by Timothy Don

The current economic crisis is crushing artists, museums, and galleries everywhere. In the San Francisco Bay Area, where I live, an exorbitant rental market made maintaining a practice difficult before this crisis hit. It’s even harder now. With 3QD’s permission, I’m going to use this column to talk about the work of some of the artists and art professionals I have met here. I ask you to support artists wherever and however you can.

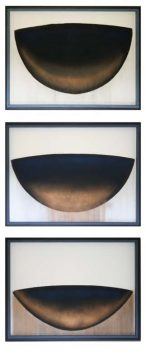

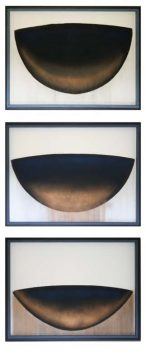

Peter de Swart, works on paper: Triptych

The triptych form is associated with religious painting. It first appeared as a feature of early Christian art and became popular for altar paintings and devotionals during the Middle Ages. While Peter de Swart’s Triptych is not overtly religious, it emanates an undeniably religious or spiritual aura. It is, in a word, numinous. To encounter this painting is to witness a sacred transaction. You’d have to be a stone to look at it and not experience a yearning for the divine. Why, apart from its rearticulation of the history and symbolism of the triptych form, is that?

It must have something to do, first of all, with the simple purity of the object pictured, which appears to be a bowl of some sort. Bowls are one of those inventions (like scissors or chopsticks or the hourglass) that we got right the first time. They were perfect the moment they appeared. In the bowl, function lives harmoniously with form. Its shape is so ideal as to be almost Platonic. Furthermore, bowls are used to prepare and serve food and drink, which means that they give sustenance, enable shared meals, and consequently help to strengthen communal bonds and deepen human relationships. Finally, bowls are vessels. Like hands and pockets and ships, they hold and contain and convey things—but they are not grasping like hands, nor like pockets do they secret away their contents, and they don’t trade goods and gold like ships. Quite the opposite, in fact: Bowls are generous, open, gratuitous. They give away the things they hold.

All of these attributes (form, use value, ethos) lend bowls a quasi-spiritual redolence, but they do not make bowls sacred. If this triptych depicted a bowl no different from any other bowl, then its effect would be decorative rather than numinous. This bowl is special. Again we must ask: Why is that? Read more »

Wine and music pairing is becoming increasingly popular, and the effectiveness of using music to enhance a wine tasting experience has received substantial empirical confirmation. (I summarized this data and the aesthetic significance of wine and music pairing last month on this site.) But to my knowledge there is no guide to how one should go about wine and music pairing. Are there pairing rules similar to the rules for pairing food and wine? Is there expertise involved that requires practice and experience?

Wine and music pairing is becoming increasingly popular, and the effectiveness of using music to enhance a wine tasting experience has received substantial empirical confirmation. (I summarized this data and the aesthetic significance of wine and music pairing last month on this site.) But to my knowledge there is no guide to how one should go about wine and music pairing. Are there pairing rules similar to the rules for pairing food and wine? Is there expertise involved that requires practice and experience?

For many wine lovers, understanding wine is hard work. We study maps of wine regions and their climates, learn about grape varietals and their characteristics, and delve into various techniques for making wine, trying to understand their influence on the final product. Then we learn a complex but arcane vocabulary for describing what we’re tasting and go to the trouble of decanting, choosing the right glass, and organizing a tasting procedure, all before getting down to the business of tasting. This business of tasting is also difficult. We sip, swish, and spit trying to extract every nuance of the wine and then puzzle over the whys and wherefores, all while comparing what we drink to other similar wines. Some of us even take copious notes to help us remember, for future reference, what this tasting experience was like.

For many wine lovers, understanding wine is hard work. We study maps of wine regions and their climates, learn about grape varietals and their characteristics, and delve into various techniques for making wine, trying to understand their influence on the final product. Then we learn a complex but arcane vocabulary for describing what we’re tasting and go to the trouble of decanting, choosing the right glass, and organizing a tasting procedure, all before getting down to the business of tasting. This business of tasting is also difficult. We sip, swish, and spit trying to extract every nuance of the wine and then puzzle over the whys and wherefores, all while comparing what we drink to other similar wines. Some of us even take copious notes to help us remember, for future reference, what this tasting experience was like. Epistenology: Wine as Experience

Epistenology: Wine as Experience Philosophy has been an ongoing enterprise for at least 2500 years in what we now call the West and has even more ancient roots in Asia. But until the mid-2000’s you would never have encountered something called “the philosophy of wine.” Over the past 15 years there have been several monographs and a few anthologies devoted to the topic, although it is hardly a central topic in philosophy. About such a discourse, one might legitimately ask why philosophers should be discussing wine at all, and why anyone interested in wine should pay heed to what philosophers have to say.

Philosophy has been an ongoing enterprise for at least 2500 years in what we now call the West and has even more ancient roots in Asia. But until the mid-2000’s you would never have encountered something called “the philosophy of wine.” Over the past 15 years there have been several monographs and a few anthologies devoted to the topic, although it is hardly a central topic in philosophy. About such a discourse, one might legitimately ask why philosophers should be discussing wine at all, and why anyone interested in wine should pay heed to what philosophers have to say. What did the wines that stimulated conversation in Plato’s Symposium taste like? Or the clam chowder in Moby Dick, or the “brown and yellow meats” served to Mr. Banks in To the Lighthouse? Or consider this repast from Joyce’s Ulysses:

What did the wines that stimulated conversation in Plato’s Symposium taste like? Or the clam chowder in Moby Dick, or the “brown and yellow meats” served to Mr. Banks in To the Lighthouse? Or consider this repast from Joyce’s Ulysses: A life in which the pleasures of food and drink are not important is missing a crucial dimension of a good life. Food and drink are a constant presence in our lives. They can be a constant source of pleasure if we nurture our connection to them and don’t take them for granted.

A life in which the pleasures of food and drink are not important is missing a crucial dimension of a good life. Food and drink are a constant presence in our lives. They can be a constant source of pleasure if we nurture our connection to them and don’t take them for granted. I often hear it said that, despite all the stories about family and cultural traditions, winemaking ideologies, and paeans to terroir, what matters is what’s in the glass. If a wine has flavor it’s good. Nothing else matters. And, of course, the whole idea of wine scores reflects the idea that there is single scale of deliciousness that defines wine quality.

I often hear it said that, despite all the stories about family and cultural traditions, winemaking ideologies, and paeans to terroir, what matters is what’s in the glass. If a wine has flavor it’s good. Nothing else matters. And, of course, the whole idea of wine scores reflects the idea that there is single scale of deliciousness that defines wine quality. Beauty has long been associated with moments in life that cannot easily be spoken of—what is often called “the ineffable”. When astonished or transfixed by nature, a work or art, or a bottle of wine, words even when finely voiced seem inadequate. Are words destined to fail? Can we not share anything of the experience of beauty? On the one hand, the experience of beauty is private; it is after all my experience not someone else’s. But, on the other hand, we seem to have a great need to share our experiences. Words fail but that doesn’t get us to shut up.

Beauty has long been associated with moments in life that cannot easily be spoken of—what is often called “the ineffable”. When astonished or transfixed by nature, a work or art, or a bottle of wine, words even when finely voiced seem inadequate. Are words destined to fail? Can we not share anything of the experience of beauty? On the one hand, the experience of beauty is private; it is after all my experience not someone else’s. But, on the other hand, we seem to have a great need to share our experiences. Words fail but that doesn’t get us to shut up.

In discourse about wine, we do not have a term that both denotes the highest quality level and indicates what that quality is that such wines possess. We often call wines “great”. But “great” refers to impact, not to the intrinsic qualities of the wine. Great wines are great because they are prestigious or highly successful—Screaming Eagle, Sassicaia, Chateau Margaux, Penfolds Grange, etc. They are made great by their celebrity, but the term doesn’t tell us what quality or qualities the wine exhibits in virtue of which they deserve their greatness. Sometimes the word “great” is just one among many generic terms—delicious, extraordinary, gorgeous, superb—we use to designate a wine that is really, really good. But these are vacuous, interchangeable and largely uninformative.

In discourse about wine, we do not have a term that both denotes the highest quality level and indicates what that quality is that such wines possess. We often call wines “great”. But “great” refers to impact, not to the intrinsic qualities of the wine. Great wines are great because they are prestigious or highly successful—Screaming Eagle, Sassicaia, Chateau Margaux, Penfolds Grange, etc. They are made great by their celebrity, but the term doesn’t tell us what quality or qualities the wine exhibits in virtue of which they deserve their greatness. Sometimes the word “great” is just one among many generic terms—delicious, extraordinary, gorgeous, superb—we use to designate a wine that is really, really good. But these are vacuous, interchangeable and largely uninformative. Research by linguists

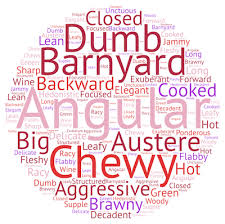

Research by linguists The wine community is often accused of being snobby and elitist. The language used to describe wine is one source of this innuendo. Although most people have become accustomed to the fruit descriptors used in wine reviews, when wine writers wax poetic by describing wines as “graphite mixed with pâte de fruit”, even

The wine community is often accused of being snobby and elitist. The language used to describe wine is one source of this innuendo. Although most people have become accustomed to the fruit descriptors used in wine reviews, when wine writers wax poetic by describing wines as “graphite mixed with pâte de fruit”, even  Wine writers, especially those who write wine reviews, are often derided for the flowery, overly imaginative language they use to describe wines. Some of the complainants are consumers baffled by what descriptors such as “brooding” or “flamboyant” might mean. Other complainants are experts who wish wine language had the precision of scientific discourse. The Journal of Wine Economists

Wine writers, especially those who write wine reviews, are often derided for the flowery, overly imaginative language they use to describe wines. Some of the complainants are consumers baffled by what descriptors such as “brooding” or “flamboyant” might mean. Other complainants are experts who wish wine language had the precision of scientific discourse. The Journal of Wine Economists  Wine is a living, dynamically changing, energetic organism. Although it doesn’t quite satisfy strict biological criteria for life, wine exhibits constant, unpredictable variation. It has a developmental trajectory of its own that resists human intentions and an internal structure that facilitates exchange with the external environment thus maintaining a process similar to homeostasis. Organisms are disposed to respond to changes in the environment in ways that do not threaten their integrity. Winemakers build this capacity for vitality in the wines they make.

Wine is a living, dynamically changing, energetic organism. Although it doesn’t quite satisfy strict biological criteria for life, wine exhibits constant, unpredictable variation. It has a developmental trajectory of its own that resists human intentions and an internal structure that facilitates exchange with the external environment thus maintaining a process similar to homeostasis. Organisms are disposed to respond to changes in the environment in ways that do not threaten their integrity. Winemakers build this capacity for vitality in the wines they make. Among the best books I’ve read about wine are the two by wine importer Terry Theise.

Among the best books I’ve read about wine are the two by wine importer Terry Theise.  It’s fashionable to criticize wine critics for a variety of sins: they’re biased, their scores don’t mean anything, and their jargon is unintelligible according to the critics of critics. Shouldn’t we just drink what we like? Who cares what critics think? In fact, whether the object is literature, painting, film, music, or wine, criticism is important for establishing evaluative standards and maintaining a dialogue about what is worth experiencing and why. The following is an account of how wine criticism aids wine appreciation by way of providing an account of wine appreciation.

It’s fashionable to criticize wine critics for a variety of sins: they’re biased, their scores don’t mean anything, and their jargon is unintelligible according to the critics of critics. Shouldn’t we just drink what we like? Who cares what critics think? In fact, whether the object is literature, painting, film, music, or wine, criticism is important for establishing evaluative standards and maintaining a dialogue about what is worth experiencing and why. The following is an account of how wine criticism aids wine appreciation by way of providing an account of wine appreciation. Why do we value successful art works, symphonies, and good bottles of wine? One answer is that they give us an experience that lesser works or merely useful objects cannot provide—an aesthetic experience. But how does an aesthetic experience differ from an ordinary experience? This is one of the central questions in philosophical aesthetics but one that has resisted a clear answer. Although we are all familiar with paradigm cases of aesthetic experience—being overwhelmed by beauty, music that thrills, waves of delight provoked by dialogue in a play, a wine that inspires awe—attempts to precisely define “aesthetic experience” by showing what all such experiences have in common have been less than successful.

Why do we value successful art works, symphonies, and good bottles of wine? One answer is that they give us an experience that lesser works or merely useful objects cannot provide—an aesthetic experience. But how does an aesthetic experience differ from an ordinary experience? This is one of the central questions in philosophical aesthetics but one that has resisted a clear answer. Although we are all familiar with paradigm cases of aesthetic experience—being overwhelmed by beauty, music that thrills, waves of delight provoked by dialogue in a play, a wine that inspires awe—attempts to precisely define “aesthetic experience” by showing what all such experiences have in common have been less than successful. If a rectangular canvas splashed with paint and lines can express freedom or joy, why not liquid poetry?

If a rectangular canvas splashed with paint and lines can express freedom or joy, why not liquid poetry? In giving an account of the aesthetic value of wine, the most important factor to keep in mind is that wine is an everyday affair. It is consumed by people in the course of their daily lives, and wine’s peculiar value and allure is that it infuses everyday life with an aura of mystery and consummate beauty. Wine is a “useless” passion that has a mysterious ability to gather people and create community. It serves no other purpose than to command us to slow down, take time, focus on the moment, and recognize that some things in life have intrinsic value. But it does so in situ where we live and play. Wine transforms the commonplace, providing a glimpse of the sacred in the profane. Wine’s appeal must be understood within that frame.

In giving an account of the aesthetic value of wine, the most important factor to keep in mind is that wine is an everyday affair. It is consumed by people in the course of their daily lives, and wine’s peculiar value and allure is that it infuses everyday life with an aura of mystery and consummate beauty. Wine is a “useless” passion that has a mysterious ability to gather people and create community. It serves no other purpose than to command us to slow down, take time, focus on the moment, and recognize that some things in life have intrinsic value. But it does so in situ where we live and play. Wine transforms the commonplace, providing a glimpse of the sacred in the profane. Wine’s appeal must be understood within that frame. Wine writers often observe that wine lovers today live in a world of unprecedented quality. What they usually mean by such claims is that advances in wine science and technology have made it possible to mass produce clean, consistent, flavorful wines at reasonable prices without the shoddy production practices and sharp bottle or vintage variations of the past.

Wine writers often observe that wine lovers today live in a world of unprecedented quality. What they usually mean by such claims is that advances in wine science and technology have made it possible to mass produce clean, consistent, flavorful wines at reasonable prices without the shoddy production practices and sharp bottle or vintage variations of the past.