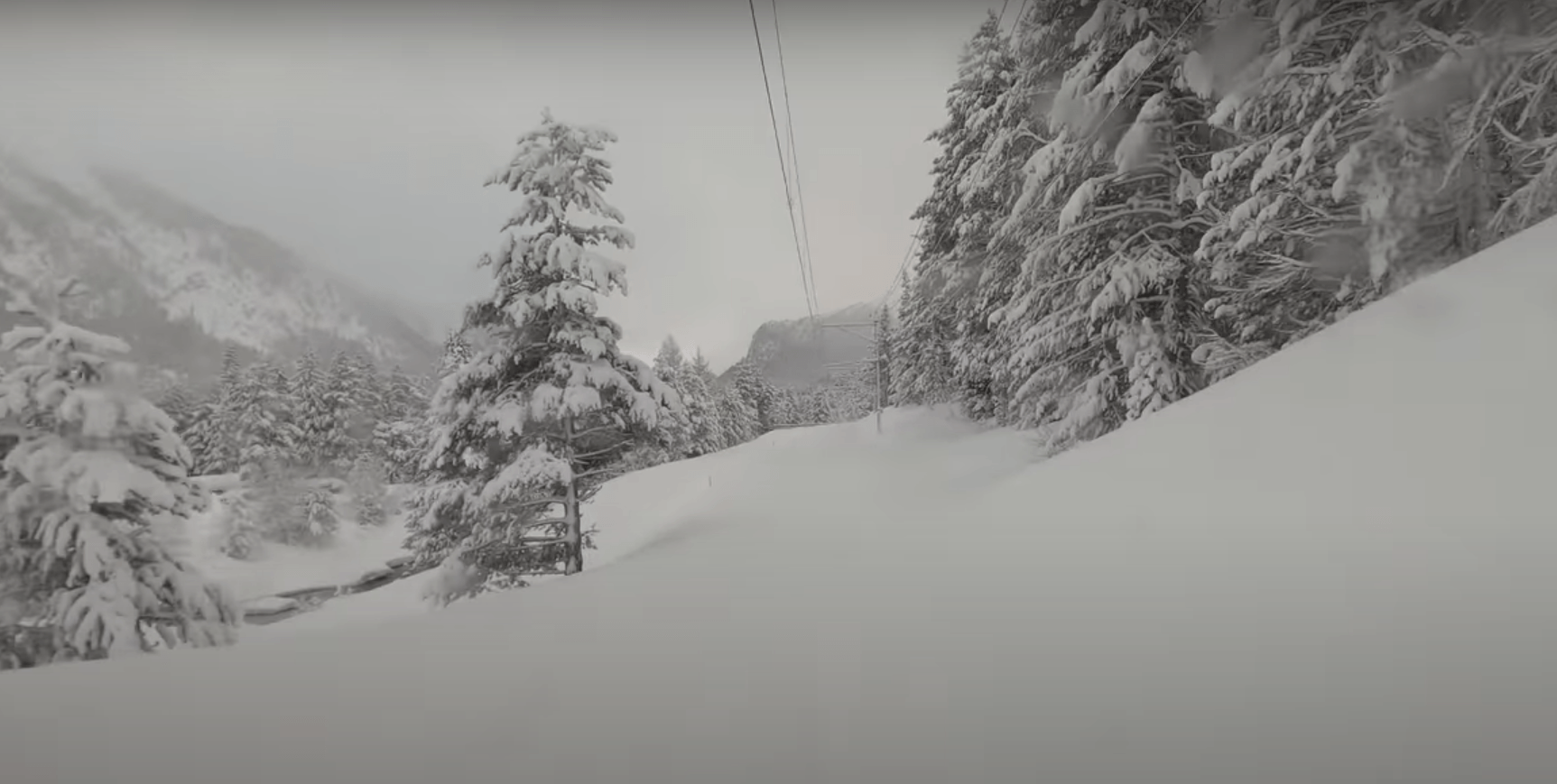

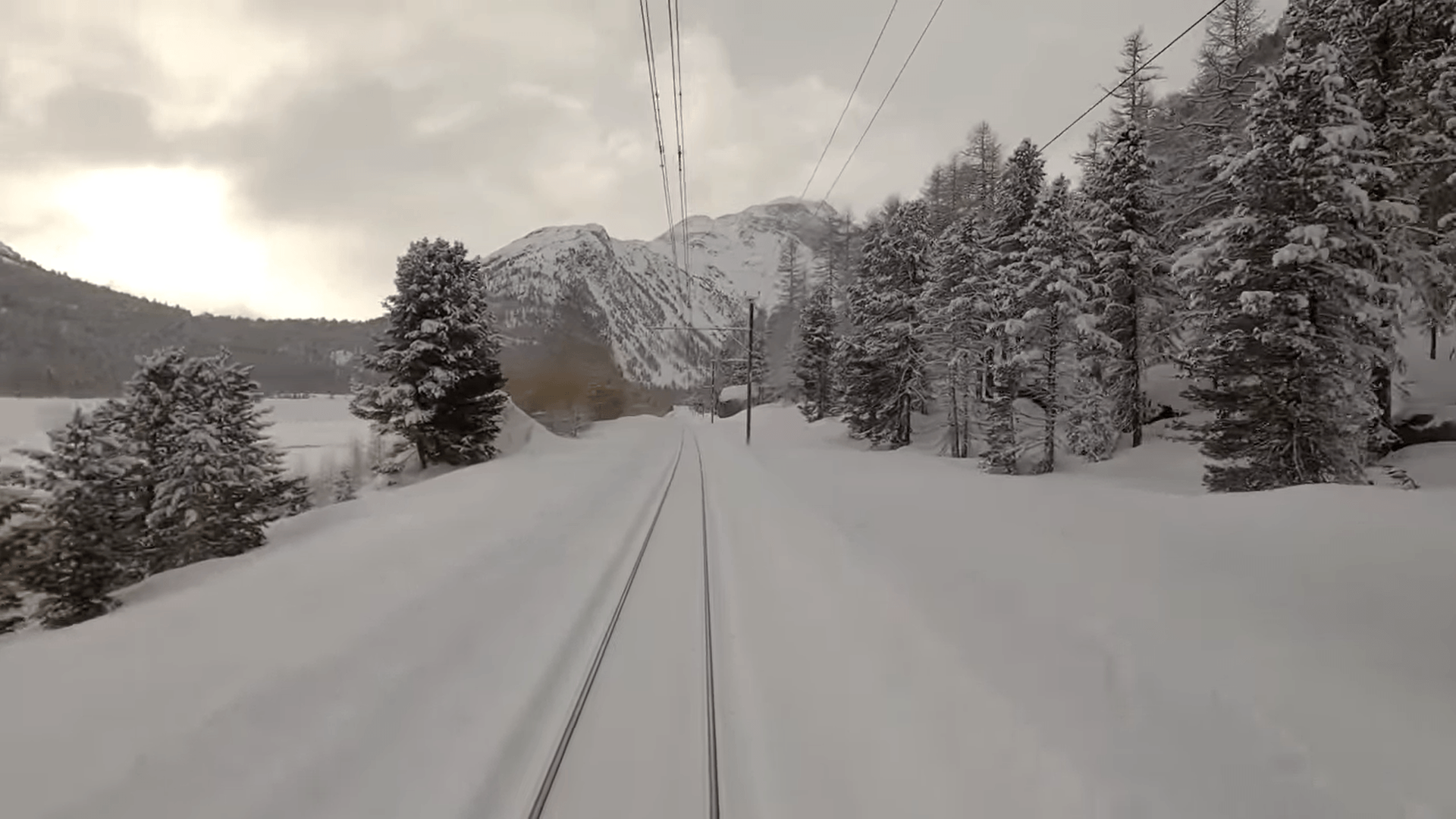

I’ve found it on the YouTube channel lorirocks777, featuring the historic Swiss Bernina railroad line. This 4K treasure trove of videos includes a number of runs between St. Moritz and Tirano, Italy, showcasing all kinds of weather and topography. At 60 frames* per second, these journeys simulate reality so well that the mind/movement effect remains intact. Even better, the ride is not one-sided, as it would be from a passenger’s point of view. This is the full frontal, 180-degree moveable feast that the train driver sees, with a perspective point straight ahead. The suspense of moving around a curve into the unknown is magically intensified when the track itself disappears under a snow drift. Plowing over viaducts is equally vertigo-inducing, even with the welcome assurance that one is safely ensconced at home in one’s chair.

There are several ways to experience this journey: The sounds of the train are surprisingly unobtrusive, even comforting. This is a smooth ride, not the Amtrak lurches of distant memory. Without sound, the ride takes on an other-worldly quality, as though one were floating through the landscape instead of firmly attached to a track. This is especially powerful during the snow drifts, when no evidence of the train or its tracks are visible.

The train driver (often Paolo, his name discreetly burned into the image at departure) provides the names of every tunnel (there are 55 along this route) and every bridge or viaduct (196), adding the year they were built. This is where I begin to leave the reality in front of me and wander back to the year after my mother was born—she in her cradle, thousands of miles away from the many nameless workers who risked life and limb to bore a hole in this mountain that same year. I find myself mourning these unknowns out of gratitude. In the tunnels, I can almost see their faces turned toward the light of the approaching train. Thanks to them, I can go from St. Moritz to Tirano as if I were walking through walls.

Train trips always awaken my nesting instinct. I don’t want to just visit places; I want to live in them, no matter how remote—call me a serial nester, even if lack the funds to establish pieds-à-terre everywhere. On the way to Tirano, I see myself living in that small chalet beside the railroad tracks, waving to Paolo from the balcony, or murmuring in my sleep to the click-clack of train wheels at night.

Unable to resist the temptation to interact with these videos, I have begun to score them from a Spotify playlist, starting with Richard Strauss’s Alpine Symphony, a rather obvious choice that didn’t quite deliver the emotional charge I expected. Although I plan to continue experimenting, a run with Strauss’s Metamorphosen was surprisingly emotional, especially as the train navigated the scattered pines along the route and approached what looked like better weather ahead.

Metamorphosen has been in the spotlight of late, a quasi pandemic theme song, elegiac but at the same time strangely hopeful. The Berlin Philharmonic performed it in February. Last week, it was the first performance by the New York Philharmonic since the pandemic began. Given that we’ve all been somehow transformed by the Covid disaster, it’s a fitting choice. This piece resonates for me because Strauss, who was 80 at the time, began composing it during the month of my birth–probably sitting at a table with a view of the Alps. As I was undergoing my own metamorphosis from fetus to infant, much of the world was facing death and destruction on a massive scale—a juxtaposition that has haunted me for decades. Although Strauss never explained this ‘study for 23 solo strings’ the fact that he used the plural of metamorphosis suggests a multitude of transformations both past and future, both personal and global, that were and would be tragic or redemptive. Abstaining from his often bombastic orchestral style, Strauss contemplates the remnants of possibility even as he mourns the great losses, reflecting the eternal duality of death and transfiguration. Even after the pandemic ends, we will have to confront climate’s ongoing metamorphosis with metamorphoses of our own.

If there is something beyond the sheer hypnotic pleasure of these railway daytrips, it’s their metaphoric weight, fulfilling first and foremost the promise that we are moving forward and getting somewhere. Forward motion has never seemed more effortless or more necessary–a healthy antidote to uncertainty, stagnation, depression. Even the weather plays along. The train departs in a snowstorm, but before long a patch of brightness can be seen on the horizon. What more could we ask for during the winter of our discontent?

***

*The first 60 fps film I ever saw also involved snow. In the early Eighties Douglas Trumbull showed off his new HD film system Showscan at a small screening. Using 70mm film shot at 60 fps, the short demonstration film of skiing made me nauseated. No one seemed to know why. The screen was huge, and the snow of a brightness I had never encountered in a movie before—the unbearable whiteness of seeing.

Suggested links:

a short film about the Bernina Express rail line

Earlier posts featuring trains here and here

An automobile version of forward motion, from Austria to Slovenia to Italy.